8th Century Prophecy

► Classical prophecy emerges on the eve of the Assyrian empire and Israel's loss of independence.

The prophetic books of the OT begin somewhat late in the history of Israel and Judah. The tribes settled in the land around 1200 BCE and David’s reign begins around 1000 BCE, but the prophets, whose oracles are collected in the prophetic books, do not enter the stage until the middle of the 8th century BCE. So why at this moment? It can be helpful to step back from the literature of the OT to consider the wider stage of the ancient world. Simultaneous with the emergence of the OT prophets was the rise of Tiglath-pileser III to the throne, who transformed Assyria from a kingdom to an empire. Israel and Judah were about to lose their political independence and become vassal states absorbed within a foreign empire. The default mode of thinking within the wider Semitic culture would lead to the conclusion that the army victorious on the battlefield had the superior patron deity. The patron deity of the subjugated state would simply be absorbed within the pantheon of the victorious deity. In other words, without the predictive and explanatory word of the OT prophets, Yahwism might have ended right there.

► When the 8th- century prophets preached, little of the Bible had been "published" to the people.

The table of contents of the Bible places the Pentateuch (Torah in the Hebrew Bible) and the historical books (the Former Prophets in the Hebrew Bible) before the (Latter) Prophets. But if we are to enter the world of the eighth-century prophets, we must recognize that little of the Bible had yet been “published” to the people of Israel and Judah. The first explicit mention of the public reading of a biblical book during the monarchy comes during the reign of Josiah in 622 BCE (2 Kgs 22–23)—a full century after the eighth-century prophets. So we cannot assume that they and especially their audiences knew the full story of the Hebrews, along with their covenant with Yahweh at Mount Sinai. What they knew and what they did not know we will have to reconstruct when we examine the traditions embedded in these prophetic books.

Amos

1. Canonical and Historical Context: Who’s on stage?

Amos preaches during the reign of Jeroboam II (786–746 BCE) while the northern kingdom of Israel still enjoyed political independence. Shortly after the Israelite king’s death Tiglath-pileser III came to the throne of Assyria, and he would transform his kingdom into an empire, eventually incorporating Israel as a vassal. The lack of any explicit reference to an Assyrian threat confirms the dating within Jeroboam’s lifetime.

Shortly after the ministry of Amos, Hosea delivers his message to northern Israel. Later in the 8th century, Isaiah and Micah preach to the southern kingdom of Judah.

2. Outline and Key Passages

(coming later)

3. Situation and Message: What’s at Stake?

► What is the purpose of religion? Why did God choose a people?

While studying the Old Testament, it is easy to get lost in the texts themselves without giving due attention to the wider issues reflected in these texts. The book of Amos profoundly addresses the fundamental question, what is the purpose of religion? For whose benefit is it: the deity’s, the worshiper’s, or the wider society’s? Is it a private or public matter? It also addresses the fundamental theological question of “election,” that is, does God have a “chosen people,” and if so, is this a privilege or responsibility, or both?

► Yahweh called Amos to preach a message of judgment on Israel's official religion when it appeared the nation was prospering under God's blessing.

Amos at Bethel (Amos 7:10–17). Amos’s ministry was centered at Bethel, a royal sanctuary just north of Israel’s border with Judah—during the reign of Jeroboam II (Amos 1:1). Observing his social location helps to make sense of the striking contrast in the nearly contemporary ministries of Amos and Hosea, who preached to the same generation in northern Israel. Hosea’s ministry focused on popular religion (i.e., the religion of the common people), where both Yahweh and Baal were worshiped. He identified Israel’s principal sins as infidelity and idolatry. These sins barely surface in the book of Amos. His indictments focused on the official religion of the state of Israel, whose patron was Yahweh. As a result, he was confronted by Amaziah, “the priest of Bethel.” He invoked royal and priestly privilege over against any prophetic criticism: “but at Bethel you shall not again prophesy, for it is the king’s sanctuary, and it is a house/temple of the kingdom” (Amos 7:13). According to 1 Kings, Jeroboam I, the first king of the northern kingdom of Israel, had instituted sanctuaries in Bethel and Dan, as alternatives to the Jerusalem temple, and he appointed non-Levitical priests at Bethel (1 Kgs 12:26–33).

The odds were stacked against Amos. Jeroboam II enjoyed a long forty-year reign during a time of agricultural and economic prosperity, which his subjects would have interpreted as a sign of Yahweh’s blessing on his kingdom. The “haves” in Israel had considerable wealth: winter and summer houses (Amos 3:15–4:1), and parties with rich feasting and imbibing (Amos 6:4–6). In fact, he expanded Israel’s borders—apparently with God’s blessing.

“He restored the border of Israel from Lebo-hamath as far as the Sea of the Arabah, according to the word of the Lord, the God of Israel, which he spoke by his servant Jonah son of Amittai, the prophet, who was from Gath-hepher” (2 Kgs 14:25, NRSV).

No one, especially those in power, wanted to hear doom and gloom when the kingdom was clearly prospering. Yet Amos appears to mimic Jonah’s earlier prophecy, but this time to notify Israel of its reversal:

Indeed, I am raising up against you a nation,

O house of Israel, says the Lord, the God of hosts,

and they shall oppress you from Lebo-hamath

to the Wadi Arabah (Amos 6:14, NRSV).

Amos suffered another disadvantage: he was a foreigner from the rival state of Judah. He also lacked prophetic credentials: “I am no prophet, nor a prophet’s son; but I am a herdsman, and a dresser of sycamore trees, and the Lord took me from following the flock, and the Lord said to me, ‘Go, prophesy to my people Israel’” (Amos 7:14–15, NRSV). He describes himself as “a herdsman and a picker of sycamore figs” (Amos 7:14). The superscript of the book describes him similarly as one of the “sheep-breeders [nqd] from Tekoa,” just south of Bethlehem in Judah. This term does not necessarily place Amos among the so-called working-class, as this role is also attributed to Mesha king of Moab (2 Kings 3:4) and to high officials in ancient Ugarit. The perils of his situation could be compared to a corporate farmer from Pennsylvania being called to preach in Atlanta just prior to the Civil War in the United States! Not surprisingly, Amaziah orders him to go home and mocks him as a “seer” who “drivels” or “foams at the mouth” like an ecstatic (Amos 7:16, literal).

Finally, Amaziah misquotes Amos and accuses him of conspiracy against the king. He quotes him as saying,

“For thus Amos has said,

‘Jeroboam shall die by the sword,

and Israel must go into exile

away from his land.’ ” (Amos 7:11, NRSV)

This claim seems problematic because 2 Kings 14:29 indicates that Jeroboam died of natural causes. We can search the book of Amos for confirmation of this claim, but the closest oracles are these below. The first comes from the passage immediately preceding.

The high places of Isaac shall be made desolate,

and the sanctuaries of Israel shall be laid waste,

and I will rise against the house of Jeroboam with the sword.” (Amos 7:9, NRSV)

But do not seek Bethel,

and do not enter into Gilgal

or cross over to Beer-sheba;

for Gilgal shall surely go into exile,

and Bethel shall come to nothing. (Amos 5:5, NRSV)

According to Amos’s own words, the sword threatens “the house of Jeroboam,” that is, his dynasty and kingdom—not the king personally.

► Yahweh judges Israel's neighboring states for general acts of inhumanity, but judges Judah and then Israel for violations against Yahweh's teaching.

Oracles against the Nations (Amos 1:3–2:16). Given his uphill battle, the final redaction of the book of Amos suggests that the prophet employed a shrewd rhetorical device to gain traction with his Israelite audience. He begins his indictments with the nations and cities bordering Israel, each of whom was a rival and threat: Damascus, Philistine cities (Gaza, Ashdod, Ashkelon, Ekron), Tyre, Edom, Ammon, Moab, and most importantly Amos’s own Judah. One can imagine the rising crescendo of “Amens” among his northern audience as he announces Yahweh’s judgment on these opponents, especially during the climactic oracle against their chief rival of Judah. Each oracle repeats the same phrases:

Thus has Yahweh said:

For three transgressions of …, and for four I will not revoke it [i.e., a verdict of punishment],

because they ….

So I will send fire on …

These oracles give us insight into the relative standards that Yahweh applies to outsider groups and to the insider groups of Judah and Israel. To what extent is each accountable to God? Judah’s “transgressions” are defined as their rejection of “Yahweh’s law” and “statutes,” which Yahweh had specially disclosed to them (Amos 2:4). The other nations, however, are indicted for general acts of inhumanity: military cruelty (e.g., “they ripped open pregnant women,” Amos 1:13), faithlessness to a treaty/covenant relationship—possibly including slave trade (Amos 1:9, 11), and abuses of power. Some of these acts were perpetrated against Israel, though not all: Moab “burned to lime the bones of the king of Edom” (Amos 2:1).

But once Amos says, “for three transgressions of Israel,” one can imagine the shock and hush of his Israelite audience. Their “Amens” to the previous judgment oracles have set the stage for their own condemnation.

►► STUDENTS MAY SKIM FROM HERE TO THE NEXT DOUBLE BULLET ►►.

► Amos's appeals for justice echo, but do not quote, traditions also found in the Sinai Covenant Code (Exod 21-23).

The Traditions of Amos and His Audience. By what standards does Yahweh judge northern Israel? What were his expectations of his people? What traditions does Amos employ, and what traditions are evidently known to his audience? What is the official religion at Bethel and the other named sanctuaries of the north? And how does Amos utilize these traditions to persuade the Israelites that they must change their ways?

To our surprise, while Judah has “Yahweh’s law” and “statutes” (Amos 2:4), the book of Amos contains no appeals to written torah/instruction for northern Israel. Although Amos’s oracles may use phrases and refer to events and locations that are also mentioned in the Pentateuch, there are no clear indications that he is citing or referring to written texts or scriptures. Pentateuchal laws and narratives nowhere form the basis of his indictments. The book of Deuteronomy is clear that there should be only one legitimate sanctuary among God’s people (Deut 12:5, 11, 13–14) and the Deuteronomistic historian regards Jeroboam’s sanctuaries of Bethel and Dan as “a sin” (1 Kgs 12:30). Yet Amos nowhere advocates for the Deuteronomic centralization of worship.

To ascertain how traditions surface in the book of Amos we shall begin with the clearer echoes of shared traditions, first in the “oracle against the nation” addressed to Israel (Amos 2:6–19).

Info Box 17.1: Citation or Echo of the Covenant Code?

Amos’s oracle against Israel uses phrases also found in the Sinai Covenant Code (Exod 20:22–23:33). The phrase “garments seized in pledge” (Amos 2:8) echoes one of its laws:

If indeed you seize your neighbor’s garment in pledge, at sundown you shall return it to him, for it is his only covering, it is his garment for his body; in what else shall he sleep? (Exod 22:26–27)

But we must be careful to observe that this is simply an echo, not a citation. The prophet does not use the Covenant Code to indict the Israelites, as he makes no explicit mention of loans or the return of garments at nightfall. He simply uses this image to illustrate a more scandalous sin of using these garments as bedding for illicit sexual activity right beside the altar. Hence, it is not even clear whether Amos is referring to a written text such as the Covenant Code or simply to laws that were customarily known in wider society.

What is surprising is that Amos makes no reference to the preceding law in the Covenant Code, which explicitly prohibits oppression and mistreatment of sojourners, widows, and orphans (Exod 22:21–24). Indeed, in this oracle (Amos 2:6–7) and throughout the book, Amos advocates for the needy, the poor, and the afflicted above all else. One would imagine that an explicit appeal to covenant legislation could add considerable authority to his oracle, but he does not do so.

Other phrases in this oracle may echo another law in the Covenant Code:

“Selling the righteous … and the needy” and “turning aside the way of the humble” (Amos 2:6–7)

“You shall not turn aside the justice of your needy in his lawsuit…. The innocent and the righteous you shall not kill” (Exod 23:6–7).

But again this is not a citation; otherwise we should expect Amos to say, “turning aside the justice of the needy.”

In a later oracle Amos uses similar phrasing that echoes this same passage in the Covenant Code:

“you who distress the righteous, who take a bribe [kōp̄er], and who turn aside the needy in the gate” (Amos 5:12)

“You shall not turn aside the justice of your needy in his lawsuit…. The innocent and the righteous you shall not kill …. And a bribe [šōḥad] you shall not take ” (Exod 23:6–8).

This is not a quotation: each passage uses a different Hebrew word for “bribe” and a different prepositional phrase, “in the gate” versus “in his lawsuit.”

►

Exodus, Wilderness, and Conquest. The most prominent tradition in the book of Amos is that of the exodus from Egypt, along with some references to the wilderness and the conquest. Amos juxtaposes Israel’s religious and social abuses (Amos 2:6–8) with Yahweh’s escort out from Egypt and through the wilderness and especially with his destruction of the Amorite (Amos 2:9–10). Emphasis is given to Yahweh’s power to “destroy” the Amorites who were “rooted” in the land. Yahweh’s impending judgment on Israel (“Behold, I am about to …”) will be to disable Israel’s champion warriors (Amos 2:13–16). Amos does not go in the direction we might expect. He highlights Yahweh’s power to destroy and disable mighty warriors, not his social liberation from slavery and injustice in the exodus, which would demonstrate the Israelites’ presumptuous role reversal of “selling” their own people.

Info Box 17.2: “The land of the Amorite”

Another curiosity is Amos’s source of this conquest tradition. Yahweh had led his people “to possess the land of the Amorite” (Amos 2:10). Throughout the book of Exodus the Amorites are always listed among the six “–ites” residing in the promised land, where Canaanites are usually listed first (Exod 3:8; 23:23; 34:11, etc.). The same applies in the book of Deuteronomy (Deut 7:1; 20:17), unless the term refers just to the Amorites who reside in Transjordan to the east (esp. Sihon the king of the Amorites, Deut 1:4; 3:2, etc.). The only other passages that identify the Amorites as the sole residents of Canaan are Genesis 15:16 (in contrast to Gen 15: 18–20, which immediately follows), Joshua 24:8, 15, 18 (in contrast to the intervening verses in Josh 24:11, 12) and Judges 6:10.

In two other important oracles Amos alludes to the exodus, but he reverses the popular understanding of that tradition.

Hear this word that Yahweh has spoken against you, O people of Israel, against the whole family that I brought up out of the land of Egypt:

Only you have I known

of all the families of the earth;

therefore I will call you to account

for all your iniquities (Amos 3:1–2).

Yahweh indeed affirms his special relationship with the family of Israel (“you only have I known”). While the official and popular religion of northern Israel would assume “election” entails special favors, in Amos’s prophecy it entails special accountability. The phrase “all the families of the earth” may also echo the election tradition of the ancestral promises (Gen 12:2; 28:14).

An even more radical reversal occurs in a later passage:

Are you not like the Ethiopians to me,

O people of Israel? says the Lord.

Did I not bring Israel up from the land of Egypt,

and the Philistines from Caphtor and the Arameans from Kir?

The eyes of the Lord God are upon the sinful kingdom,

and I will destroy it from the face of the earth

—except that I will not utterly destroy the house of Jacob,

says the Lord (Amos 9:7–8, NRSV).

Yahweh affirms that he did “bring up Israel from the land of Egypt,” but he now disclaims that it was anything special among the other migrations that he caused!

Info Box 17.3: Illustrative and Subtle Echoes of Pentateuchal Traditions

Elsewhere the book of Amos contains expressions or place names that echo pentateuchal traditions, but they appear simply to illustrate Yahweh’s actions. They do not form the basis or standard by which Yahweh is judging his people. Amos 4:6–11 lists a series of five past judgments that Yahweh had sent upon Israel that end with the refrain, “but you did not return to me.” Two of these judgments are likened to judgments in the Pentateuch:

I sent among you a pestilence after the manner of Egypt …

I overthrew some of you, as when God overthrew Sodom and Gomorrah … (Amos 4:10–11).

Other echoes are more subtle. Yahweh threatens to bring lamentation among the urban and rural populations, “because I will pass through [‘br] in your midst” (Amos 5:17), just as Yahweh had passed through Egypt on the night of the Passover when he struck their firstborn (Exod 12:12, 23). During two of Amos’s visions, Yahweh threatens, “I will never again pass by [‘br] them” (Amos 7:8; 8:2), in effect denying Israel any future theophanic appearances—the kind that he had revealed to Moses on Mount Sinai (Exod 33:19, 22; 34:6).

Sacrifices in the wilderness? In a prose oracle Yahweh asks his people a rhetorical question, expecting the answer “no”: “Did you bring to me sacrifices and offerings in the wilderness those forty years, O house of Israel?” (Amos 5:25). This understanding appears to be at variance with the priestly traditions of the Pentateuch (i.e., P), especially the book of Leviticus and Leviticus 9:8–24 in particular. On the other hand, the prophet Jeremiah appears to be on the same page as Amos:

For in the day that I brought your ancestors out of the land of Egypt, I did not speak to them or command them concerning burnt offerings and sacrifices. But this command I gave them, “Obey my voice, and I will be your God, and you shall be my people; and walk only in the way that I command you, so that it may be well with you.” (Jer 7:21–23, NRSV)

(The understanding that ritual sacrifice was not commanded or practiced during the wilderness period is consistent with the JE traditions of the Pentateuch, where sacrifices were offered during the original Passover in Egypt [Exod 12:21–27] and at Mount Sinai [Exod 3:12; 17:15; 24:4–8; 32:5–6], but not in the wilderness.)

Sanctuaries of Bethel and Gilgal. What traditions legitimated Bethel as a sanctuary for Yahweh? Bethel’s priest, Amaziah, asserted, “it is a royal sanctuary and a house of the kingdom” (Amos 7:13), which likely refers to the institution of the sanctuary by Jeroboam I a century and a half earlier (1 Kgs 12:26–33). The association of “the house of Jacob” with “the altar(s) of Bethel” (Amos 3:13–14) may echo the theophanies that the patriarch Jacob experienced at Bethel and commemorated by erecting a sacred “standing stone” (Gen 28:10–22; 35:1–15) and an altar (Gen 35:1, 3, 7). If so, the point of Amos’s allusion to this story would be to illustrate Yahweh’s reversal by cutting off the horns of its altar. On the other hand, the expression, “the house of Jacob,” may simply be another expression for the kingdom of Israel, as it is in Amos 9:8. “Israel’s transgressions” in this passage (Amos 3:14) clearly belong to those of the kingdom, not to the patriarch Jacob/Israel.

Bethel and Gilgal are mentioned together elsewhere (Amos 4:4–5; 5:4–6), but they are not connected to their stories and sacred markers in Genesis or in Joshua (Josh 4:19–24; 5:9–10). Instead, the prophet employs Hebrew word plays (e.g., “Gilgal will indeed go into exile [galoh yigleh]”). Other sacred spaces are mentioned in Amos 8:14: “the Asherah of Samaria,” “your God” of “Dan,” and “the way/beloved of Beersheba.

Info Box 17.4: Other Traditions

The singling out of “the new moon” and “the Sabbath” (Amos 8:5) as prominent holidays for ritual observance occurs especially among the eighth-century prophets (Isa 1:13; Hos 2:11; cf. 2 Kgs 4:23; Isa 66:23), but not among the pentateuchal traditions. The new moon as a feast day for the people is also mentioned during the life of David (1 Sam 20:5, 18, 24, 27, 34) and in Psalm 81:3.

Amos also alludes to the Nazirite vow (Amos 2:11–12; Num 6:1–21). And he mentions David’s skills with musical instruments for the sake of illustration (“like,” Amos 6:5; 1 Sam 16:16–18, 23; 18:10; 19:9).

Amos invokes a curse, which is also found among the Deuteronomic curses:

“Houses of human stones you have built, but you shall not dwell in them;

pleasant Vineyards you have planted, but you shall not drink their wine” (Amos 5:11).

“A house you shall build, but you shall not dwell in it.

A vineyard you shall plant, but you shall not make common use of it” (Deut 28:30).

“Vineyards you shall plant and work, but wine you shall not drink …” (Deut 28:39).

It is not clear, however, whether he is pointing specifically to these curses written in “the Book of the Law” or simply invoking common curse formulas.

“The day of Yahweh” (Amos 5:18–20).

Alas for you who desire the day of the Lord!

Why do you want the day of the Lord?

It is darkness, not light;

as if someone fled from a lion,

and was met by a bear;

or went into the house and rested a hand against the wall,

and was bitten by a snake.

Is not the day of the Lord darkness, not light,

and gloom with no brightness in it? (Amos 5:18–20, NRSV)

The tradition underlying the phrase, “the day of Yahweh,” has been debated among scholars. Amos clearly did not coin the expression, as this oracle indicates it was popular expectation of the people. But again he reverses the expectation: it will be “darkness, not light.” The wider context of the chapter places this tradition alongside the worship services at local sanctuaries, such as Bethel and Gilgal (Amos 5:4–6, 14–15, noting the repetition of the command to “seek”), where they held their feasts and performed ritual sacrifice (Amos 5:21–27). The expectation of “light” and “brightness” suggest a theophany/appearance of Yahweh on behalf of his people (“he has dawned … he has shone forth,” Deut 33:2), especially to judge their enemies (Pss 18:12; 80:1; 94:1). Similarly, in the doxology found in the same chapter, Yahweh “darkens the day into night” (Amos 5:8).

God of the Skies. In one of Amos’s best-known passages he strangely likens justice to rolling waters:

“But let justice roll like waters,

and righteousness like a perennial stream” (Amos 5:24).

This exhortation is in direct contrast to his previous indictment against “those who turn justice to bitter wormwood, and righteousness they cast to the earth” (Amos 5:7). Interrupting, so to speak, Amos’s indictments against the people is the second of his three doxologies. (Scholars have debated whether or not these doxologies were later insertions, though more recent scholars affirm their authenticity.) The effect is to contrast the Israelites “who turn [hp̄ḵ] justice to bitter wormwood” with Yahweh “who turns [hp̄ḵ] the shadow of death to morning”:

The one who made the Pleiades and Orion,

and turns deep darkness into the morning,

and darkens the day into night,

who calls for the waters of the sea,

and pours them out on the surface of the earth,

the Lord is his name,

who makes destruction flash out against the strong,

so that destruction comes upon the fortress (Amos 5:8–9, NRSV).

So, Yahweh can bring either destruction or life-giving waters. As the God of the Skies pours out life-giving waters, so his people are to “roll out” justice and righteousness like waters. (Cf. Amos 5:24 also with Ps 104:10.)

Yahweh’s admonition to let righteousness roll “like a perennial stream” (Amos 5:24) echoes Yahweh’s provision of “streams” for creation’s benefit in the biblical psalms, which were the liturgical texts for public worship (Pss 74:15; 104:10).

The other two doxologies in Amos likewise echo the celebration of the God of the skies found in the Psalms (cf. Amos 4:13 and Ps 65:5–8; Amos 9:5–6 and Ps 104:3, 5, 13, 32). Central to each of the three doxologies is the refrain, "Yahweh is his name," thus underscoring that the identity of the God of the skies is Yahweh, and no other. (Cf. also the theophanies of judgment that open their respective books: Amos 1:2 and Micah 1:2–4.) The rationale for these connections is best illustrated in Psalms 50 and 97, where the God of the skies/heavens vanquishes chaotic forces (Pss 50:1–6; 97:1–6), thus “proclaiming his righteousness” (Pss 50:6; 97:6). This drama thus publishes Yahweh's attribute of "putting things right." He establishes right-order in nature and in turn expects it in human society.

To our surprise, Amos’s understanding of “righteousness” and “justice” stems more from the tradition of the God of the skies known from the Psalms, than from Mosaic Torah.

►► RESUME READING HERE ►►.

In view of the above, the kind of religion under which Amos operates does not appear to be one based on authoritative scripture. His arguments are more humanistic than scriptural. His rhetoric, “selling/buying the righteous/poor for silver and the needy for a pair of sandals” (Amos 2:6; 8:6), is compelling in its own right by illustrating how the Israelites reduce their fellow Israelites to commodities. He appeals to the virtues of doing righteousness and justice and what is good (Amos 5: 14–15, 24). For Amos religion is demonstrated in the marketplace, not in temple rituals.

Admonitions and Judgment Oracles on Israel Sins. What are the principal sins of Israel that Amos indicts? Fundamentally they are social oppression and religious hypocrisy, which go hand in hand, as his opening oracle against Israel illustrates.

Thus says the Lord:

For three transgressions of Israel,

and for four, I will not revoke the punishment;

because they sell the righteous for silver,

and the needy for a pair of sandals—

they who trample the head of the poor into the dust of the earth,

and push the afflicted out of the way;

father and son go in to the same girl,

so that my holy name is profaned;

they lay themselves down beside every altar

on garments taken in pledge;

and in the house of their God they drink

wine bought with fines they imposed (Amos 2:6–8, NRSV).

Religion had become a tool for social manipulation. The phrase, “in order to profane my holy name,” while not explicitly referring to the Third Commandment, illustrates what it is to “take the name of Yahweh your God in vain” (Exod 20:7): it is to invoke the name of God for manipulative purposes.

Indeed, one could not accuse Israel of not being religious.

Come to Bethel—and transgress;

to Gilgal—and multiply transgression;

bring your sacrifices every morning,

your tithes every three days;

bring a thank offering of leavened bread,

and proclaim freewill offerings, publish them;

for so you love to do, O people of Israel!

says the Lord God (Amos 4:4–5, NRSV).

Amos appears to parody the traditional call to worship in order to suggest that their religion ironically promotes transgression. The reason seems to lie in their love of “publishing” their offerings. We can gain some insight from Leviticus 1, which lists three possible options for “a burnt offering”: a bull from the herd, a sheep or goat from the flock, or a bird. In other words, the number and kind of sacrifices offered by worshipers could indicate their income tax bracket and their apparent devotion to Yahweh. According to Amos, religion can mask hypocrisy. The Israelites use it to promote their self-importance among their peers.

In the next chapter Yahweh indicates the Israelites’ have missed the point of religious observances.

For thus says the Lord to the house of Israel:

Seek me and live;

but do not seek Bethel,

and do not enter into Gilgal

or cross over to Beer-sheba;

for Gilgal shall surely go into exile,

and Bethel shall come to nothing.

Seek the Lord and live,

or he will break out against the house of Joseph like fire,

and it will devour Bethel, with no one to quench it (Amos 5:4–6, NRSV).

He seeks to refocus their religious attention to Yahweh himself and away from the sanctuaries, where the religious symbols and rituals have overshadowed the deity they pretend to worship. The consequences are either “living” or “going into exile.”

What happens when God does not attend his people's worship service? God seems irritated with their worship songs and music, which appear to have elicited the extremes of Yahweh’s emotions.

I hate, I despise your festivals,

and I take no delight in your solemn assemblies.

Even though you offer me your burnt offerings and grain offerings,

I will not accept them;

and the offerings of well-being of your fatted animals

I will not look upon.

Take away from me the noise of your songs;

I will not listen to the melody of your harps.

But let justice roll down like waters,

and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream (Amos 5:21–24, NRSV).

The Israelites appear to have assumed the religious perspectives common in their wider Semitic culture. Temple observances were primarily for “the care and feeding of the gods” and had little to do with daily life in human society. But Yahweh’s expectations are countercultural and unlike those of other so-called gods in the ancient Near East. He values the fair treatment of the neighbor over the ritual observances of sacrifice and song. The Israelites believed their sacrifices obliged God to favor them. Yahweh asserts their religion obliges them to act fairly to their fellow Israelites. Indeed, sacrifice does not appear to have been part of their previous relationship in the wilderness (Amos 5:25).

But when all is said and done, while the Israelites may love their religion, they love commerce and consumerism still more, even at the expense of the poor.

Hear this, you that trample on the needy,

and bring to ruin the poor of the land,

saying, “When will the new moon be over

so that we may sell grain;

and the sabbath,

so that we may offer wheat for sale?

We will make the ephah small and the shekel great,

and practice deceit with false balances,

buying the poor for silver

and the needy for a pair of sandals,

and selling the sweepings of the wheat” (Amos 8:4–6, NRSV).

Visions (Amos 7:1–9) and the phases of Amos’s ministry. Amos’s first two visions follow the same pattern: Yahweh shows him an impending disaster (a swarm of locusts, Amos 7:1–3, and fire, Amos 7:4–6), he intercedes for mercy, and Yahweh relents. In this respect, we perceive that a prophet’s role was not merely to mediate Yahweh’s message to the people but also to mediate with Yahweh on their behalf. The third vision is different.

This is what he showed me: the Lord was standing beside a wall built with a plumb line, with a plumb line in his hand. 8 And the Lord said to me, “Amos, what do you see?” And I said, “A plumb line.” Then the Lord said,

“See, I am setting a plumb line

in the midst of my people Israel;

I will never again pass them by;

the high places of Isaac shall be made desolate,

and the sanctuaries of Israel shall be laid waste,

and I will rise against the house of Jeroboam with the sword” (Amos 7:7–9, NRSV).

It would seem to Yahweh’s patience has reached its full, and judgment is now inevitable. This development suggests that in the earlier phase of Amos’s ministry he sought to elicit repentance, thus averting impending judgment, such as we see in his admonition, “seek Yahweh and live, lest he break out like fire …” (Amos 5:6).

The Book of Amos for the Kingdom of Judah. Amos’s message was addressed to the northern kingdom of Israel, which the Assyrians wiped from the map in 722 BCE. But his words live on. They survived, eventually to become part of the Scriptures of Judah to the south. Although not addressed to Judah directly, they were evidently considered meaningful and relevant to a Judahite readership. The bookends formed by the opening and closing passages attest to a Judahite edition of the book in its final form (note also Amos 6:1).

And he said:

The Lord roars from Zion,

and utters his voice from Jerusalem;

the pastures of the shepherds wither,

and the top of Carmel dries up (Amos 1:2, NRSV)

On that day I will raise up

the booth of David that is fallen,

and repair its breaches,

and raise up its ruins,

and rebuild it as in the days of old;

in order that they may possess the remnant of Edom

and all the nations who are called by my name,

says the Lord who does this.

I will restore the fortunes of my people Israel,

and they shall rebuild the ruined cities and inhabit them;

they shall plant vineyards and drink their wine,

and they shall make gardens and eat their fruit (Amos 9:11–12, 14, NRSV).

The closing oracle is the only note of hope in the entire book. For the Israelites of the north, however, this hope for restoration would have been a hard pill to swallow. It entails re-unification with their rival Judah under a Davidic monarch. But Judahite readers would view this with patriotic anticipation.

The dating of this oracle has been debated. It is clearly future (“in that day”), but it also presupposes “the falling/fallen booth of David.” Either the Davidic kingdom is in decline, as in Sennacherib’s invasion during the reign of Hezekiah in 701 BCE (2 Kgs 18:13–16), or the Davidic kingdom has fallen entirely, as in the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem in 587 BCE. Either way, it is likely that this final oracle was added later to Amos’s original oracles.

Info Box 17.5: The Citation of Amos 9:11–12 at the Jerusalem Council (Acts 15:15–18)

(coming later)

4. Canonical and Theological Contribution

The bottom line for Amos's ministry at Bethel is to unmask the elites who use religion as a tool to justify themselves and to exploit others. In a word, they act "to profane my holy name" (Amos 2:7).

Many readers avoid the Prophets because they seem so negative, preaching gloom and doom—especially Amos. Yet, with respect, we must ask, why does God get so angry? Simply put, because his values have been violated. Thus, behind each negative judgment oracle, there is reflected a positive virtue of God. If God abhors religious hypocrisy, then it is because he values religious authenticity. If he abhors social injustice and oppression, then he must cherish fairness and liberty for his people.

In the New Testament Paul illustrates this principle when he summarizes the negatively stated Ten Commandments ("you shall not ...") in the word, "You shall love your neighbor as yourself" (Rom 13:8-10). Although Amos's book does not refer to this great commandment, his ministry exemplifies the value of "loving your neighbor as yourself" (Lev 19:18).

Isaiah 1-39

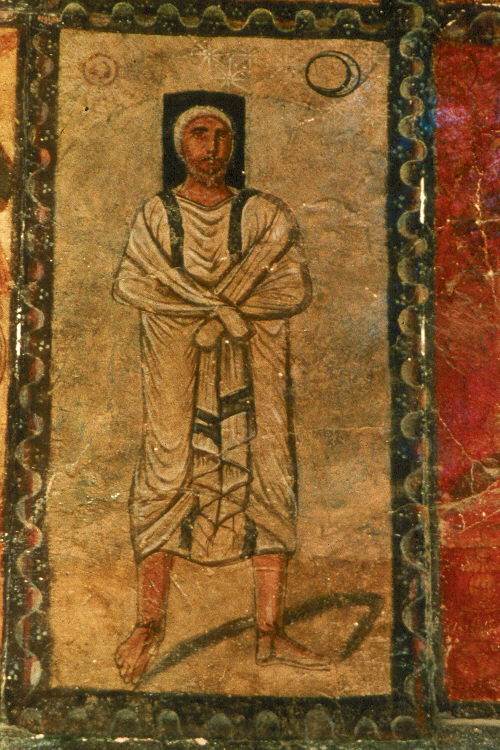

Depiction of Isaiah in a Jewish Synagogue in Roman Mesopotamia (3rd CE)

Canonical and Historical Context: Who’s on Stage?

The Book of Isaiah. No prophetic book has a wider historical scope than the book of Isaiah, which spans the pre-exilic, exilic, and postexilic periods from roughly the mid-eighth century to the end of the sixth century BCE. Three distinct generations and audiences are discernible in its literary structure.

Chapters Period Location Empire

1–39 Pre-exilic (late 8th BCE) Jerusalem Assyria

40–55 Exilic (mid-6th BCE) Babylon Babylon

56-66 Postexilic (late-6th BCE) Jerusalem Persia

Each of its pivotal chapters provides an indication of the section’s historical setting.

1–39 Pre-exilic setting. Exile predicted.

“in the days of Uzziah, Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah, kings of Judah” (Isa 1:1, NRSV)

“Days are coming when all that is in your house … shall be carried to Babylon” (Isa 39:6, NRSV).

40–55 Exile presupposed. Return predicted.

“Comfort, O comfort my people, says your God. Speak tenderly to Jerusalem, and cry to her that she has served her term, that her penalty is paid, that she has received from the LORD’s hand double for all her sins” (Isa 40:1–2, NRSV).

56–66 Postexilic setting. Return and Second temple presupposed.

“These I will bring to my holy mountain, and make them joyful in my house of prayer; their burnt offerings and their sacrifices will be accepted on my altar; for my house shall be called a house of prayer for all peoples” (Isa 56:7, NRSV).

Each of the kings listed in the book’s opening superscript (Isa 1:1) reigned in the late eighth century BCE of the pre-exilic period The chapter closing the first section predicts the impending exile to Babylon (Isa 39:6). When we flip the page to the next chapter, we are not simply waking up the next morning. We leapfrog some 150 years and awaken, not in Jerusalem, but in Babylon, where the exile is presupposed and its end with the return to the homeland is predicted (Isa 40:1–2). Instead of the threat of exile, we hear words of comfort to a people who have already received judgment from Yahweh’s hand. The motif of Yahweh’s effective prophetic “word” serves as a bookend marker to the opening and closing of the second section (Isa 40–55):

“The grass withers, the flower fades; but the word of our God will stand forever” (Isa 40:8, NRSV).

“For as the rain and the snow come down from heaven, and do not return there until they have watered the earth, making it bring forth and sprout, giving seed to the sower and bread to the eater, so shall my word be that goes out from my mouth; it shall not return to me empty, but it shall accomplish that which I purpose, and succeed in the thing for which I sent it” (Isa 55:10–11, NRSV).

The chapter opening the third section (Isa 56–66) presupposes the construction of the second temple, which was completed around 515 BCE, and thus points to the return home as predicted in the second section.

The book of Isaiah is unique among the Prophets considering its huge time span of roughly 230 years from Uzziah’s reign to the completion of the second temple (745–515 BCE), thus extending well beyond the lifetime of a single prophet and his generation. So why is the book of Isaiah exceptional with its inclusion of prophecies that span several generations? Debate about the book’s history of composition is complex. The essentials of that debate will be discussed in the module below concerning Isaiah 40–55. The book’s literary features, however, provide clearer clues regarding its thematic unity.

Attention to Yahweh and his relationship to Jerusalem/Zion is sustained throughout the book. A divine title characteristic of the book of Isaiah is “the Holy One of Israel,” which occurs 25 times throughout the book among each of its three sections. Outside Isaiah it occurs only in the Psalms (Pss 71:22; 78:41; 89:18) and in Jeremiah (Jer 50:29; 51:5; note 2 Kgs 19:22 = Isa 37:23). The book therefore focuses on the tension implicit in this divine epithet. Yahweh’s essential character is “holy,” as dramatized particularly in Isaiah’s vision (Isa 6:3), yet he has bound himself to “Israel,” who are perpetually “a people of unclean lips” (Isa 6:5). As a result, the book’s first section (Isa 1–39) focuses on the threatened judgment of the exile and the second on the promise of restoration (Isa 40–55). The third section (Isa 56–66) upholds these promises but makes explicit the conditions of repentance, which Israel has yet to demonstrate (e.g., cf. the promise of Isa 52:8–9 in the second section with the conditional promise of Isa 59:20 in the third section).

A thematic statement of the entire book might look something like this: a vision of the Holy One of Israel and Lord of the nations, who will exile the people of Zion because of their hard-heartedness (social injustice, insincere worship, and lack of faith, Isa 1-39) but will then create a new exodus returning them to Zion (Isa 40-55), while calling them to repent and summoning all peoples to worship him (Isa 56-66). The scope and literary shaping of the book of Isaiah discloses a theological message in its own right, namely that Yahweh’s narrative and plan for his people can take several generations to unfold—until its resolution begins to emerge. The Bible does not pretend that there are quick solutions, even from God, to issues of the human heart.

Isaiah 1–39. Isaiah and Micah are the first of the classical Prophets to preach in the southern kingdom of Judah. As both books contain oracles concerning Samaria and northern Israel, their ministries may have some overlap with those of Amos and Hosea to the northern kingdom (cf. the Judahite kings listed in their superscripts, Amos 1:1; Hos 1:1; Isa 1:1; Mic 1:1). As in each of these prophetic books of the late eighth century BCE, the empire of Assyria looms over the people of God.

Outline and Key Passages

[A revision of this section is underway and will be added when ready.]

Situation and Message: What’s at Stake?

Phase 1: Ritual and Social Critique (Uzziah’s reign, Isa 1–5)

Most of Isaiah’s oracles can be linked to four distinct episodes during his roughly 45-years of ministry.

Date Chapters Theme/Event

–742 1–5 Social criticism

735–733 6–9 Aram-Israel war

713–711 13–23 Ashdod rebellion

705–701 28–33; 36–39 Sennacherib’s invasion

While he may have delivered oracles on other occasions, the biblical evidence suggests that we should not imagine that he preached regularly to the people. Most notable is the 20-year gap in the middle. Rather, his oracles were occasioned by (i.e., delivered in response to) particular issues and events among the people of God. Once the Assyrian Empire begins to loom over the Levant on the second phase, most of Isaiah’s oracles touch on this threat.

Prior to the death of Uzziah (Isa 6:1), the oracles in Isaiah 1–5 focus on his ritual (esp. Isa 1:10–20) and social critique of the elites in particular (esp. Isa 5:1–7). Given these themes, he may have been influenced by his fellow Judahite, the prophet Amos. In chapter 1 his summons of the heavens and the earth (Isa 1:2 // Ps 50:1, 4), critique of Jerusalem’s ritual and social abuses (Isa 1:10–17 // Ps 50:7–20), and promise of reward for obedience (Isa 1:19 // Ps 81:13, 16, and Isa 1:18 // Ps 51:7) echo the language of these prophetic psalms. This resonance may suggest there was a closer connection between the prophets and the temple psalmists than we might have imagined.

The “Song of the Vineyard” (Isa 5:1–7) prompts the people of Jerusalem to “judge” for themselves what else Yahweh could do but to expose his people to ruin:

He hoped for justice (mishpat), but behold bloodshed (mispah).

for righteousness (tsedaqah) but behold outcry (tseaqah, Isa 5:7).

Yahweh’s judgment is not arbitrary, but reasonable. His expectations for his people are principally for their benefit, not his own.

Phase 2: Isaiah’s Memoirs and the Aram-Israel Coalition (Isa 6–12)

Tiglath-Pileser III Receiving Homage

Isaiah’s Vision (Isa 6). Shortly before King Uzziah’s death, Tiglath-pileser III (745-27 BCE) ascended the throne of Assyria and began to transform his localized kingdom into an empire that would stretch across the Fertile Crescent. In anticipation of the impending loss of political independence for both Israel and Judah, Isaiah is given his timely vision of “the Lord sitting upon the throne, exalted and lifted up” (Isa 6:1), whose sovereignty remains independent of political and military powers.

Because Isaiah 6:1–8:18 is unique within this prophetic book with its repeated use of first-person pronouns (I, me, my, esp. in Isa 6:1–13; 8:1–18), scholars have called it “Isaiah’s memoirs,” which also delimits a distinctive thematic unit. It begins with Isaiah’s extraordinary claims: “I saw the Lord” (Isa 6:1) and “the King, Yahweh of hosts my eyes have seen” (Isa 6:5). One may wonder how this squares with Yahweh’s counterclaim to Moses, “You are unable to see my face, for man cannot see me and live” (Exod 33:20). Isaiah, however, describes no details about God himself but simply “the hem of his robe filling the temple” and the “seraphim standing above.” This vision is a “type scene” of a divine council (cf. 1 Kgs 22:19–23; Pss 82:1–8; 89:5–8; Dan 7:9–10). In such a scene the presider “sits” and his attendants “stand above” the enthroned king. Micaiah’s vision is particularly analogous to Isaiah’s, wherein Yahweh asks the council whom he should send on a mission:

“I saw Yahweh sitting upon his throne and all the host of heaven standing above him on his right and on his left. And Yahweh said, ‘Who will …?’ … And he said …, ‘Go forth and do so’” (1 Kgs 22:19–20, 22).

In Isaiah’s vision the Lord asks, “whom shall I send, and who will go for us?,” the “us” referring to the divine council.

While both visions refer to the attendants as “hosts” (1 Kgs 22:19; Isa 6:3, 5), in Isaiah’s they are identified as “seraphim” or “burning ones.” Given the hints from other passages, they burn, not because they are on fire, but because they are “serpents” whose venom burns (Num 21:6, 8; Deut 8:15). The book of Isaiah elsewhere refers to the “flying serpent” (Isa 14:29; 30:6). In Isaiah’s vision they are apparently hybrid, otherworldly creatures, also sharing human characteristics (cf. Ezek 1:5, 8, 10), such as speech. They call out antiphonally,

“Holy, holy, holy is Yahweh of hosts,

the fullness of the earth is his glory” (Isa 6:3).

The threefold acclamation of Yahweh as “holy,” along with description of him as “king” “enthroned” and “exalted” are all terms that echo Psalm 99 (Ps 99:1–5, 9), which would have been sung by the Levitical choirs at the Jerusalem temple. These parallels are suggestive that Isaiah may have experienced this vision, not privately, but during a worship service at the temple, where he would have perceived—beyond the earthly symbols of antiphonal choirs and the “smoke” of sacrifice and incense—Yahweh’s heavenly temple-palace. In Israel and the ancient world the temple was not merely a symbol but a virtual portal to the heavenly court.

Once Isaiah’s “unclean lips” are “atoned,” Yahweh commissions him to go to “this people” (not my people):

Hear indeed but don’t understand;

see indeed but don’t perceive.

Make the heart of this people fat,

and their ears make dull

and their eyes smeared,

lest they see with their eyes,

and hear with their ears,

and their heart understand,

and turn and be healed (Isa 6:9-10).

Yahweh ironically commissions the prophet to a ministry of failure. Troubled, Isaiah’s response is to ask, “How long, O Lord?” Yahweh’s answer: until the exile of the land (Isa 6:11–13).

Info Box 17.: Ancient Translators Struggling with Theological Tensions

The Greek translators of the Septuagint apparently tried to soften the theological difficulties. Yahweh’s words shift from prescriptive commands to descriptive statements about the people’s condition.

‘You will hear by hearing and not understand; and although looking, you will look and not see.’ For the heart of this people has been thickened; and they have heard with difficulty with their ears, and they closed their eyes ⌊lest⌋ they see with their eyes and hear with their ears and understand with their heart and turn, and I will heal them (Lexham English Septuagint).

Given the repeated calls of Yahweh’s prophets for his people to hear, turn/repent, and experience forgiveness, how can we come to terms with this bizarre assignment? Clearly it is intended to have its shock value, but its resolution we will have to postpone until we consider the entire thematic unit of Isaiah’s memoirs.

The Aram-Israel Coalition (Isa 7–8). The next scene of his memoirs opens with “the house of David” hearing a rumor of conspiracy between the kingdoms of northern Israel, whose capital was in Samaria, and Aram, whose capital was in Damascus (Isa 7:2, 5–6). They planned to invade Judah, depose its king, Ahaz, and replace him with a puppet king. This plan was likely part of a larger plot to force Judah to join their coalition, so that together they would have a greater chance of freeing themselves from the grips of the Assyrian Empire. Understandably, Ahaz’s “heart … quivered like the trees of the forest quiver before the wind” (Isa 7:2). Through the prophet Yahweh offers him an oracle of salvation that the conspiracy will fail (Isa 7:7–9), but warns him and “the house of David” (Isa 7:2, 13),

If you (pl.) will not stand firm in faith (ta'aminu),

you (pl.) will not stand firm (te'amenu, Isa 7:9).

The prophet subtly alerts the king with an important word play on Yahweh’s original promise to David and his “house,” that is, his dynasty:

“Your house and your kingdom will stand firm (ne'man) before me forever;

your throne will be established forever” (2 Sam 7:16).

While not made explicit in the original promise, Isaiah clearly sees that the stability of the Davidic dynasty remains contingent on their faith in and faithfulness to Yahweh. To assure him further, Yahweh offers Ahaz “a sign.” The king responds with a seemingly pious answer, but Yahweh perceives his feigned piety (Isa 7:11–12).

2 Kings 16:5–9 informs us that Ahaz’s response to the Aram-Israel invasion was to appeal directly to Tiglath-pileser king of Assyria for rescue by offering to become “your servant,” that is, a vassal to the Assyrian empire. In addition, he sent “a gift/bribe” consisting of silver and gold from the temple and the palace. Tiglath-pileser obliged (2 Kgs 15:29).

In Isaiah’s memoirs Yahweh warns the prophet,

“Do not call conspiracy all that this people calls conspiracy, and do not fear what they fear and do not be in dread. Yahweh of hosts—him you shall regard as holy, and he will be your fear and he will be your dread” (Isa 7:12–13).

Perhaps counterintuitive to our culture, freedom from fear is possible only by fearing Yahweh. Fearing God means fearing nothing else. In this passage we perceive the effect of Isaiah’s vision of Yahweh as “holy.” Seeing Yahweh as “enthroned, exalted, and lifted up” (Isa 6:1) puts the Aram-Israel conspiracy of invasion—and all powers political and military—in true perspective. While the vision was Isaiah’s, its articulation in his memoirs is intended to make this vision of Yahweh above all powers accessible to all who read it. Hence they conclude:

Bind up the testimony, seal the teaching among my disciples. I will wait for the Lord, who is hiding his face from the house of Jacob, and I will hope in him. See, I and the children whom the Lord has given me are signs and portents in Israel from the Lord of hosts, who dwells on Mount Zion (Isa 8:16–18, NRSV).

He seals up this testimony as a sign to Israel that they have been duly warned who, in fact, they should fear—not kings and armies, but Yahweh of the heavenly hosts.

Hardening Hearts. Now that we have surveyed the thematic unit of Isaiah’s memoirs, we can return to the question of Yahweh’s problematic commission to harden the hearts of this people—until the exile. First, the means by which Isaiah hardens hearts is exemplified in king Ahaz. He does not preach doom and gloom, fire and brimstone, but offers him an oracle of salvation contingent on his faith in God. But knowing the recipient’s true character and pretend piety, Yahweh knows that Ahaz will reject his condition and thus his promise. Ahaz—in effect—hardens his heart to God’s offer of help.

Second, this commission was temporary. The Babylonian exile would mark the pivot in Israel’s ability to “hear, understand, and turn/repent.” This theme of repentance resurfaces in key passages throughout this prophetic book. “An altar call,” so to speak, closing the second section appeals to the exiles in Babylon to return:

Seek the Lord while he may be found,

call upon him while he is near;

let the wicked forsake their way,

and the unrighteous their thoughts;

let them return to the Lord, that he may have mercy on them,

and to our God, for he will abundantly pardon (Is 55:6–7, NRSV).

The third section then upholds the promises of salvation made in Isaiah 40–55 and significantly adds the condition of repentance:

And he will come to Zion as Redeemer,

to those in Jacob who turn from transgression, says the Lord (Is 59:20, NRSV).

Archaeology confirms that the exile was pivotal for Judah’s attitude towards idolatry and allegiance to Yahweh. During the pre-exilic period there were hundreds of idols found in Israel and Judah. But in the postexilic period where the Jews resettled, virtually no idols have been discovered (see Ephraim Stern, “Pagan Yahwism: The Folk Religion of Ancient Israel,” BAR 27:03 [May/June 2001]).

A century after Isaiah, Jeremiah said of Jerusalem’s so-called prophets and priests,

They have healed the wound/break (shever) of my people lightly,

saying, ‘Peace, peace,’

but there is no peace (Jer 6:14).

As the partial fracture of a bone may need a clean break before it can be reset and casted, it would seem that Yahweh’s commission of Isaiah looks beyond superficial repentance and “Band-Aid” solutions to a more systemic restoration of the people of God.

Messiah (Isa 9; 11). Linked by catchwords to Isaiah’s Memoirs (“teaching and testimony,” Isa 8:16 and 8:20, and the reversal of “darkness” and dawn, Isa 8:20, 22 and 9:2) but likely from some decades later, the addition of Isaiah 9 gives Judah hope for a new “David,” who will indeed exemplify the characteristics of Yahweh’s king. It is important to note that the book of Isaiah gives no indication that this promise of a new David is prompted by a change in the behavior of the people of God. It would seem that, after the recorded failure of Ahaz and David’s house, Yahweh graciously decrees a restoration of the Davidic monarchy on his own initiative, not because he is legally obliged.

The tribal territories of northern Israel that Tiglath-pileser III had annexed (cf. Isa 9:1 and 2 Kgs 15:29) in response to King Ahaz’s appeal for help (2 Kgs 19:5–9) are now given hope of glory and light in the form of a new Davidic king (Isa 9:1–7). The historical sequence of this passage points to Hezekiah as this new king. 2 Chronicles 30:1–11 confirms that Hezekiah had invited these northern territories to join the kingdom of Judah in celebration of Passover in Jerusalem. Isaiah’s oracle for the king’s coronation is phrased in Hebrew as a completed event:

For a child has been born to us,

a son has been given to us;

and the dominion has been upon his shoulder.

And his name has been called,

Wonder-Counselor, God-Warrior,

Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace.

Of the increase of his dominion and peace

there will be no end,

upon David’s throne and over his kingdom,

to establish it and support it

with justice and righteousness

from now to remote time.

The zeal of Yahweh of hosts will do this (Isa 9:6–7).

Although Christians typically associate these verses with Jesus Christ (encouraged by Handel’s “Messiah”), there is nothing in the language of this oracle that would be inappropriate for a human king of the Davidic dynasty (cf. Ps 2:7–8; 110:3; 89:19–29). As just noted, the primary audience for this message of hope, “the people walking in darkness,” live in the territories of northern Israel that were decimated by Tiglath-pileser III in the eighth century BCE.

Hezekiah was indeed a Davidic king celebrated in the Deuteronomistic history of 2 Kings (esp. 2 Kgs 18:1–9): “Yahweh was with him. Wherever he went out, he was successful. He rebelled against the king of Assyria and would not serve him” (2 Kgs 18:7). For a time at least, he fulfilled Isaiah’s promise by breaking “the yoke” of the Assyrian oppressor (Isa 9:3–5), whose army beat a hasty retreat home after they were “struck down” (2 Kgs 19:35–36). But in the end Hezekiah fell short of expectations in the views of both the Deuteronomistic historian (2 Kgs 20:12–19) and Isaiah himself (on Isa 28–33 see below).

As a result, Isaiah records another prophecy of a new David (Isa 11:1–6):

And a shoot shall come forth from the stump of Jesse,

and a branch from his roots will bear fruit.

Presupposed in this good news is the bad news that David’s family tree will be cut down. This “stump” may allude to the heavy territorial and monetary losses that Hezekiah ultimately incurred in 701 BCE when he rebelled against Assyria (2 Kgs 18:13–16). Another possible explanation for “the stump of Jesse” would be the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem in 587 BCE. In any case, Yahweh sevenfold “spirit” will rest upon some future, undisclosed Davidic “branch” (Isa 11:2; cf. Jer 23:5–6 = 33:15–16), whose reign will exemplify the “righteousness” and “justice” that should typify Davidic monarchs (Isa 11:3–5; 9:7; Jer 22:3, 15 23:5–6). Although a king typically “judges by” the evidence that “his eyes see” and by the testimony that “his ears hear”—both of which can be falsified—this king will judge by the superior sense: “and his smelling will be in the fear of Yahweh” (Isa 11:3, literally). He will indeed “smell out” the truth.

Phase 3: Oracles against the Nations (Isa 13–23)

The “oracles against the nations” in Isaiah 13–23 evidently form a generic collection (i.e., based on literary genre), not one based on historical chronology. The point of these oracles against the nations is, of course, not to forecast tomorrow’s “headlines” today, but to assure the people of Jerusalem that Yahweh ultimately reigns over the nations and will maintain his justice on behalf of his people. It is difficult for most modern readers to appreciate these assurances without sharing Judah’s experience of living under constant threat at the crossroads of neighboring nations and the superpowers of Mesopotamia and Egypt.

Ashdod Coalition against Assyria. Several of these oracles are linked to a second coalition of rebellion against the Assyrian Empire that arose 20 years later, this time instigated by the Philistine city of Ashdod (713–711 BCE, Isa 20:1–6). Its attempts were encouraged by the promise of Egyptian military support, whose 25th Dynasty at this time was Cushite (i.e., the people from Lower Egypt near modern-day Ethiopia). Both the Philistines and the Egyptians/Cushites sent ambassadors to persuade Hezekiah and the kingdom of Judah to join (Isa 14:28–32; 18:1–2). To grab the attention of his audience he engages in the symbolic act of “walking naked and barefoot” like a war captive, in order to illustrate the fate of those who put their trust in such political alliances against the Assyrian machinery (Isa 20:2–6).

By contrast, Isaiah preaches that Judah’s trust should lie in Yahweh, whose sanctuary rests on the sacred mountain of Zion:

What will one answer the messengers of the nation [Philistia]?

“The Lord has founded Zion,

and the needy among his people

will find refuge in her” (Isa 14:32, NRSV) .

At that time gifts will be brought to the Lord of hosts from a people tall and smooth, from a people feared near and far, a nation mighty and conquering, whose land the rivers divide, to Mount Zion, the place of the name of the Lord of hosts (Isa 18:7, NRSV).

Isaiah’s stance vis-à-vis political alliances is spelled out more fully in the fourth phase of his ministry, but here we may note that the first priority of God’s people should be to await Yahweh signal, when he will prune the Assyrian empire to size (Isa 18:3–6).

Other oracles can be linked to other events of Isaiah’s lifetime. Isaiah 17:1–14 is a judgment oracle on the Aram-Israel coalition (735–733 BCE), discussed above with Isaiah’s memoirs. Isaiah 14:24–27 announces Yahweh’s plans “to break the Assyrian in my land,” perhaps related to Sennacherib’s invasion in 701 BCE (discussed in the next section below).

Oracles against Babylon (Isa 13:1–22; 14:1–23; 21:1–10). Yahweh’s judgment on Babylon make sense in view their later destruction of Jerusalem in 587 BCE and exile of the Judahite population. Indeed, Isaiah 14:1–2 links the Israelites’ return to their homeland with Babylon’s overthrow. The reader should be mindful, however, that in Isaiah’s day Assyria was the superpower and Babylon was merely one of their vassals, along with Judah. Therefore, most scholars would date these oracles later to the period of the Neo-Babylonian Empire (626–539 BCE). The agents of Babylon’s destruction are identified as the Medes (Isa 13:17; 21:2), whose fierceness became known in their participation in the destruction of the Assyrian cities of Asshur (614 BCE) and Nineveh (612 BCE). The Medes, however, were later conquered by the Persian king Cyrus (550 BCE), who then took Babylon without a battle (539 BCE). The utter abandonment of Babylon as described in Isaiah 13:18–22 did not take place until after the death of Alexander the Great (323 BCE).

Phase 4: Hezekiah’s alliance with Egypt against Assyria (Isa 28–33; 36–37)

Isaiah 28–33. Linking the oracles in Isaiah 28–33 is the introductory formula “alas/woe” (Isa 28:1; 29:1, 15; 30:1; 31:1; 33:1)—a cry of lament originating in funeral ceremonies (1 Kgs 13:30; Jer 22:18; 34:5). As in the previous collection, not all of these oracles pertain to the same historical situation (e.g., Isa 28:1–6 likely relates to the earlier Aram-Israel coalition of 735–733 BCE).

Most reflect the fourth phase of Isaiah’s ministry focused on third coalition of rebellion against the Assyrian Empire, but this time the king of Judah, Hezekiah, was its champion. After the death of Sargon II in 705 BCE, widespread rebellion erupted throughout the Assyrian Empire. This was the opportune moment when the succession of power could be contested by rival princes and generals. Even if the transition were smooth, the new king would lack experience and the proven trust of all his officials. It would be four years before the Assyrian successor, Sennacherib, campaigned in the West to recover the rebellious provinces.

Key to Hezekiah’s coalition was an alliance with Egypt. Although Hezekiah is not named in any of Isaiah’s oracles (indeed “Hezekiah” appears only in the book’s superscript, Isa 1:1, and in the chapters lifted from the Deuteronomistic history, Isa 36–39), the prophet pronounces “the word of Yahweh” that soundly condemns “the rulers of this people in Jerusalem” for engaging in a “treaty” (28:14-15, 18; 30.1) with “Egypt” in order to improve their chances of rebelling against Assyria (see esp. Isa 30:1–3; 31:1–5). He faults this alliance for three reasons. (a) It is impractical (“Egypt’s help is worthless and empty,” Isa 30:7). (b) It is presumptuous, ignoring Judah’s theological priorities (“without asking for my counsel,” Isa 30:2, and they “do not look to the Holy One of Israel or enquire of Yahweh,” Isa 31:1). (c) It lacks vision of the God of Zion (“Yahweh of hosts will … fight upon Mt. Zion and … shield Jerusalem,” Isa 31:4-5).

Like a repeat from Isaiah’s memoirs (Isa 8:16–18), the prophet is instructed,

Now go, write it upon a tablet,

and upon a scroll inscribe it,

so it may become for the latter day a witness forever (Isa 30:8).

As before, he recognizes that his audience refuses his prophetic counsel, calling them “rebellious people” and “lying children” (Isa 30:9–11). Considering that Hezekiah must be counted among those who rejected Isaiah’s oracles, Isaiah 28–33 certainly provides an opposing perspective on this king who is so celebrated in the Deuteronomistic History (esp. 2 Kgs 18:3–7).

Isaiah 36–39. Additional Isaianic oracles have been transplanted to Isaiah 36–39 from the Deuteronomistic History (2 Kgs 18:13–20:19). To the Deuteronomistic material, Isaiah 38:9–20 adds a prayer of Hezekiah, but significantly Isaiah 36–39 omits the negative report in 2 Kgs 18:14–16, which records Hezekiah’s apology, submission, and payment of tribute to Sennacherib. Given the parallel in the book of Jeremiah, where a selection from the Deuteronomistic History (2 Kgs 24:18-25:30) is appended to the prophet’s own oracles (in Jer 52:1-34; note “Thus far are the words of Jeremiah,” Jer 51:64), it is likely that an earlier edition of the book of Isaiah concluded here and did not include Isaiah 40–66, which is addressed to later generations.

The Isaianic oracles contained in this appendix promise deliverance at the eleventh hour, as Sennacherib’s forces threaten the city of Jerusalem (Isa 36:6–7 = 2 Kgs 19:6–7; Isa 37:21–35 = 2 Kgs 19:20–34; also perhaps Isa 29:1–8). Yahweh assures the city:

“Therefore thus says the Lord concerning the king of Assyria: He shall not come into this city, shoot an arrow there, come before it with a shield, or cast up a siege ramp against it. By the way that he came, by the same he shall return; he shall not come into this city, says the Lord. For I will defend this city to save it, for my own sake and for the sake of my servant David” (Isa 37:33–35, NRSV).

Canonical and Theological Contribution

The most profound imprint of Isaiah 1–39 stems from his vision of “the Holy One of Israel.” Seeing Yahweh results in seeing nothing else quite the same. Fearing Yahweh means fearing no other power. Although the shadow of Assyria may darken the life of the people of God, Isaiah offers them a transcending vision of a higher power.

A comparison of the traditions that surface in the eighth-century prophets reveals some significant differences between northern Israel and the southern kingdom of Judah. Both Amos and Hosea refer to the early narrative traditions of the exodus, wilderness, and the conquest period—also foregrounded in the Pentateuch. Hosea includes the Sinai covenant as well. Isaiah, on the other hand, makes no reference to these Moses traditions. Instead, he foregrounds the two traditions native to his own Jerusalem. The Zion tradition affirms this local mountain as Yahweh’s sacred mountain. As he dwells in Zion, he will protect it. The David tradition affirms his choice of this dynasty, by which he will establish righteousness and justice.

We would greatly misunderstand Isaiah, however, if we took him to be an establishment prophet. His vision of Yahweh made that impossible. The institutions of the elite would always be subject to the critique of the higher Sovereign. While his later prophecies (Isa 36–37) affirm the inviolability of Zion, his earlier prophecies consistently fault the people and their leaders for failing to trust the God of Zion and for choosing the political expedient. His model portraits of the messianic David brought to light the shortcomings of his contemporary Davidic kings. Without trust in Yahweh of hosts, their institutions of government and religion would do them little good. Yahweh values faith in him over political powers, and the practice of justice over mere religious ritual.