Reading the Old Testament

The Value and Relevance of the Old Testament

Religion has come under fire in recent years. Many believe that science has explained so much that religion is now redundant. Humanity has “matured,” and religion is a cultural artifact. The new atheists go even further and aver that the monotheistic religions in particular promote ignorance, bigotry, and violence. Indeed, radical fundamentalism, particularly in the Middle East, has taken that violence to new levels of terror and horror. And, closer to home, evangelical Christianity has become a bargaining chip in American politics.

“Faith is permitting ourselves to be seized by the things we do not see."

Martin Luther

Nevertheless, religion maintains a dogged persistence and remains relevant because humans still ask the big questions. Science is the principal tool for answering questions of “How?” and to some extent questions of “What?” But the questions of “Why?” and the “What?” questions pertaining to human identity are fundamentally religious in nature.

There remains the nagging suspicion that a mere materialist universe is reductionist—a view that dismisses the possibility of the Transcendent out of hand. Although religion is about God, it also asks questions that are fundamental to our humanity. Am I a remarkable accident: the result of physics, chemistry, and biology? Does my life have meaning, purpose, … a destiny? Is there existence beyond mortality?

Believers, agnostics, and atheists must all agree that the Bible has informed Western culture. Much of Western literature cannot be explained apart from it. Biblical idioms have become so much a part of everyday speech that most of us are not even aware that we quote the Bible (e.g., “by the skin of your teeth,” Job 19:20; “a fly in the ointment,” Eccl 10:1; “a drop in a bucket,” Isaiah 40:15; “the writing is on the wall,” Dan 5).

Science has thrived in the West largely because the Bible has demythologized the universe, separating God and his creation, thereby making natural law conceivable. Our legal systems are indebted to the Ten Commandments and the Bible’s value of justice. The Bible, rightly or wrongly, has informed the Western conscience: morality, the sense of guilt (as distinct from shame), and the recompense of heaven and hell. To understand ourselves—whether religious or not—we need to evaluate and assess the Bible.

Even before the invention of Gutenberg’s printing press, the Bible has long been the world’s best seller. Christians rightly celebrate its success. But familiarity breeds assumptions. For many Christians, our received traditions are like the air we breathe: we take them in and give them out without conscious deliberation. We may give little reflective thought to their continuing validity and to other perspectives. The Bible has become a cultural icon in the West, so it can be difficult to distinguish what is indeed biblical and what has become simply a cultural norm. Are we able to discern the difference between faith and ideology? Christians have invoked the Bible for authoritative statements, whether denominational or political, yet how many have actually read it, let alone studied it?

A university course on the Bible is the opportune moment for students to have their horizons opened and to reflect on their prior knowledge and beliefs. The tools of the university have advanced human knowledge, including our knowledge of the Bible.

Indeed, the academic field of biblical studies represents the essence of liberal arts education, especially in the humanities. The student of the Bible will be trained as part linguist, literary critic, archaeologist, historian, sociologist, philosopher, and rhetorician—skills that can be transferred to any major or career path.

What happens at university, as distinct from Sunday school, is critical research—critical, not in the sense of a faultfinding or disparaging attitude, but in the sense of discernment. This sense can be illustrated from the Hebrew language. The verb translated, “to understand” (בִּין, bîn), and the noun, “understanding” (בִּינָה, bînah), are etymologically related to the preposition translated, “between” (בֵּין, bên). In this respect, the essence of understanding is discernment: being able to distinguish between two objects or actions.

At times, this will involve distinguishing between what one was taught in Sunday school from what the Hebrew Bible actually claims. Hence, for those readers who regard the Bible as inspired and authoritative and are thus heavily invested in what they think the Bible says, such an endeavor can be threatening. Courage may be a necessary prerequisite. The journey at times may seem complicated and confusing but by the end of the course it is hoped that the student’s perspective on the Bible will be richer, deeper, and more grounded.

One could also mount a cogent argument that the study of the Bible should be a “course requirement” for anyone. As it raises fundamental questions about what it means to be human and especially because it has so imbued Western culture and thinking, the Bible should, at the very least, be one’s familiar conversation partner. The Bible can serve as a mirror for understanding our individual selves (our values and sense of worth, our guilt and our redemption), our neighbors and those who are different from us, and our beliefs about God and eternity.

A Historical Survey of the Old Testament

In the charts below some dates are approximate or rounded off for the student's convenience.

Date Period: Events and Figures (Biblical Books)

2000 Ancestral: Abraham, Isaac, Jacob/Israel, Joseph (Gen 12–50)

1200s Mosaic: exodus, Sinai, wilderness (Exod, Num)

Conquest//Settlement: Joshua (Josh, Judg 1)

Judges: Deborah, Gideon, Samson, Samuel (Judg–1 Sam 8, Ruth)

1000 United Monarchic: Saul, David, Solomon (1 Sam–1 Kgs 11)

922 Divided Monarchic: (northern) Israel and Judah (1 Kgs 12–2 Kgs 17)

722 Exile of Israel by Assyria (2 Kgs 17). Judah alone (2 Kgs 18–25)

622 Josiah’s Reform: publication of Deut (2 Kgs 22–23)

597 First deportation of Judah to Babylon (2 Kgs 24)

587 Exilic: fall of Jerusalem and second deportation (2 Kgs 25)

538 Postexilic: Persian Decree: return of Jews to homeland (2 Chr 36:22-23)

515 Second Temple rebuilt (Ezra 3–6)

458? Returns under Ezra and Nehemiah (445?) (Ezra, Neh)

Ezra reads "the Book of the Law of Moses" (Neh 8:1-3, 8)

Prophetic Books: Northern Kingdom

Century,

Empire Prophet (issues; traditions)

mid-8th Amos (social injustice, religious hypocrisy; exodus)

Assyria Hosea (religious adultery to Baal; exodus, covenant, torah)

722 (Exile of Israel by Assyria)

Prophetic Books: Judah

late-8th Isaiah 1-39 (social injustice, political alliances; David, Zion)

Micah (idolatry, social injustice, Yahweh’s case; David, Zion)

late-7th Zephaniah (“Day of Yahweh”)

Nahum (doom for cruel Nineveh)

Babylon Habakkuk (dialogue: judgment thru and upon the Babylonians)

Jeremiah (idolatry, false trust in temple, judgment thru Babylon; new covenant)

early-6th Ezekiel (Yahweh’s Glory departs and later returns to new temple)

587 (Exile of Judah by Babylon)

Obadiah (Edom to be ransacked because of inhumanity to Judah)

mid-6th Isa 40-55 (Cyrus, second exodus, new Jerusalem)

Persia

538 (Return/Restoration of Judah)

late-6th Isa 56-66 (glorious Zion delayed because of sin)

Haggai (rebuilding the temple)

Zechariah (rebuilding the temple, messianic kingdom)

Joel (locust plague, Spirit poured out)

mid-5th Malachi (lame sacrifices, no tithes, Yahweh’s coming Day)

Inner-biblical Interpretation as a Model for Proper Interpretation

► §3.3.1. How the Bible uses the Bible is more telling than what isolated verses appear to say about the Bible.

What is the Bible and how is it meant to be used? This question has always been fundamental for Jews and Christians alike. But a deliberate answer is now all the more necessary in view of how religious devotees—whether Jewish Christian, or Muslim—have invoked their scriptures to justify all kinds of violence and exclusion. The most common point of departure has been to consider passages that appear to explicitly address the question of the Bible’s nature and authority—especially as the Word of God (e.g., 2 Tim 3:16; Matt 5:18; cf. 1:22; 4:4). But after closer examination, we discover that, while they shed light on the general character of the Bible, they do not yield many specific guidelines for interpretation. More revealing are passages that actually use earlier biblical passages. What the Bible says about itself is one thing, but what it actually does with other biblical material is quite another. Each must qualify the other, as inductive reasoning must complement deductive reasoning. How the Bible uses the Bible must qualify what the Bible says about the Bible. We will consider what the Bible explicitly claims about itself, but these claims are often stated in general terms that are often misconstrued. What is more indicative is how later portions of the Bible interpret and use earlier portions.

The book of Deuteronomy is a particularly instructive example of how the biblical canon is meant to work. Twice it insists:

You must neither add anything to what I command you nor take away anything from it, but keep the commandments of the Lord your God with which I am charging you. (Deut 4:2, NRSV)

You must diligently observe everything that I command you; do not add to it or take anything from it. (Deut 12:32, NRSV)

Isolated verses may appear to suggest an unalterable text and a closed canon, but Deuteronomy, as a second law, radically reinterprets and revises laws found in the earlier "Book of the Covenant" in Exodus 20-23.

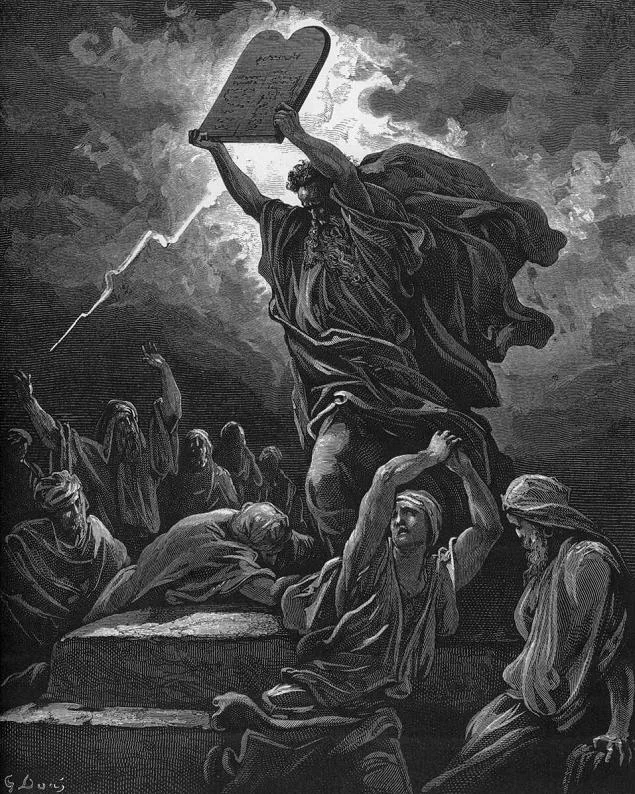

Moses holding the Ten Commandments. Drawing: Gustave Dore

Taken at face value, these injunctions appear to indicate a notion of an unalterable text and a closed canon. For Christians, the book of Revelation closes with a similar admonition (Rev 22:18–19). Indeed, one can imagine using these verses as prooftexts for a doctrine about the Bible. Yet, ironically, the book of Deutero-nomy, as its name implies, is itself a second presentation of law. This “Book of the Law” (Deut 28:61; 29:20; 30:10; 31:26; Josh 1:8; 8:31, 34; 2 Kgs 22:8, 11) is a retelling—but with some significant revisions and updating—of the earlier “Book of the Covenant” (Exod 24:7; Exod 20–23).

Thus, while it might appear this repeated injunction emphatically excludes any alterations, the book of which these verses are a part presupposes that revisions and updates are a necessary part of the process of applying sacred tradition. The canon is authoritative and the basis for sacred tradition, but the very nature of the traditioning process is that it be interpreted and updated for successive generations. A closed canon should not entail closed thinking.

Info Box 3.1: Whose words are found in the book of Deuteronomy?

A close reading of Deuteronomy’s opening lines reveals the nature of its origins and authority.

These are the words that Moses spoke to all Israel beyond the Jordan … Moses spoke to the Israelites according to all that Yahweh had commanded him concerning them…. Beyond the Jordan in the land of Moab, Moses undertook to elucidate this instruction (torah), saying … (Deut 1:1a, 3b, 5).

The opening incipit identifies this book as the words of Moses. Yet prior to them there was a body of instructional material that Yahweh had earlier commanded Moses to pass on to the Israelites. The book of Deuteronomy itself is defined as Moses’ elucidation of Yahweh’s instruction. In other words, strictly speaking, the book of Deuteronomy is not equated with Yahweh’s words, but with Moses’. Strange as this might seem, this reading appears to accord with Jesus’ interpretation, where he juxtaposes what Moses “allowed” and what God ordained “from the beginning” (Mark 10:2–9 // Matt 19:3–8).

The very injunction in Deuteronomy 12:32 closes a chapter that radically redefines the passage introducing the “Book of the Covenant,” embedded in Exodus 20:22–23:33. Exodus 20:22–26 explicitly allows for multiple altars for sacrifice and worship “in each place where I cause my name to be remembered,” but Deuteronomy 12 explicitly limits Israelite worship to a single altar. When entering the land inhabited by the Canaanites, “you shall tear down their altars” (Deut 12:3).

Centralization increases communication and control.

Instead, the Israelites are to offer all their sacrifices “upon the altar of Yahweh your God” (Deut 12:27). Further, “you shall surely destroy all the places” where the Canaanites worship (Deut 12:2). Indeed, “watch yourselves lest you offer burnt offerings at any place you see” (Deut 12:13). Instead, the Israelites must worship at “the place that Yahweh your God chooses” (Deut 12:5, 11, 14, 18, 21, 26).

Another telling example of how sacred tradition is edited and updated lies in Deuteronomy’s retelling of the Ten Words (Exod 20:2–17). Although the book of Exodus claims the Ten Words were “written with the finger of God” on “the two tablets” (Exod 31:18), the Deuteronomic version changes God’s words in subtle but significant ways. In the tenth Word, the status of women changes considerably:

“You shall not covet your neighbor’s house. You shall not covet your neighbor’s wife, his male servant, his female servant, his ox, his donkey, or anything belonging to your neighbor” (Exod 20:17).

“You shall not covet your neighbor’s wife. You shall not yearn for your neighbor’s house, his field, and his male servant, his female servant, his ox, his donkey, or anything belonging to your neighbor” (Deut 5:21).

The wife is no longer listed among the man’s property. She is first, and she is separated from his possessions. The elevated status of women is corroborated by the retelling of the Hebrew slaves laws in the Book of the Covenant (Exod 21:2–11) as reinterpreted in the Book of the Law (Deut 15:12–18). In Deuteronomy female slaves are newly granted the same civil rights as male slaves. The issue of transgenerational punishment, embedded in the second Word (Exod 20:5–6), is radically reinterpreted in the book of Deuteronomy (Deut 7:9–10; 24:16; cf. Ezek 18; Jer 31:29–30). To our surprise, the very book that prohibits “adding to” and “taking from” the words of Moses reinterprets the very words of Yahweh.

► Isolated verses must be read in the context of their genre. The prohibitions to edit Deuteronomy forbid the vassal from changing a nonnegotiable treaty imposed by the overlord, Yahweh.

How can we resolve this seeming contradiction? Ironically, we can gain some insight from non-Israelite, ancient Near Eastern texts.

In the 1950s archaeologists discovered the Vassal Treaties of Esarhaddon in ancient Nimrud (Calah in the Bible). Scholars have since noted that the book of Deuteronomy mimics this ancient Near Eastern treaty form, in order to illustrate the Israelites’ distinctive understanding of their relationship to Yahweh. In the seventh century BCE the Neo-Assyrian Empire imposed these treaties on their vassal subjects, including Israel and Judah.

In response, the biblical writers imitated this literary genre to make the point that their covenant/treaty was ultimately with Yahweh as their overlord, not a foreign power. An exemplar of this treaty invokes formidable curses “if you change or let anyone change the decree of Esarhaddon, king of Assyria” (§4, ANET, p. 535) and upon anyone “who changes, neglects, transgresses, erases the words of this tablet (§35, ANET, p. 538). A Hittite treaty imposes similar threats upon “whoever … should alter a single word of this tablet” (Hittite Treaty of Tudḫaliya IV with Kurunta of Tarḫuntašša, §24, COS 2.18).

These expressions and those found in the book of Deuteronomy serve as generic formula that are embedded in treaties/covenant documents to underscore that these are nonnegotiable contracts. The point of these formulas is to prohibit the vassal subject from altering the contractual conditions. They are non-negotiable. But should an overlord establish a later treaty/covenant, either he or an appointed official can modify the contract’s prescriptions and conditions at his discretion—especially should circumstances change.

Thus Yahweh, or one of his agents/biblical writers, can modify the earlier Book of the Covenant (= Exodus 20–23) in the later Book of the Law (= Deuteronomy) to suit developing cultural and societal changes. Thus, if 21st century readers of the Bible fail to recognize the literary genre of which these expressions are a part, they are likely to misinterpret them. They are not claims of an unalterable text and closed canon; they simply remind the vassal of their place in the relationship.

The Bible is not a handbook that God dropped from heaven. Rather, it reflects a journey, or pilgrimage as it were, in which God guided his people to discover his way and will. Embedded in biblical revelation is a two-way process: one in which God unfolds revelation and another in which humans simultaneously discover that revelation and refine its articulation over centuries of mutual interaction. Theologians have referred to this as “progressive revelation.”

► Summary observations on the components of the Bible

Below are further general observations on the makeup of the Bible and on how later portions regarded and used earlier sections. They can help us construct an empirical model for understanding the Bible. In short, the Bible is a sacred library of contextual case studies set along trajectories of reinterpretation of traditions. God’s mode of inspiration is “incarnational.”

1. The Bible is sacred, inspired, authoritative.

2. The Bible was not originally a book or an anthology, but a library of sacred scrolls. As a library, this collection contains the enormous variety, spanning thousands of years and multiple social groups and perspectives.

3. The Bible is literature, consisting of a variety of genres, particularly narrative, poetry, legal material, and letters. Systematic theology, consisting of theological propositions, is not one of these.

4. The Bible embodies communication:

Speaker/Author → speech/text → audience ← context/occasion.

As the Bible is regarded to be inspired, God may be considered to be the supreme communicator within this process.

5. Most of the communications in the Bible are contextual (contingent). Their context is thus not merely literary, but includes cultural, social, and historical contexts. Much of the Bible is “occasional literature” (episodic), not a continuous chain of tradition. To this extent, we are reading “someone else’s mail.” The Bible is written for us, but not to us.

6. Language and culture. Hebrew is part of the Semitic family of languages and of the West Semitic family in particular, including Canaanite. As language is a subset of culture, this would include symbols, storylines, and traditions.

7. Tradition, reinterpretation, and revelation. Much of the Hebrew Bible, especially its earliest literature, reinterprets Semitic traditions. And later portions of the Bible reinterpret earlier biblical traditions (see above). In the NT, the OT is often applied typologically to Jesus and the church. In this light, revelation lies in the reinterpretation of the tradition, and not necessarily in the tradition itself.

8. As these communications occur within particular contexts/occasions, we are presented with individual case studies of how God interacts with his people amidst changing social, historical, and personal dynamics. As a library of case studies, the Bible presents us with many canonical conversations that reflect a variety of perspectives.

9. In light of “progressive revelation,” some of these canonical conversations can be mapped along developing trajectories. At certain pivotal moments in Israel’s history and social life, there are emerge paradigm shifts, wherein the identity of God or the people of God may shift dramatically.

10. Within the processes noted above, the Bible consists of human testimony and “incarnational” inspiration, whereby God works principally within the human authors and community, and not from without. In this model Israel’s theology is simultaneously revealed by God and discovered by humans. From the snapshots of human perspectives we can begin to view God’s panoramic perspective.

11. The Bible is simply one element of God’s communication with his people. As the Bible consists of literature, we may discern God’s will by interpreting it within the church community (including past traditions and present interpreters), illumined by the Holy Spirit and discerned by reason, which is informed by interpretation of the natural and social world (God’s creation) and by experience (Deut 30:14; John 7:17).

“The Medium is the Message”: The Genres of Revelation

Marshall McLuhan

► As literature, the contents of the OT are packaged in literary forms or genres, most notably narrative and poetry (not theological discourse).

The Old Testament is not theological discourse. It consists primarily of narrative and poetry. Instead of abstract concepts and ideas, we read of tangible people and events. Instead of universal principles, we are presented with specific examples.

God is not described as an object study, rather he is a subject in stories and songs. God is not defined; he is characterized. Theology speaks in terms of nouns and adjectives; narrative speaks in verbs.

So, for example, in a key passage where Yahweh reveals his personal name and his plans for the exodus (Exod 6:1-8) we read, “the Lord said …, ‘I will do ….’ God spoke further … and said …, ‘I appeared … but … I did not make myself known …. I also established …. I have heard … and I have remembered …. I will bring you out …, and I will deliver you …. I will also redeem …. I will take … I … brought you out … I will bring …, I swore …, and I will give ….”

These differences are not minor, having only to do with the means of revelation. Concepts and adjectives tend to be static and predictable; stories and verbs are dynamic and surprising. These differences also entail strikingly different responses. In our theological systems God, humans, and the world are defined, and so we explain life accordingly and expect life—and God himself—to conform to these propositions and doctrines.

Stories and poems, however, (as their plurality implies) present us with a variety of possibilities for divine behavior. God is not constrained to conform to a certain definition; he is free to follow any number of previous patterns and even to choose a new one. God may act in any number of ways, but he must not act in any single way. Narrative theology allows for the freedom of God.

The Old Testament does not open us to a shopping mall of theologies we may choose according to our own convenience, but stories and poems do present us with a variety of lenses through which we can interpret our experience and God himself. For example:

Are my escalating tragedies to be explained along the lines of Judah’s judgment in exile or of Job’s innocent suffering or of the psalmist’s lament of “why”?

Do I find myself in this oppressive relationship simply because of social reasons (as the Hebrews’ enslavement to Egypt is described in Exodus 1) or because I have rebelled against God?

Instead of detached, dispassionate objectivity, we are to become enmeshed in the drama. As we identify with the characters of the story, we become participants and not mere onlookers. And so in our present life with God, we do not merely theorize (an occupational hazard of academics); we consider our next step.

Another consequence of God’s revealing himself through stories, rather than through universal principles, is that theological truth is always “embedded.” We are not meant to separate the kernel, the timeless truth, from the husk, the historically conditioned people and events.

The whole point to the medium of narrative is that God illustrates how he may speak and perform within particular cultures and with particular people and events. While the theological approach of abstracting timeless truth from Scripture has certainly been endorsed throughout church history (which largely began within a Greek/Hellenistic culture, not a Hebrew/Semitic mindset), these observations show its relative value and subordinate place to Scripture. In our quest for understanding God we must always return to the literature of the Bible itself to hear “the word of God.”

Instead of simply presenting the ideals of what we should believe, the Bible presents ideals and realities, which may or may not be endorsed by their Narrator. This provides greater allowance for complexity, cross-purposes, and ambiguity. In other words, narrative theology makes interpretation more difficult, but also more in keeping with the real world in which we the readers are the players.

Instead of a homogenized point of view, we have canonized points of view. Instead of the message being transcultural, it is now culturally contingent, and these ancient, Semitic cultures are certainly foreign to Western readers.

► Poetry favors figurative language and appeals to the imagination and emotions, even at the expense of precision.

Theological discourse is also markedly different from poetry, which complements narrative by introducing a whole new set of possibilities. Theology uses literal language and concepts; poetry uses figurative language and imagery. Theology engages our logic; and poetry engages our imagination. Theology strives for unambiguous precision, while poetry strives for beauty, even at the expense of ambiguity. Theology emphasizes the cerebral, poetry the emotive. One may be encapsulated in a creed, the other in song. One promotes orthodoxy, and the other worship.

Both have their part to play in the life and growth church, but if spirituality is to thrive, theology must not stifle poetry. Life is both cognitive and affective.

This entails a whole new way of thinking for most Christians. We should relate our experience not merely to our theology or theological system but to the Bible and its manifold revelation.

Sacred Scripture, Sacred Reading

► As sacred scripture, it is appropriate for sympathetic readers to engage in "sacred reading."

“Sacred reading” is vital—literally—in order to ensure that our Bible study is life-giving. In the intricacies and wonder of studying the Bible it’s all too easy that we forget to read it and especially to hear it, as the Bible itself enjoins us in the words of the Shema, “Hear, O Israel …” (Deut 6:4).

In principle, all of our reading and studying Scripture should be part of sacred reading, but in practice it may be best that we consider sacred reading an essential step alongside the tools and skills of Bible study and exegesis.

In the process of studying the Bible we consider words, grammar, literary genre, historical background, biblical cross-references, theology, and so on. But in sacred reading we are deliberate as we step on holy ground and, so to speak, take off our sandals (Exod 3:5; Josh 5:15) and listen to God’s voice. We step beyond the realm of books into the realm of sacred space.

While much of Bible study focuses on what the passage meant in its original context, sacred reading focuses more on what it means to the people of God today, especially its application to contemporary situations. (Admittedly, this is an overly simplistic distinction.) In sacred reading, we listen to God’s present voice through voices from the past. “Sacred reading,” or lectio divina, as it has been called in church tradition, has a clear biblical basis, as this article intends to demonstrate.

Info Box: 3.2: A Personal Confession

Years ago, just before I went to Bible college a friend warned me, “Don’t let the Bible become just another textbook.” At the time I thought his comment was needless and silly. It didn’t take long, however, for the Bible to become simply a resource for a term paper, a dorm Bible study, or a sermon. And now after years of teaching, a new insight from reading the Bible can become simply a profound point to be noted for a lecture, rather than a new insight about the way of God in my life and world. I have discovered that an occupational hazard of being a Bible teacher is that “understanding” the Scriptures can all too easily be exploited and reduced to an intriguing idea to enthuse students in the classroom. The same could be said for personal and group Bible studies.

Craig Broyles, PhD

► As God's teaching was first transmitted during worship services (song came before scripture), so "sacred reading" is meant to revive Bible reading as an act of worship before God.

The Emergence of Scripture in the Development of Israel’s Faith. Before we ask why and how we should read and interpret the Scriptures, we must first look at the role that scriptures played in the development of Israel’s faith.

When and why did Scripture come about?

What events precipitated this act of committing sacred traditions to writing?

Strange as it might sound, the notion of written Scriptures or a Bible would have been anachronistic through most of the Old Testament period. The public reading of God’s “torah” or “instruction” was more the exception than the rule, according to the Old Testament itself. In Exodus 24:3-7 Moses read the “words” (Exod 20:1) and the “judgments” (Exod 21:1) of “the book of the covenant” (Exod 20-23) to the generation of the exodus and Mount Sinai.

The book of Deuteronomy presents itself as a series of Moses’ sermons to the second generation. But the next public reading of God’s written “instruction” recorded in the Bible does not occur until some 600 years later, when “the book of the law” (probably an early edition of the book of Deuteronomy) is discovered during Josiah’s reform (2 Kings 22-23).

(Note: The video below has music; mute your device if desired.)

The next public reading takes place over 160 years later after the exile when Ezra reads “the book of the law of Moses” (probably some form of the Pentateuch) in Nehemiah 8. And in both readings, the people respond as though these sacred texts were new news to their ears.

So how did the people of God learn of their faith during the pre-exilic period or more precisely the First Temple Period?

The principal means were through the hymns, prayers, and prophetic psalms sung at the Temple during the three major pilgrimage festivals (Passover, Weeks/Pentecost, and Tabernacles).

Many of the major blocks of biblical material do not emerge until after the crisis of the exile, when the Babylonians destroyed the Temple, deposed the king, and deported much of the population of Judah in 587 BC. With no available sanctuary for the gathering of God’s people to hear God’s word, the psalms and prophecies that had been sung and proclaimed were “rescued” on the scrolls taken into exile. In addition, they were joined with other sacred scrolls, such as those of “the book of the covenant” and “the book of the law.”

It is in the exilic and early postexilic periods that many of the Old Testament scrolls were compiled and edited into their more or less final editions, such as the Pentateuch, the Deuteronomistic History (i.e., Deuteronomy through 2 Kings, books that share the language, themes, and theological perspective of Deuteronomy), and many of the Prophetic scrolls. This is not to suggest that these scrolls were composed at this late date, only that their regular publication for the awareness of the general public does not occur until the Second Temple Period.

So, in the First Temple period, God’s house was the primary stage, where God and his will were proclaimed in the context of worship, namely through hymns and prophetic psalms, and where the people responded in praise and prayer. Then, in the Second Temple Period there was promoted a second means for the disclosure of God’s will: Torah (i.e., God’s “instruction”).

The gradual shift from Temple to Torah can be illustrated in the Chronicler’s rewriting of First Temple traditions in 1-2 Kings. The pre-exilic phrases, “before me” (1 Kgs 8:25) and “the sight of the Lord” (1 Kgs 14:22), which principally refer to God’s presence at the Temple, are replaced with expressions referring to the God’s “law” or “torah” (2 Chr 6:16; 12:1).

The Torah psalms (Pss 1; 19:7-14; 119) celebrate this new Torah piety. And as made clear by the Roman destruction of the Second Temple in 70 A.D., this shift in Israel’s religion from Temple to Torah was indeed providential.

So we can see that in the absence of the Temple, the written Scriptures come to take center stage. This historical review makes a clear theological point: the proclamation of the sacred traditions that relate God’s self-disclosure to his people originally took place in the context of worship, that is, the living, dialogical encounter between the God of the people and the people of God. And it is this encounter with the living God that the practice of “sacred reading” is meant to restore and promote. As worship includes our experience of God and our affective responses, such as joy and grief, and wonder and fear, so our Bible reading should not be merely a cerebral, scribal exercise.

How to Do “Sacred Reading.”

► Steps of lectio divina

1. Reading (lectio): Reading the text. Listen to the scripture as you read it aloud several times over. What does the biblical text say?

The Hebrew word for “meditating” (הָגָה, hagah) on the Lord’s “instruction” (as in Josh 1:8; Psalm 1:2) actually includes this and the following steps of sacred reading, as the verb literally means “to mutter.” We must keep in mind that silent reading is a relatively recent invention. So biblical meditation is not merely a mental exercise — it is, literally, a dramatic reading.

Our first act of interpretation should always be an attempt to read the passage aloud in a manner that is most appropriate to its literary form (e.g., narrative dialogue, command, lament) and contents. At the same time, we must “hear” what we ourselves are reading, as hearing is fundamental to one’s reception of the Scriptures. We who live in an literate culture have forgotten the skill of listening to the voice of scripture.

Try emphasizing different parts of speech: the verbs or actions in one reading, the subject or actors in another, and the objects receiving the action in yet another.

What is the mood or tone of the passage: joyful or mournful, stern or sarcastic?

Try hearing the passage from different perspectives: as an insider and then as an outsider, as in ancient Israelite, and as a Christian/Gentile.

2. Meditation (meditatio): Thinking about the text. What did and what does the biblical text mean?

Enter imaginatively into the living, breathing world of the text and have a look around. Deliberately step beyond the words on the page into the scene painted by those words.

How are God, the people of God, and outsiders characterized/portrayed?

How does the passage read differently through its expanding circles of context: within its biblical book, the Old Testament, the New Testament, other passages of the same literary genre, other passages of the same historical period, etc.?

What parallels of situation and character types does this passage have with our contemporary world? What differences? How does the passage match our modern-day expectations? What surprises does it offer?

What existential/experiential issues/questions are raised?

Do I genuinely believe what I have read? How do I feel about this passage?

Using the checks and balances of interpretation, how do my subjective impressions square with the plain meaning of the literary text and with my faith tradition?

3. Prayer (oratio): Praying to God about the text. What can I say to God in response to this text?

Narrate to God your own discoveries about the passage, elucidated by questions such as those listed above.

Ask God questions about the passage, and petition God for understanding and for a heart willing to listen.

Ask God for insight as to how this passage should apply to believers today and to situations in our contemporary world.

Offer your own confession, prayer, intercession, thanksgiving, or praise in response to the passage.

If we genuinely believe that the Scriptures are, in fact, “inspired by God,” then one of our first acts of interpretation, if we are puzzled by a passage, should be to ask God about it. In most cases, the answer will not be instant but will involve a process of “asking, seeking, and knocking” (Matt 7:7-8) and “examining the Scriptures daily” (Acts 17:11).

4. Contemplation (contemplatio): Listening to God. What is God saying to his people through this scripture?

In this stage we listen to God in the quietness of the heart, and we are intentionally open to God’s answering our questions by the illumination of the Holy Spirit. By definition, this stage of sacred reading cannot be taught, because here we defer to God and his discretion, thereby acknowledging his freedom to speak and to act as he chooses. And as made clear in Jeremiah’s “new covenant” oracle, ultimate understanding is attained when the Scriptures are, in fact, internalized by God’s own action: “I will put my law within them, and I will write it on their hearts … No longer shall they teach one another, or say to each other, “Know the Lord,” for they shall all know me …” (Jer 31:33–34). In this respect, we allow God’s word to change us from within.

One of the key differences in sacred reading is that we hear holy Scripture in the context of relationship with God as a personal (though not always private or intimate), living communication. We are not merely reading and studying an ancient document, literary art, or a historical and religious artifact. It is not merely text; it is speech. If, indeed, we genuinely believe that “scripture” can be characterized as “inspired by God” (2 Tim 3:16), then we must hear divine speech through these Scriptures. Sacred reading is not quantitatively different from studying the Bible, whether by believer or secularist, in the sense that it yields new information, data, or secrets about the literary text. Rather, it is qualitatively different, in the sense that it becomes personal and is understood subjectively. The difference lies in understanding that not only did ancient Israel believe that God loved them, but that God actually loves his people now, which includes me. Sacred reading brings the “Aha!” back into Bible study.

5. Action (actio): Acting in thought and deed. How will I change my thinking and my behavior today in response to hearing this text?

The encounter engendered by sacred reading is meant to affect concretely our daily life and work in the world. At the end of his last “sermon” in the book of Deuteronomy, Moses presents a fine summary of the practice of “sacred reading,” or perhaps more accurately, “sacred confession and action”:

“Surely, this commandment that I am commanding you today is not too hard for you, nor is it too far away. It is not in heaven, that you should say, “Who will go up to heaven for us, and get it for us so that we may hear it and observe it?” Neither is it beyond the sea, that you should say, “Who will cross to the other side of the sea for us, and get it for us so that we may hear it and observe it?” No, the word is very near to you; it is in your mouth and in your heart for you to observe.” (Deut 30:11–14, NRSV)

The Bible is not about divine secrets and mysteries merely for the super-spiritual, nor is it bound to a particular sacred space to which we must make pilgrimage. It is now accessible to all who willing to confess it, embrace it, and do it. The word of God is more than a good book in our hands (the habit of the literate culture), but it is meant to be expressed as a word in our mouth (the forgotten habit of an ancient, oral culture), to be incorporated in our heartfelt motives, and to be incarnated in our actions. It is in doing the will of God that we discover that the Bible’s teaching, in fact, originates from God (see John 7:17). Long before modern psychology, the ancient Scriptures exhibited profound insight into holistic approaches to human existence. Sacred reading touches all aspects of the human personality: its cognitive, affective, and behavioral components, that is, our knowing, feeling, and doing. God’s word acts and does things to its listeners/readers. It is not merely “objective revelation” that promotes cerebral exercise. It is “like fire” (Jer 23:29). It is to be “at work in you believers” (1 Thes 2:13). It is “living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword, piercing until it divides soul from spirit, joints from marrow; it is able to judge the thoughts and intentions of the heart (Heb 4:12).