Pentateuch

Formation and Themes of the Pentateuch

Torah and Narrative

► The Hebrew Bible identifies the Pentateuch as Torah, traditionally translated "Law," but the prevailing genre of Torah is narrative.

The Hebrew Bible identifies the first five books of the Bible as Torah, which is a Hebrew word that means “teaching” or “instruction.” This label is perhaps best exemplified when Ezra, “a scribe skilled in the Torah of Moses” (Ezra 7:6), read “the book of the Torah of Moses” to the early postexilic community in Jerusalem (Neh 8:1, 14). Most English translations have rendered the Hebrew word “torah” as “law.” This choice has the unfortunate consequence of inclining most readers to characterize the Pentateuch as legal material. For Christians in particular the word law tends to have negative connotations, especially when juxtaposed with the word grace.

Nevertheless, even English translations are clear that the prevailing literary genre in the Torah is narrative—more so than law. The principal means by which God “teaches” his people is through narrative. Indeed, much of the Old Testament/Hebrew Bible itself is packaged as narrative (Joshua–Esther), as also the New Testament (Matthew–Acts). Yet Christian churches tend to formulate their beliefs in theological doctrine. Denominations construct “a statement of faith”; sermons tend to have a three-point outline; Sunday schools teach a particular lesson or virtue. So, why is narrative retelling Israel’s preferred mode of divine revelation? Before we probe the nature and purpose of biblical narrative, we must first ask, why is narrative the dominant genre in the Hebrew Scriptures, the record of God’s revelation?

► The default genres for theology in the ANE were myths and epics, but the OT presents Yahweh primarily through "historical" narrative.

Narrating a deity’s encounters with a particular people/nation is certainly not the default mode of ancient Near Eastern religions. Ancient Near Eastern theology can be characterized as “naming the powers.” As most folk supported their lives through farming and shepherding, the key factor necessary for survival but beyond their control was the weather. Hence, the god of the skies, whose reign was evident in the rain, tended to be their most popular deity. The gods of the sea, sun, moon, earth, abyss, and grain were among the supporting cast. While their powers were manifest in nature, they were comprehended in anthropomorphic (i.e., human) form and particularly as royal figures. Hence, cult statues or idols facilitated their worship. Their houses or palaces/temples were located at their urban centers, especially their capitals. Their stories took the form of narrative poetry. First, there were myths, which were stories about the gods (the Baal Myth at Ugarit, the Eridu Genesis and Enuma Elish in Mesopotamia). Second, there were epics, which were stories about the gods’ encounters with kings, priests, and sages primarily (e.g., Kirta and Aqhat at Ugarit, and Gilgamesh, Atrahasis, and Adapa in Mesopotamia). These stories tend to be “larger-than-life” and set in primeval times, not in the course of historical events. Ancient Near Eastern peoples certainly composed historical chronicles and annals, but their purpose was principally to glorify the military victories and building projects of particular kings, not to serve as a canonical text for their religion.

The oldest accounts in the OT appear to be archaic poems: “the Song of the Sea” (Exod 15:1–18) and “the Song of Deborah” (Judg 5:2–31)—both victory songs, and the “Blessing of Jacob” (Gen 49:2–27) and the “Blessing of Moses” (Deut 33:2–29), among others. As in the ANE, they are poetic and feature Yahweh as the God of the skies (Exod 15:8, 10; Judg 5:4–5; and Deut 33:2, 26; cf. Gen 49:24–25). But their attention is focused on God’s interactions with a people’s events and their historic opponents, not against cosmic forces/gods or on behalf of an elite individual set in primeval times. After Israelite culture shifts from song-singers to scribes, their preferred genre became that of narrative prose. Genesis 12–50 consists of family narratives telling of the encounters between the God of the clan and the ancestors, Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebekah, and Jacob and Rachel. He speaks, promises, and blesses. In Exodus, Yahweh fights for and liberates his kindred people. According to these accounts, Yahweh came to Israel’s awareness in the social and historical experiences of the social unit of the family and people.

The ancient Israelites did not look for Yahweh primarily in the cosmic powers in the realm of nature and its seasonal cycles. Yahweh encountered the Israelites through their family stories and national history. Like other ancient Near Easterners, the Israelites were interested in blessing, but it came as one bestowed by their loyal, patron deity. Israel’s purpose for composing historical narrative stems from their theology of Yahweh. They preserve these ancient accounts and continued to tell them because they were viewed as windows into Yahweh’s character and his ways of interacting with his people.

Info Box: Where and how do you expect to encounter God?

This is a fundamental question of religion. Do you look for the divine in the powers of nature? In (military) victory or success (blessing)? In a dramatic intervention or a dialogical interaction? In ritual and sacrament? In a morality of good and evil? In the rewards and punishments of justice? In a conversion experience? In mysticism? In personal intimacy? The answers to these questions would certainly vary among the social groups represented in ancient Israel: farmers and pastoralists, kings and generals, priests and scribes, historians and prophets, and landowners and peasants. The same variety would be evident among the various denominations within Judaism and Christianity.

Torah as Contemporized Historical Narrative (Deuteronomy)

► Deuteronomy exemplifies how events of the past were "contemporized" so that readers could imaginatively enter into the narratives as participants.

We can gain further insight into how narratives and laws of the past function as “instruction” for present-day readers by examining cases where earlier narratives and laws are retold for later generations. Synoptic accounts (e.g., the NT Gospels) can bring to light how past traditions are updated and applied to later generations. As already noted, the book of Deuteronomy, as its name implies, is a second (deutero-) telling of the law (nomion, cf. Deut 17:18). Deuteronomy retells and reinterprets some of the laws found in the book of Exodus (e.g., the Tenth Commandment and the Hebrew slave laws). The three Mosaic sermons that comprise the book of Deuteronomy also re-enact Yahweh’s “cutting” the covenant with subsequent generations.

Yahweh our God cut with us a covenant at Horeb. Not with our ancestors did Yahweh cut this covenant, but with us, those of us here today, all of us who are alive. Face to face Yahweh spoke with you at the mountain from the midst of the fire (I was standing between Yahweh and you at that time to declare to you Yahweh’s word, for you were afraid because of the fire and did not go up the mountain), saying … (Deut 5:2–5)

Although this sermon is clearly addressed to second-generation Israel, whose parents were the actual witnesses of the Sinai/Horeb covenant but perished in the wilderness, Moses addresses them as though they were the actual participants in the covenant ceremony. By so doing, each generation who hears/reads the book of Deuteronomy is encouraged to imagine themselves as actual participants at the Sinai covenant ceremony, face-to-face with Yahweh as it were. In effect, the book of Deuteronomy is contemporized history, where a later generation is imaginatively made contemporary to an earlier generation who actually witnessed and participated in events with Yahweh.

Immediately after the pronouncement of the covenant blessings and curses (Deut 28:1–68), which conclude the actual covenant document from Horeb (Deut 5:1-28:68), Yahweh curiously commands Moses to cut another covenant “in the land of Moab, besides the covenant that he cut with them at Horeb” (Deut 29:1).

You are standing today, all of you, before Yahweh your God … so you may enter into the covenant of Yahweh your God and into his oath that Yahweh your God is cutting with you today, in order that he may establish you today as his people and that he may be your God as he spoke to you and as for to your ancestors, to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob. Not with you yourselves alone am I cutting this covenant and this oath, but with him standing here with us today before Yahweh our God and with him who is not here with us today (Deut 29:10–15).

Again, Moses speaks to his audience imaginatively as though they themselves had witnessed Yahweh’s deeds in Egypt (“you have seen … before your eyes,” Deut 29:2), even though they are explicitly second-generation Israel living after the “forty years in the wilderness” (Deut 29:5). But this Moab covenant deliberately goes one step beyond the Horeb covenant: it includes anyone who is not part of this Deuteronomic audience. The “today” contemporary with the Moab covenant becomes merged with the “today” of every subsequent generation.

This imaginative contemporization of history is particularly evident in the ritual offering of the firstfruits of the farmers harvest (Deut 26:1–3), where the “them” and “us” distinction is blurred. Here the worshiper—any worshiper of any generation—is to imagine himself or herself as an actual participant in the events of the exodus generation and the subsequent settlement generation.

When the priest takes the basket from your hand and sets it down before the altar of the Lord your God, you shall make this response before the Lord your God: “A wandering Aramean was my ancestor; he went down into Egypt and lived there as an alien, few in number, and there he became a great nation, mighty and populous. When the Egyptians treated us harshly and afflicted us, by imposing hard labor on us, we cried to the Lord, the God of our ancestors; the Lord heard our voice and saw our affliction, our toil, and our oppression. The Lord brought us out of Egypt with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm, with a terrifying display of power, and with signs and wonders; and he brought us into this place and gave us this land, a land flowing with milk and honey. So now I bring the first of the fruit of the ground that you, O Lord, have given me.” You shall set it down before the Lord your God and bow down before the Lord your God. (Deut 26:4–10, NRSV)

While Deuteronomy is the book most explicitly identified as torah/teaching (Deut 1:5; 4:44; 17:18; 31:9–11, 24–26), the entire Pentateuch is later identified as “the Torah of Moses” (Ezra 7:6; Neh 8:1, 14). The Pentateuch tells history not for its own sake, to record or document the past, but to provide religious and theological “instruction” for succeeding generations in the believing communities. Thus, in the Ancestral Narratives (Gen 12–50) we, as the implied readers, are meant to walk in the footsteps of our forebears, Abraham and Sarah. In Exodus 1–18 we suffer in Egypt and celebrate God’s liberation. In Exodus 19–40 we stand at Sinai before God. In Deuteronomy we hear Moses’ sermons and reenact the covenant.

Info Box: Deuteronomic Distinctives and the Deuteronomistic History

Simply put, the book of Deuteronomy is about

One God

One Sanctuary

One Covenant

Framed as a covenant/treaty document, it stipulates the vassal’s exclusive loyalty to its overlord, that is, Israel’s loyalty to Yahweh their God. Hence, any devotion to other gods and their idols is considered treason. The one God is symbolized in the single sanctuary and altar, thus eliminating the possibility of “high places.” Peculiar to Deuteronomistic literature is the identification of the temple as the dwelling place for Yahweh’s “name” (Deut 12:11; 1 Kgs 8:20, 27). As the Sovereign over an empire, he places his name there, but his principal residence is not in the vassal’s territory. Rather, Yahweh’s “habitation” is in “the heavens/skies” (Deut 26:15; cf. 4:36, 39; 33:26). The essential components of the covenant/treaty are the stipulations imposed on the vassal, followed by the blessings and curses. The outcome will be determined by the vassal’s choice to comply or not comply (see esp. Deut 30:15, 19).

Because the historical books that follow Deuteronomy reflect its distinctive terminology and theology, these books can be described as the "Deuteronomistic History": Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, 1-2 Samuel, and 1-2 Kings. These historical books contain tests of whether or not Israel will obey and enjoy the blessings or disobey and suffer the curses. At the end of the book of Joshua the controversial altar constructed by the Transjordan tribes is strikingly reinterpreted, not as an altar for sacrifices, but simply as a “witness” between the Transjordan and Cisjordan tribes (Josh 22:26–28, 34). The book of Judges is set up as Yahweh’s “test” to see if they will walk in his way or not, while living among the Canaanite people groups (Judg 2:21–3:6). The review of each of the kings of Israel and Judah in 1–2 Kings includes a “report card.” Whether they pass by “doing what was right” or fail by “doing what was evil” is largely determined by their support or lack thereof for the central sanctuary in Jerusalem.

Torah as Recasted Historical Narrative (1–2 Chronicles)

► Although Sam-Kgs and Chronicles are synoptic accounts, the Deuterononmistic History ends in the exile and so focuses on a sin-judgment pattern. The Chronicler's History concludes with the postexilic restoration and so focuses on an obedience-blessing pattern and recasts the characters and events.

A side-by-side comparison of Samuel–Kings and 1–2 Chronicles shows that most of the material is word-for-word identical. Why should the Bible bother to repeat itself? And, how does the later author-editor use his earlier biblical source? What literary conventions were considered “kosher” for biblical narrators? The only way to answer these questions is to engage in a close reading of the texts. We will discover that the smallest of textual changes can reflect profound theological developments and lessons.

Before looking at details, we need to consider the wider picture of why these historical panoramas were written. What were their thematic purposes? Samuel–Kings is part of a larger literary corpus called the Deuteronomistic History: Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, 1–2 Samuel, and 1–2 Kings. Joshua, Judges, and 1–2 Kings in particular resonate with the terminology and theological distinctiveness of the book of Deuteronomy.

The Deuteronomistic History ends with Judah living in the Babylonian exile. Why are the people of God living in exile, alienated from their land and without king and temple? From this historical standpoint we can understand this history’s recurring themes of human disobedience and divine judgment. In fact, the Deuteronomic curses climax with threats of an invading nation, who will besiege and then scatter the Israelites “among all peoples” (Deut 28:49, 52, 64). Thus, the Deuteronomistic history highlights Israel’s failure to comply stipulations of Yahweh’s covenant, documented in the book of Deuteronomy. In light of the terms of the contract, Yahweh’s judgment was just.

Although the Chronicler’s history covers the same historical period as Samuel–Kings, it goes one step further by concluding with the decree of the Persian king, Cyrus the Great.

In the first year of King Cyrus of Persia, in fulfillment of the word of the Lord spoken by Jeremiah, the Lord stirred up the spirit of King Cyrus of Persia so that he sent a herald throughout all his kingdom and also declared in a written edict: “Thus says King Cyrus of Persia: The Lord, the God of heaven, has given me all the kingdoms of the earth, and he has charged me to build him a house at Jerusalem, which is in Judah. Whoever is among you of all his people, may the Lord his God be with him! Let him go up” (2 Chr 36:22–23, NRSV).

From this historical standpoint the exile is now behind the people of God. What is critical in this new chapter of their history is their return to the land and the restoration of their temple. The question facing the Chronicler and his audience is the reverse of the Deuteronomistic History: how can we obtain God’s blessing? He retells the history of Israel’s monarchy to illustrate acts of human obedience that lead to divine blessing.

Info Box: Whose house and whose kingdom? (2 Sam 7:16 // 1 Chr 17:14)

One of the most important OT passages is the Dynastic Oracle in 1 Samuel 7, which hinges on a word play with “house.” Because David now lives in a “house,” that is, a royal palace (2 Sam 7:1–2), he desires to build for Yahweh a “house,” that is, a palace/temple (2 Sam 7:5–7, 13). Yahweh, not to be out-given, promises to build for David “house,” that is, a royal household/dynasty (2 Sam 7:11, 16). The Chronicler renders the climactic, closing verse differently than that found in 2 Samuel.

“Your house and your kingdom (mamlakah) shall be steadfast to remote time before me; your throne will be established to remote time” (2 Sam 7:16).

“I will station him in my house and in my kingdom (malcût) to remote time; and his throne will be established to remote time” (1 Chr 17:14).

The textual changes are slight (including an updating of how "kingdom" is spelled), but the meaning is profoundly altered. The promise no longer concerns David’s house and David’s kingdom, but Yahweh’s house and Yahweh’s kingdom. Although one might infer that the promise of permanence shifts from David’s house/dynasty to Yahweh’s house/temple, but the phrase joined with “and” is a figure of speech called hendiadys, whereby conjoined nouns (i.e., house and king), actually denote a noun modified by an adjective (i.e., a royal house). The promised shifts from David’s royal dynasty to Yahweh’s. Thus, the Chronicler radically re-signifies how “kingdom” is to be understood in the postexilic period: Israel is no longer to focus on the geopolitical kingdom of the Davidic dynasty, but on Yahweh’s transcendent kingdom. It is the Chronicler who uniquely clarifies to whom the kingdom ultimately belongs. Solomon will “sit on the throne of the kingdom of Yahweh over Israel” (1 Chr 28:5; cf. 29:23). It is “the kingdom of Yahweh in the hand of the sons of David” (2 Chr 13:8). Hence, the first psalms to mention Yahweh’s “kingdom” are postexilic (Ps 103:19; 145:11–13).

What is remarkable is that the Chronicler would edit divine speech, the words of God. Why would he do so? Since 2 Samuel 7 was first composed, David’s kingdom collapsed under the weight of the Babylonian invasion in 587 BCE. One might be tempted to explain this failure on the basis of the continued disobedience of David’s successors (i.e., the interpretation found in the Deuteronomistic history), but even the Chronicler retains the key promise, “My loyalty I will not remove from him as I removed it from the one who was before you” (i.e., Saul, 1 Chr 7:13 // 2 Sam 7:15). Instead, the Chronicler likely engaged in exegesis of his primary text, 2 Samuel 7. The second half of the chapter contains a prayer of David, wherein he acknowledges that Israel is “your people” (not David’s) and that “Yahweh of hosts is God over Israel” (2 Sam 7:24–26). David is simply “your servant.” Thus, David is merely a vice-regent under Yahweh. David’s kingdom is ultimately Yahweh’s kingdom. In this sense, one could argue that while the Chronicler does not accurately transmit the actual words of God, he more accurately interprets the theology implicit in those words.

Info Box: David brings the ark into Jerusalem (2 Sam 5:17–6:15 // 1 Chr 13–16)

David did not have an easy road to the throne over the kingdom of Israel. The natural successor to king Saul would be a son of Saul. Such was the thinking of Saul’s commander-in-chief, Abner, who had one of Saul’s sons, Ish-bosheth (Esh-baal in 1 Chr 8:33; 9:39) installed as king over the northern tribes of Israel (1 Sam 2:8–10). At first David was king over only Judah (2 Sam 2:1–4, 11). After several incidents of political intrigue, Ish-bosheth is assassinated and David becomes king over all Israel (2 Sam 4–5). Next, he needs a capital city. If he chooses one in the territory of his tribe Judah, the Northerners will accuse him of showing favoritism. If he chooses one in the north, his own tribe will feel betrayed. Thus, he shrewdly decides on a neutral city, Jebus/Jerusalem, near the border of the northern tribe of Benjamin and the southern tribe of Judah. David and his men capture the portion of Jerusalem that is called “the Stronghold of Zion,” which he (humbly) renames “the City of David” (2 Sam 5:7–9). Having made it his political capital, he seems intent to make it his religious capital, by bringing the ark of the covenant there.

He attempts to do so by transporting it on an ox cart, but when the oxen stumble, the ark begins to tumble (2 Sam 6:1–11). A man named Uzzah reaches out to stabilize it, but God strikes him down. David was both angry and afraid and so aborts the mission. He deposits the ark at “the house of Obed-Edom the Gittite.” Three months later,

“It was told to king David, ‘Yahweh is blessed the house of Obed-Edom and all that belongs to him on account of the ark of God’” (2 Sam 6:12a).

This news is apparently what motivated David to make a second dangerous attempt. The narrator tells us,

“When the bearers of the ark of Yahweh had marched six steps, he sacrificed an ox and a fatling” (2 Sam 6:13).

The animal pair that David sacrifices in the 2 Samuel account, an ox and a fatling, is unattested, and therefore unsanctioned, in priestly literature. Outside the Bible, these animals are a regular favorite food of the gods in the Ugaritic texts (KTU 1.1:4:31; 1.3:4:41–42; 1.4:5:45; 1.4:6:40–42; 1.22:1:12–13).

The Chronicler tells a very different story and recasts David, not as an opportunist, but as a pious Jew. First, he changes the chronological order of events. After David’s first attempt to bring the ark into Jerusalem, he transposes the earlier account in 2 Samuel 5:17–25 (// 1 Chr 14:8–16), where David twice defeats the Philistines. Each time he “inquired of Yahweh” (2 Sam 5:19, 23 // 1 Chr 14:10, 14). In 1–2 Samuel, he apparently does so by means of the priestly ephod (1 Sam 23:1–2; 30:7–8). This means of divining the divine will is not mentioned in 1–2 Chronicles. The Chronicler by transposing sequence of events gives David access to the ark of the covenant before he needs to inquire of Yahweh in his defeat of the Philistines. According to the Priestly strand in the Pentateuch (P), the ark is the preferred means of divine communication (Exod 25:22; Num 7:89).

Second, the Chronicler alters David’s motivation for the second attempt to bring the ark into Jerusalem. He omits the report that the household retaining the ark of the covenant for three months has been blessed (2 Sam 6:12a). Instead, the Chronicler inserts 24 verses of material that carefully distinguishes the respective roles of the priestly sons of Aaron and the Levites, who are charged with carrying the ark. David says,

“because from the first time you did not (bring up the ark) Yahweh our God made an outburst against us because we did not seek him according to the judgment” (1 Chr 15:13).

The narrator then tells us,

“the Levites carried the ark of God, as Moses commanded according to the word of Yahweh, with the carrying poles upon their shoulders” (1 Chr 15:15).

So, in the Chronicler’s account what motivates David to make the second attempt is not a report that the retainer of the ark has been blessed; David becomes motivated once he consults his Bible (rather than an oracular word). In the books of Moses he discovers the instructions for how the ark is to be transported.

Third, the frequency and the animals sacrificed is changed. Instead of the tedious process of sacrificing every six paces, there is only one instance at the journey’s conclusion:

“When God helped the Levites, the bearers of the ark of the covenant of Yahweh, they sacrificed seven bulls and seven rams” (1 Chr 15:26).

The animals the David sacrifices in the Chronicler’s account, along with the sacred number seven, have plenty of biblical precedents in the Bible (e.g., Ezek 45:23; 2 Chr 29:21; cf. Num 23:1, 4; Job 42:8).

Fourth, while David is “skillful in playing the lyre” in 1–2 Samuel (1 Sam 16:16–18, 23; 18:10; 19:9), in 1–2 Chronicles he is the chief architect behind the Levitical choirs, their musical instruments, and their singing of psalms (1 Chr 15:16; 16:4, 7, etc.). Most significantly, the Chronicler inserts a lengthy psalm, performed at David’s initiative (1 Chr 16:7–36). It is actually drawn from three separate psalms of three distinct literary genres (1 Chr 16:8–22 = Ps 105:1–15, which is a portion of a lengthy historical hymn; 1 Chr 16:23–33 = Ps 96:1–13, a psalm of Yahweh’s kingship; 1 Chr 16:34–36 = Ps 106:1, 47–48, which quotes the opening line of a lengthy historical corporate lament and the doxology that closes Book IV of the Psalter). Although these psalms clearly postdate David’s generation, the Chronicler removed anachronistic references to the temple and its courts (cf. Ps 96:6, 8 and 1 Chr 16:27, 29, where “his sanctuary” is replaced with “his place” and “into his courts” is replaced with “before him”).

► To provide his postexilic audience with guidance on obedience that leads to blessing, the Chronicler recasts David as an exemplar of Jewish piety.

Given the new situation and opportunity facing the Chronicler’s audience, that is, the possibility of the return and restoration of the people of God and their temple in the land, it would do them little good simply to rehearse the narrative in Samuel-Kings merely for the sake of historical precision. Simply reiterating the patterns of human disobedience and divine punishment for the postexilic audience would offer little encouragement and guidance. Rather, he uses the familiar historical characters and events and recasts them as models of obedience to offer helpful lessons for obtaining God’s blessings. For the sake of contemporary readers, the Chronicler’s “David” does what should be done, not what David actually did. He recasts David as an exemplar of piety and patron of psalmody.

The biblical canon thus presents readers with two contrasting portrayals of David: the opportunist in 1–2 Samuel and the exemplar of Jewish piety in 1 Chronicles. In this respect, readers can hear God’s revelation in “stereo,” so to speak. If one needs guidance on godly living, than the David of 1 Chronicles would be the more helpful model. But if this were the sole portrayal in the Bible, the reader could become discouraged, as we all make mistakes and fall short. So, if one needs assurance that God forgives sinners and enables them to continue as his agents, then the David of 1–2 Samuel would be the more helpful model.

Our side-by-side comparison of the Deuteronomistic History in Samuel-Kings and the Chronicler’s history illustrates that biblical writers could use older narratives as vehicles for new theological developments. In fact, retelling familiar biblical narrative and overlaying it with later theological interpretation and contemporary application was a preferred genre in Second Temple Jewish literature, as evidenced by 1 Enoch 6–11, Jubilees, Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs, Pseudo-Philo’s Biblical Antiquities, Josephus’s Jewish Antiquities, and the Genesis Apocryphon found at Qumran (scholars have termed this “rewritten Bible”).

► The past is retold for present-day meaning, identity, and issues—thus creating a new "memory."

This technique is not unlike contemporary preaching, where the pastor attempts to apply biblical passages by using biblical characters and stories as types for modern day audiences to interpret their own experiences. In this respect, we can understand biblical narrative as “preached history,” wherein it does indeed refer to historical events but recasts those events and their characters in order to convey contemporary meaning. The past is not told for its own sake as history; the past is retold for present-day meaning, identity, and issues. Historical narrative in the Bible is “contemporized memory” (what scholars call collective/social memory). Figures and events remain constant, but speeches, details, and sequences can be adapted to convey a new theological torah/teaching. Historical precision is secondary. Instead, the biblical characters and events are viewed as literary “types” or models that are malleable for the sake of theological and pastoral torah/instruction. The “outlines” of biblical stories are maintained and foregrounded, while the details of biblical stories can recede. What is critical in narrative torah is not the singular, particularities of history, that is, the one-time happenings of the past. Rather, the figures and events of the past are viewed as a window/type of how God and his people interact. Biblical narrative establishes continuity with the past and the traditions of the forebears, but also presents the newness that the people of God discover in their ongoing pilgrimage with Yahweh.

The Pentateuch as a “Mosaic”

► The use of the phrase "to this day" in the Pentateuch implies its original audience lived in the monarchic period.

Before examining what kind of a composition the Pentateuch is, it has been helpful to compare and contrast the synoptic accounts of the Old Testament, namely Samuel–Kings and 1–2 Chronicles. Here we can see in existing documents (apart from hypothesized sources) how a later biblical writer, the Chronicler, edited an earlier document for his own literary and theological purposes. The Chronicler’s history and the Pentateuch share the same phenomena, but the presentation is different. While the Chronicler compiles a separate scroll, in the Pentateuch each compiler’s work was woven into a single scroll.

As we approach the Pentateuch, our first question ought to be, how is it meant to be read as “teaching”? Before we pose our own theological, religious, historical or social questions, we must first ascertain an appropriate reading strategy—so that we can read it respectfully on its own terms. Anyone who has been misunderstood recognizes the importance of interpreting a text in its context. So, what is the historical and social context of the Pentateuch’s audience? From what vantage point does the author compose and shape the Pentateuch?

We can find a clue where the readership is situated in Israel’s history by examining the phrase, “to this day,” which recurs in Genesis and Deuteronomy referring to a past circumstance that still exists in the generation of the narrator. In short, “this day” points to the time period when Israel is settled in the land of Canaan, sometime between the Judges period and the Babylonian exile (1200–586 BCE). When the narrator reminds his readers in the Abraham narrative, “at that time the Canaanites were in the land” (Gen 12:6; 13:7), it is clear that they currently have no Canaanite neighbors. Two other passages of Genesis point more specifically to the monarchic period (1000-586 BCE): one presupposes the Israelite monarchy (Gen 36:31) and another the sanctuary on Mount Zion/Moriah (Gen 22:14). While the traditions underlying the Pentateuch are no doubt ancient, it was put to writing for the benefit of the Israelites living in the monarchic period.

Info Box: “ … to this day”

In Genesis the phrase points to the existence of people groups neighboring Israel (Moabites and Ammonites, Gen 19:37–38), place names (Beersheba, Gen 26:33), social customs (Gen 32:33; 47:26), and Rachel’s tomb (Gen 35:20). In Deuteronomy it refers to the Edomites (Deut 2:22), place names (Deut 3:14), the role of the Levites (including bearing the ark, which points to a date prior to the Babylonian destruction of the temple in 587 BCE, Deut 10:8), the destruction of Egyptian hegemony over the land of Canaan (Deut 11:4), and the location of Moses’ tomb (Deut 34:6).

► Should we read the Pentateuch as an authored composition or an edited one?

Another question essential to our reading strategy lies in the basic literary question concerning genre. We must ask, what kind of a composition is the Pentateuch? To answer this we must consider how it was composed. Was it authored by an individual with a coherent story line and theme? Or was it compiled by a series of authors and editors with a variety of storylines and themes? Our reading strategy must be appropriate to the kind of literature we attempt to read. The clearest approach is an empirical one. Simply put, if we attempt a close reading of the Pentateuch as a coherent composition written from a singular point of view, we will quickly become puzzled readers. This is not to say the Pentateuch is full of contradictions and therefore bad literature. It is only to say that we have assumed an improper reading strategy. But if we are open the possibility—as respectful readers should be with ancient literature—that the Pentateuch is a tapestry woven together through centuries of oral tradition, scribal documents, and editorial compilations, we may discover a grand metanarrative that is more than the sum of its parts.

Info Box: Did Moses write the Pentateuch?

Genesis–Numbers nowhere identify their author(s). They do occasionally mention that “Moses wrote” things down, but in context these verses indicate the exception, not the rule. He writes a brief verse account of Yahweh’s war with the Amalekites (Exod 17:14–16), “the Book of the Covenant” (Exod 24:3–7 referring to Exod 20:22–23:33), a second Sinai covenant (Exod 34:27–28 referring to Exod 34:10–26), and a record of the geographic locations of the wilderness journeys (Num 33:2 referring to Num 33:1–49).

The Psalms and the Prophets refer to Moses as Israel’s leader (often alongside Aaron) during the exodus period (Pss 77:20; 105:26; Isa 63:11–12; Mic 6:4), but they do not associate him with a body of legal or narrative material, let alone as author of the Pentateuch.

The Deuteronomistic History (i.e., the books of Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, 1–2 Samuel, 1–2 Kings) uses several equivalent expressions to refer to “(the book of) the law of Moses” (Josh 1:7–8; 8:30–35; 23:6; 1 Kgs 2:3; 2 Kgs 14:6 = 2 Chr 25:4; 2 Kgs 23:25) or “the law that Moses commanded” (Josh 1:7; 22:5; 2 Kgs 21:8). It should be no surprise that the allusions in these passages echo the book of Deuteronomy in particular, not the other books of the Pentateuch. This is especially evident where there is explicit citation. Joshua 8:31 derives from Deut 27:5–6 (“… an altar of stones. You shall not wield upon them iron. With whole stones you shall build the altar of Yahweh your God”), not from Exod 20:25 (“But if an altar of stones you make for me, you shall not build them with an ashlar, or if you wield your sword upon it, you would profane it”). Both Deut 27 and Josh 8 concern the altar to be built on Mount Ebal. 2 Kings 14:6 explicitly quotes Deuteronomy 24: 16. As such, these references to passages in “the law of Moses,” or the book of Deuteronomy as we now call it, are simply that: they are references to Deuteronomic passages; their point is not to assert Mosaic authorship or copyright.

Although the book of Deuteronomy is clearly presented as Moses’ oral “words” spoken to the Israelites (in three “sermons”: Deut 1:1–5; 4:44–5:1; 29:1–2), chapter 31 is the first to mention Moses “writing” “this law” (Deut 31:9–11), that is, the “Book of the Law,” which is to be deposited beside the ark of the covenant (Deut 31:24–26). This same chapter also ascribes a song to Moses (Deut 31:19, 22 referring to Deut 32:1–43).

The postexilic books refer to “the Book” and/or “the Law” “of Moses” or “(of Yahweh) by the hand of Moses” (2 Chr 23:18; 30:16; 33:8; 34:14–15; 35:12; Ezra 3:2; 6:18; 7:6; Neh 8:1, 14–15; 10:29; 13:1–2; Dan 9:11, 13; Mal 4:4). These passages allude to verses in Deuteronomy and also to ritual texts in Leviticus and Numbers especially. 2 Chr 30:16 mentions the ritual of “throwing blood” as the prerogative of priests (Lev 1:5, 11; 3:2; 7:14; 17:6). 2 Chr 35:12 tries to reconcile the Passover ritual found in Exodus 12:8–9 and in Deuteronomy 16:7. The “as it is written” formula in Ezra 3:4–5 references Deut 12:5–6 and Num 28–29. Nehemiah 8:14–15; 10:29; 13:1–2 refer to Deuteronomy, especially Deut 23:3–5, and to Lev 23; 25 and Num 28–29. Again, these postexilic passages are simply referring to verses within these biblical books. Neither their arguments, nor their authority reside upon Moses as author.

Hence, the first time that the Old Testament even associates Moses with the writings from Exodus to Deuteronomy appears in the postexilic period—very late within the biblical tradition. The OT evidences a developing tradition regarding Moses and the Pentateuch. Within the Pentateuch itself he composes a few verses; within the Deuteronomistic history he is associated with the book of Deuteronomy; within the postexilic books he is associated with the Pentateuch.

The names of biblical books, which we take for granted, were anachronistic to biblical times, as were chapter and verse numbers. So scrolls were often identified by prominent historical figures. The Pentateuch or Torah was associated with Moses, Proverbs with Solomon, and the Psalms with David (e.g., Hebrews 4:7 uses the shorthand phrase, “in David,” to introduce a quote from Psalm 95, which is not entitled “a psalm of David” in the Hebrew OT). Even the biblical scrolls/books that we currently identify by biblical figures (e.g., Joshua, Judges, Ruth, 1–2 Samuel, Esther, and Job) are anonymous, as are 1–2 Kings and 1–2 Chronicles. Evidently, a scrolls/book’s authority and inclusion in the sacred canon were not tied to its supposed authorship.

Mark 1:2–3 illustrates how the NT refers to OT passages. The formula, “As it is written in Isaiah the prophet,” might lead us to expect the citation comes from that biblical book and from that author. Instead, it includes a conflation of phrases drawn from Exod 23:20; Mal 3:1; Isa 40:3. The issue of authorship is beside the point. The Gospel writer likely specifies Isaiah either because the Isa 40:3 citation is the most important or because Isaiah is the book that introduces the Prophets section within the canon of the Law, the Prophets, and the Writings.

Duplications in the Pentateuch

► The Pentateuch contains separate, duplicate accounts of the naming of certain sites and figures.

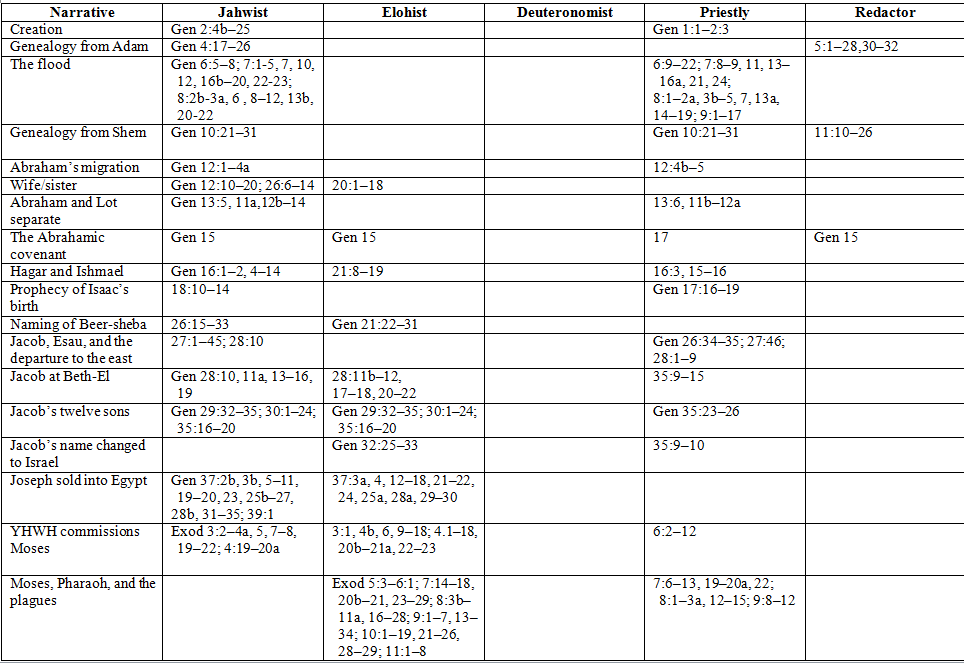

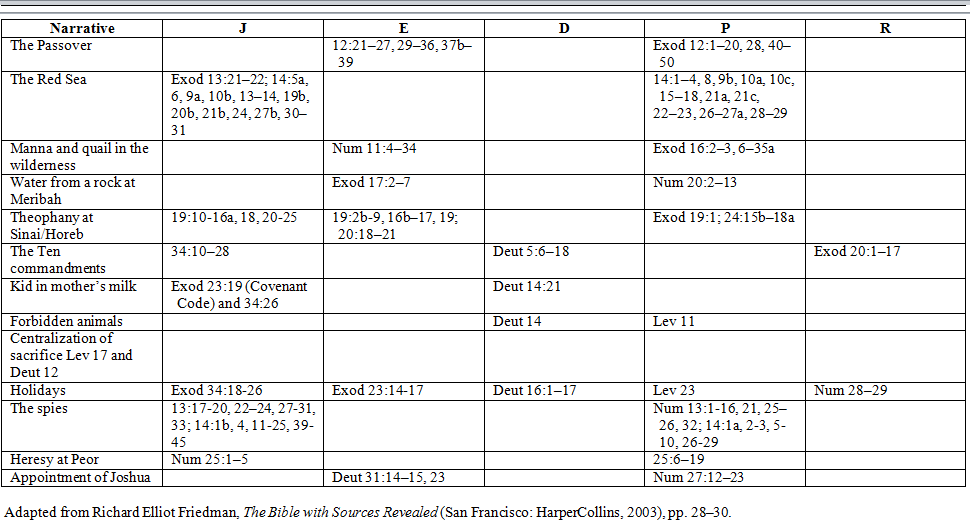

First, we should observe that the Pentateuch contains numerous duplicate accounts. Here is a sampling, arranged according to their theorized sources.

Naming. The Pentateuch contains a number of instances where a site or person is newly named or renamed on two or more separate occasions. None of the later passages refer to or seem aware of the previous occasion. Rather, the second accounts present this as the first time this place or person has received this new name.

Beersheba.

At that time Abimelech, with Phicol the commander of his army, said to Abraham, “God is with you in all that you do; now therefore swear to me here by God that you will not deal falsely with me or with my offspring or with my posterity, but as I have dealt loyally with you, you will deal with me and with the land where you have resided as an alien.” And Abraham said, “I swear it.” When Abraham complained to Abimelech about a well of water that Abimelech’s servants had seized, Abimelech said, “I do not know who has done this; you did not tell me, and I have not heard of it until today.” So Abraham took sheep and oxen and gave them to Abimelech, and the two men made a covenant. Abraham set apart seven ewe lambs of the flock. And Abimelech said to Abraham, “What is the meaning of these seven ewe lambs that you have set apart?” He said, “These seven ewe lambs you shall accept from my hand, in order that you may be a witness for me that I dug this well.” Therefore that place was called Beer-sheba; because there both of them swore an oath. When they had made a covenant at Beer-sheba, Abimelech, with Phicol the commander of his army, left and returned to the land of the Philistines (Gen 21:22–32, NRSV).

26 Then Abimelech went to him from Gerar, with Ahuzzath his adviser and Phicol the commander of his army. 27 Isaac said to them, “Why have you come to me, seeing that you hate me and have sent me away from you?” 28 They said, “We see plainly that the Lord has been with you; so we say, let there be an oath between you and us, and let us make a covenant with you 29 so that you will do us no harm, just as we have not touched you and have done to you nothing but good and have sent you away in peace. You are now the blessed of the Lord.” 30 So he made them a feast, and they ate and drank. 31 In the morning they rose early and exchanged oaths; and Isaac set them on their way, and they departed from him in peace. 32 That same day Isaac’s servants came and told him about the well that they had dug, and said to him, “We have found water!” 33 He called it Shibah; therefore the name of the city is Beer-sheba to this day (Gen 26:26–33, NRSV).

The city of Beersheba is named twice in the ancestral narratives, with neither narrative referring to the other. In both accounts the biblical ancestor has a dispute with Abimelech, whose commander is Phicol. He explicitly acknowledges that God is with the biblical ancestor. In each case there is an issue over a well dug by the ancestor. (Both passages share a rare prepositional phrase in Hebrew: “about the well” [‘al-’odowth be’er].) A water source is obviously an essential, though often disputed, commodity in such an arid region. Conflict, either real or potential, is resolved by means of a covenant and oath, in order to ensure that they show mutual loyalty and refrain from harm. Beersheba is named by a Hebrew word play. “Beer-” means “well” and “-sheba” is related to the covenant ceremony. In the Abraham story it is related to the “seven” (sheva‘) ewe lambs, but in the Isaac story to “Shibah” or “oath” (shevu‘ah). These parallel narratives raise the obvious question, if Beersheba is named in Abraham’s generation, why does it need to be named again in Isaac’s? Apparently, the Abraham of Genesis 21 did not inform the Isaac of Genesis 26.

Bethel. The book of Genesis contains double namings for both the site of Bethel and the ancestor Jacob. In one strand these occur in two discrete passages (Gen 28:10–22; Gen 32:22–32); in another they are combined in a single, much briefer passage (Gen 35:9–15).

10 Jacob left Beer-sheba and went toward Haran. 11 He came to a certain place and stayed there for the night, because the sun had set. Taking one of the stones of the place, he put it under his head and lay down in that place. 12 And he dreamed that there was a ladder [or rather “staircase”] set up on the earth, the top of it reaching to heaven; and the angels of God were ascending and descending on it. 13 And the Lord stood beside him [or rather “above it,” i.e., the staircase] and said, “I am the Lord, the God of Abraham your father and the God of Isaac; the land on which you lie I will give to you and to your offspring; 14 and your offspring shall be like the dust of the earth, and you shall spread abroad to the west and to the east and to the north and to the south; and all the families of the earth shall be blessed in you and in your offspring. 15 Know that I am with you and will keep you wherever you go, and will bring you back to this land; for I will not leave you until I have done what I have promised you.” 16 Then Jacob woke from his sleep and said, “Surely the Lord is in this place—and I did not know it!” 17 And he was afraid, and said, “How awesome is this place! This is none other than the house of God [beth ’elohim], and this is the gate of heaven.” 18 So Jacob rose early in the morning, and he took the stone that he had put under his head and set it up for a pillar and poured oil on the top of it. 19 He called that place Bethel; but the name of the city was Luz at the first. 20 Then Jacob made a vow, saying, “If God will be with me, and will keep me in this way that I go, and will give me bread to eat and clothing to wear, 21 so that I come again to my father’s house in peace, then the Lord shall be my God, 22 and this stone, which I have set up for a pillar, shall be God’s house; and of all that you give me I will surely give one-tenth to you.” (Gen 28:10–22, NRSV)

6 Jacob came to Luz (that is, Bethel), which is in the land of Canaan, he and all the people who were with him…. 9 God appeared to Jacob again when he came from Paddan-aram, and he blessed him. 13 Then God went up from him at the place where he had spoken with him. 14 Jacob set up a pillar in the place where he had spoken with him, a pillar of stone; and he poured out a drink offering on it, and poured oil on it. 15 So Jacob called the place where God had spoken with him Bethel. (Gen 35:6, 9, 13–15, NRSV)

In both of these parallel accounts Jacob changes the name of the Canaanite city of “Luz” to “Bethel,” which means “house of God/El.” To commemorate God’s appearance (theophany) he sets up a pillar (lit. “standing stone”) and pours oil upon it. During the appearance God promises the land to Jacob and his offspring (for the second account, see below).

Israel.

22 The same night he got up and took his two wives, his two maids, and his eleven children, and crossed the ford of the Jabbok. 23 He took them and sent them across the stream, and likewise everything that he had. 24 Jacob was left alone; and a man wrestled with him until daybreak. 25 When the man saw that he did not prevail against Jacob, he struck him on the hip socket; and Jacob’s hip was put out of joint as he wrestled with him. 26 Then he said, “Let me go, for the day is breaking.” But Jacob said, “I will not let you go, unless you bless me.” 27 So he said to him, “What is your name?” And he said, “Jacob.” 28 Then the man said, “You shall no longer be called Jacob, but Israel, for you have striven with God and with humans, and have prevailed.” 29 Then Jacob asked him, “Please tell me your name.” But he said, “Why is it that you ask my name?” And there he blessed him. 30 So Jacob called the place Peniel, saying, “For I have seen God face to face, and yet my life is preserved.” 31 The sun rose upon him as he passed Penuel, limping because of his hip. 32 Therefore to this day the Israelites do not eat the thigh muscle that is on the hip socket, because he struck Jacob on the hip socket at the thigh muscle. (Gen 32:22–32, NRSV)

9 God appeared to Jacob again when he came from Paddan-aram, and he blessed him. 10 God said to him, “Your name is Jacob; no longer shall you be called Jacob, but Israel shall be your name.” So he was called Israel. 11 God said to him, “I am God Almighty: be fruitful and multiply; a nation and a company of nations shall come from you, and kings shall spring from you. 12 The land that I gave to Abraham and Isaac I will give to you, and I will give the land to your offspring after you.” (Gen 35:9–12, NRSV)

In both of these parallel accounts God blesses Jacob and changes his name to Israel. But in the first account this event takes place at Peniel/Penuel east of the Jordan River (along the Jabbok River, west of Mahanaim [Gen 32:2] and east of Succoth [Gen 33:17]), and in the second combined account it takes place at a different location, Bethel. The second combined account is much briefer. It lacks any etymological explanation for the new names. The first accounts explain Bethel (beth-’el) as “the house of God” (beth ’elohim) and Israel (yiśrāʾēl) in connection with “for you have striven [śārîtā] with God and with humans, and have prevailed.” They are also much more graphic in their physical descriptions of divine figures. In the dream account Yahweh is described as “standing” (Gen 28:13), and in the wrestling account the figure who blesses and names him is described as a “man” (Gen 32:24).

Yahweh.

And to Seth also was born a son, and he called his name Enosh. Then it was begun to call on the name of Yahweh (Gen 4:26).

And Moses said to God, “If I come to the Israelites and I say to them, ‘the God of your fathers has sent me to you,’ and they will say to me, ‘What is his name?’ What shall I say to them?” God said to Moses, “I am who I am.” And he said, “thus you shall say to the Israelites, ‘”I am” has sent me to you.’” And God also said to Moses, “thus you shall say to the Israelites, ‘Yahweh, the God of your fathers, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, has sent me to you. This is my name forever, and this is my Memorial-name to all generations’” (Exod 3:13–15).

God spoke to Moses and said to him, “I am Yahweh. I appeared to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob, as God Almighty, but by my name Yahweh I did not make myself known to them (Exod 6:2–3, “I am Yahweh” is repeated three times in Exod 6:6–8).

According to the first account, the name Yahweh is first invoked in primeval times, long before Abraham and Moses. Nevertheless, in the second, Moses at the burning bush explicitly confesses that neither he nor the Israelites know God’s name, Yahweh. Moses requests this insider information as a means of verifying that he has indeed had a private audience with their God. The third account is a divine speech, beginning and ending with the declaration “I am Yahweh.” He presents this as a pivotal moment, up to which God has been invoked by the name “God Almighty,” but now is to be known by the name “Yahweh.”

“You shall not boil a kid in its mother’s milk.” This strange ritual prohibition is repeated three times in the Pentateuch. In each case it is appended to a liturgical calendar (see immediately below, Exod 23:19; 34:26) or to a list of clean and unclean foods (Deut 14:21).

Liturgical Calendars. Liturgical calendars are important to many religions. For Christians, the four Sundays of Advent prepare them for Christmas, and the season of Lent prepares them for Good Friday and Easter. Similarly, the OT has the three pilgrimage festivals of Passover, Weeks/Pentecost, and Tabernacles/Booths. The Pentateuch contains no less than five liturgical calendars: Exod 23:14-17; 34:18-23; Lev 23:1–44; Num 28:1-29:40; Deut 16:1–17. The first two calendars name the festivals by their agricultural designation: Unleavened Bread, Harvest, and Ingathering. The remaining three list them by their more familiar historical designations: Passover, Weeks, and Tabernacles. They also contain considerably more details, and the calendars in Leviticus and Numbers include additional observances.

Duplications in the book of Exodus. The book of Exodus contains numerous duplicate passages, some of which are discussed in some detail in Module 8. These include the dialogue at the burning bush (esp. Exod 3:7–10), the rites of Passover (Exod 11–13), the crossing of the Reed Sea (Exod 14), and Moses’ ascents up Mount Sinai after the giving of the law (Exod 24). In addition, there are two law codes (Exod 20:1–23:33; 34:10–27) and three covenants (Exod 24:7–8; 31:16; 34:10, 27).

Duplications in the Ancestral Narratives (Gen 12–50). (See Module 9.)

Duplications in the Creation Accounts (Gen 1–3). (See Module 10.)

The Duplications Align among Coherent Literary Strands

► These duplications appear to reflect 4-5 literary strands or sources (JEDP).

The duplications that we have observed above can be traced along coherent threads. In other words, they are not just isolated pearls; the pearls align along four to five distinct strands that cover the entire range of the Pentateuch. These strands share common vocabulary and common perspectives and themes.

The prevailing theory for reconstructing the Pentateuchal strands is called the “Documentary Hypothesis,” also known as JEDP, which is an acronym for the postulated sources.

J = Jahwist/Yahwist (Jahwist represents the German spelling). This source takes its name from the divine name, Yahweh, which is used from the beginning of this strand (Gen 2:4; cf. 4:26). It provides the overall plot line of the Pentateuch and contributes most of the narratives. Its portrayal of Yahweh tends to be anthropomorphic.

E = Elohist. This source is name from the divine name, Elohim, which is the Hebrew word most frequently used for “God” in the OT. Its portrayal of Yahweh is slightly more remote. For example, he sometimes appears in dreams, rather than in direct conversation (as in J). This strand features the Sinai covenant and law code.

D = Deuteronomist. This source is essentially the book of Deuteronomy, at least its earliest sections (see further Module 12). Deuteronomistic verses have likely also been inserted elsewhere in the Pentateuch, especially in Exodus. Its theological perspective and themes can be summarized as one God, one sanctuary, and one covenant. The word/Torah of God takes center stage over theophanic revelations (as in the appearance of the God of the skies at Sinai). Moses is a central figure and mediator, along with the Levites/Levitical priests.

P = Priestly. Most of this strand centers on Yahweh’s revelations to Moses at Mount Sinai (Exod 25–31; 35–40; Lev 1–16, 27). The content focuses on sacred personnel in the priests, sacred space in the tabernacle, and sacred rituals, such as sacrifice and festivals.

H = Holiness Code. This strand is found primarily in Leviticus (Lev 17–26). Whereas in P the priests are “holy,” in H all the people are to be “holy” (esp. Lev 19:2; 20:7, 26). While P privileges sacred space (“holy place”), H privileges sacred time, especially Sabbath.

The Literary Strands Reflect the Historical Development of Israelite Religion

► J and E allow for multiple altars, while D later permits only one. D refers to "levitical priests," while P later distinguishes priests from Levites.

Not only do the duplicate passages of the Pentateuch cohere into four or five literary strands, these literary strands align with historical developments in Israel’s religion, as recorded in the Bible itself. The customs and laws contained in JE reflect those found in 1–2 Samuel. For example, Exodus 20:22–26 (E) allows for multiple altars. So Samuel built an altar at his hometown of Ramah (1 Sam 7:17), and David builds an altar to forestall a plague (2 Sam 24:18, 21, 25). But the book of Deuteronomy (D) permits only one altar and one sanctuary (Deut 12:5–6), which is a code followed by the narrator in 1–2 Kings and especially by King Hezekiah (2 Kgs 18:4, 22) and most notably by King Josiah (2 Kgs 23:4–20). The pre-exilic prophetic book of Jeremiah also echoes this Deuteronomic principle of a single sanctuary.

Deuteronomy refers to “Levitical priests,” as does 1–2 Kings. But the Priestly strand of the Pentateuch (P) clearly distinguishes “Levites,” who are descendants of Levi (one of the 12 sons of Jacob), and “priests,” who are descendants of Aaron (a later descendent of Levi). Levites are clearly subordinate to priests. 1–2 Chronicles echoes this distinction and subordination, unlike the parallel texts in Samuel–Kings. The question emerges, if this distinction were in place in the time of Moses, then why does it not surface in Deuteronomy, which purports to be a series of Mosaic sermons, or in Samuel–Kings?

► During the exilic period Ezekiel presents the priest-Levite distinction as a new policy. The Chronicler adopts this new distinction when he retells the Deuteronomistic History.

The exilic prophetic book of Ezekiel may contain a clue. In the book’s final section, a vision of the new temple (Ezek 40–48), the prophet announces judgment on the Levites, “who went far from me when Israel went astray, who went astray from me after their idols” (Ezek 44:10). Their punishment is, “they shall not come near to me to serve me as priest, nor to come near to any of my holy objects, nor to my most holy things” (Ezek 44:13). Instead, they shall have “oversight at the gates of the house” and “slaughter the burnt offering and sacrifice for the people, and they shall stand for them to minister to them” (Ezek 44:11). By contrast, “Levitical priests, the sons of Zadok, who kept charge of my sanctuary when the Israelites went astray from me, they shall come near to me to minister to me. And they shall stand before me to offer me the fat and the blood—an utterance of the Lord Yahweh. They shall enter my sanctuary and they shall come near to my table to minister to me” (Ezek 44:15–16). Ezekiel is in agreement with the Priestly strand of the Pentateuch, but he introduces the subordination of the Levites to the priests as a new policy! This development may explain why the Deuteronomistic history makes no distinction between priests and Levites, but the Chronicler’s history does.

In view of these considerations, most scholars locate the four main strands or sources to the following time periods and locations.

Jahwist source is the earliest, reflecting the perspective of Judah that Jerusalem is the rightful capital of the United Monarchy, dating to the 10th/9th century B.C.E.

Elohist source reflects the perspective of northern Israel (Ephraim), dating to the 9th/8th century BCE.

JE sources were combined after the northern kingdom falls to the Assyrians in 722 BCE, in part to unite the refugees from the northern kingdom with the kingdom of Judah.

Deuteronomist source likely originated among the Levites of northern Israel and shares many common themes with the prophetic book of Hosea. After 722 BCE, they likely fled south to Judah as refugees. The archaeology of Jerusalem, in fact, reflects population growth at the end of the eighth century when Hezekiah was king. Their influence likely prompted the religious reform of Hezekiah and possibly his attempted rebellion against the Assyrian Empire. His successor, Manasseh, instead complied with Assyrian rule and thus probably suppressed Deuteronomy and its policies. This sequence would explain its later discovery during Josiah’s reign.

Priestly source, while certainly containing older traditions, was probably compiled during the sixth century exile in Babylon.

The Benefits of Analysis and Synthesis

► Whether or not one finds the JEDP hypothesis convincing, this debate has brought to light the variety of perspectives within the Pentateuch (as in a "mosaic").

JEDP is a “hypothesis” or more accurately a theory because it has considerable explanatory power for the literary, historical, and theological dimensions of the Pentateuch. It can explain what might regarded as contradictions and loose ends, if one were to insist on a single author maintaining a consistent perspective throughout. Nevertheless, it remains a theory and continues to be hotly debated. Readers may choose to reject it, but the observations above, especially regarding duplications, bring to light features of the Pentateuch that demand some kind of alternative proposal.

Some readers might insist on a “final form” or canonical reading of the Pentateuch. Indeed, this is how it has been transmitted as Scripture—not as discrete sources. But, in view of the above, even a final form reading must read the Pentateuch as an edited text, not an authored text written from a single coherent perspective. We shall see that the Bible from the outset in Genesis 1–3 notifies readers that it is presenting revelation through multiple perspectives. Rather than hearing Scripture in “Mono mode,” we hear more when we hear the alternative voices speaking in stereo.

We should recognize that the JEDP writers were not themselves authors who are in command of their material in order to create a coherent narrative. They are editors, gathering together their own disparate sources while connecting them with their own editorial transitions and imbuing them with their own literary themes. They are not the starting point for literary production in ancient Israel, but simply key players in transmitting oral and written traditions into the final form of the Pentateuch.

The Documentary Hypothesis is not merely about literary analysis and attempting to fragment a narrative. Nor is it about historical analysis and attempting to delineate the history of composition or to deconstruct a literal history. Nor is it about religious analysis and attempting to pit one school against another. It is fundamentally about our reading strategy and theological interpretation: how has revelation been packaged in the Pentateuch? What is Yahweh’s means of torah/instruction for his people?

A variety of metaphors might help us to appreciate the value of this kind of analysis and synthesis. The Psalms liken Scripture to light:

A lamp to my feet is your word,

and a light to my path (Ps 119:105).

We usually perceive light as white, but if we see it through a prism, we discover the apparently white light actually consists of the spectrum of the rainbow. JEDP can serve as a prism to the Pentateuch, bringing to light its variety of colors and shades. Israel Knohl’s book on the Pentateuch, The Divine Symphony: The Bible’s Many Voices, suggests another metaphor of a symphony of instruments and a choir of voices. The Pentateuch contains, not just a single melodic line, but a harmony of many lines. Using a metaphor from Judaism and Christianity, the Pentateuch does not represent a single theological perspective or denomination, but perspectives from a variety of denominations. One can also compare the Pentateuch to an archaeological tell. While the tell is singular, it consists of a variety of strata or layers, each with its own fascinating history. To use another metaphor, the Pentateuch is a tapestry or quilt or, perhaps most fittingly, a “mosaic.”

The observations above encourage readers to perceive a variety of colors, textures, and patterns within the fabric of Torah, and to hear a variety of tones and melodies in its music. Theologically, we should understand that the one God cannot be understood from a singular human perspective, but only through many. We gain a deeper appreciation of the panorama of Scripture if we discern the variety of human snapshots that it stitches together.

So, to insist upon the singularity of literary meaning and theological doctrine would be contrary to the very packaging of revelation in the Pentateuch. It would be fallacious to infer that this reading strategy calls into question its inspiration from the one God. Rather, it helps us see that the means by which inspiration is communicated and is meant to be read is through multiple perspectives, which may or may not be completely reconcilable.

The Theme of the Pentateuch

► A/The theme of the Pentateuch is the partial fulfillment of the ancestral promises of posterity, blessing, and land.

Although the Pentateuch is likely the result of a combination of separate sources, it does maintain a measure of coherence, probably attributable to a respectful editor or editors. The J source likely laid the foundation for its theme and motives, as the other sources echo the same theme and motifs, while contributing their own distinctive viewpoints.

David Clines in his book, The Theme of the Pentateuch, offers two definitions of “theme.” The first defines it as an abstract concept made concrete thru plot (which is a narrative of events). The second defines it as the rationale of content, structure, and development (i.e., why this material is there and why it is presented in this order and shape). He posits that “the theme of the Pentateuch is the partial fulfillment—which implies also the partial non-fulfillment—of the promise to or blessing of the patriarchs.” The patriarchal promise (e.g., Gen 12:1-3; 17:1-8) has three elements, each of which is given its place of emphasis: posterity in Gen 12–50, relationship with God in Exodus and Leviticus, and land in Numbers and Deuteronomy.

The posterity element of the promise is given most attention in Genesis. Several crises threaten its fulfillment. At the beginning of the story Abraham and Sarah are childless, and Sarah is beyond the age of bearing children (12:4; 17:17-18; 18:11-12). After 25 years Sarah finally gives birth to Isaac (21:1-7), but some 15 years later God commands Abraham to sacrifice him (22:1-19). God spares Isaac, who later marries Rebekah, but she, like Sarah, is barren for a time (25:21). They eventually give birth to Esau and Jacob (25:21-26), but brotherly rivalries soon threaten Jacob’s life (27:41; 32:6-8; 34:30). Jacob marries Rachel, who is also barren for a time (29:31; 30:1). But they, with the help of Leah, another wife, and two maidservants, give birth to 12 sons (29:31-30:24; 35:18). Though out of brotherly rivalry 11 of these sons scheme to do away with Joseph (37:20; 39:19-20), this plot eventually ensures the rescue of the entire family, which is established in Egypt (46:27).

Centuries later Israel is multiplying in Egypt (Exod 1:7-12, 20), but Pharaoh intends to exterminate all the male infants (1:22). Eventually Yahweh delivers his people out of Egypt, but murmurings and judgments of death en route (14:11-12; 16:3; 17:3) and especially the rebellion with the golden calf (32:9-10, 13) threaten the existence of the people. Even after the people are spared from what they deserve, they are warned that persistent disregard of Yahweh’s commands would bring annihilation, unless they repent (Lev 26:38, 42, 44). Yahweh gives no unconditional guarantees. By the end of the Pentateuch, the promise of posterity made to Abraham is considered fulfilled and a prayer is added that an even greater fulfillment will be realized (Deut 1:10-11).

The nature of the relationship with God promised to the fathers is not spelled out in Genesis. There are the promises of blessing and protection (12:3; 26:3), and a covenant bond (15:1-19; 17:1-27), but exactly what these mean is not stated. In Exodus God “remembers” this covenant with the fathers (Exod 2:24) and so moves to war against Egypt and their gods and to deliver his people from bondage (3:6; 10ff; 6:3, 6-7). He leads his people (13:21-22), and at the Reed Sea he fights as a divine warrior on their behalf (14:13-14, 25; 15:2ff). At Sinai Yahweh reveals himself in fire (19:16-19; 24:15-18) and binds himself to his peculiar people (19:4-6) in a covenant document with its promises and laws on how to maintain this relationship with this holy God (20:1-24:11; Lev, esp. 26:3, 12-13). He also reveals the plan of the tabernacle, his dwelling among them (Exod 25-31; 35-40). But murmuring en route (16:8, 12; 17:7ff) and the golden calf rebellion (chaps 32-34; esp. 32:4, 10, 13, 34; 33:3, 15) jeopardize that relationship. In sum, Exodus presents two events that establish the relationship with God, the exodus from Egypt and the covenant at Sinai, and two challenges to that relationship, the murmurings and the golden calf rebellion. Finally in Deuteronomy the people are reminded of the covenant bond (esp. 26:18-19) and its commandments of love. The relationship cannot be regarded as automatic: Israel must still choose between obedience and disobedience (11:26-28). Even at point of near fulfillment, there is possibility of complete loss.

The promise of land seems the most remote in the Pentateuch. Abraham, upon arriving in the promised land, simply walks straight through it (Gen 12:1-10). The Canaanite possesses in the land (12:6). All he comes to own is a burial plot (23:16-20) and an altar (33:19-20). At crucial points throughout the Pentateuch, the promise of land is repeated (Exod 3:17; 6:4, 8; 13:5, 11; 15:13, 17; 16:35; 23:23, 31; 32:13; 33:1, 3). The land is the assumed stage where Yahweh’s distinctive laws will be lived out (Lev 18:3-4). Throughout their stay in the wilderness the people are reminded that their camp is a moving camp, not a settlement (Num 2:17; 4:5). The fire and cloud before them lead them on their journey (9:17-23). Yet they must fight for this land Yahweh is giving them (e.g., Num 1:3). Murmurings en route (Num 11-21), especially about the inhabitants of Canaan and their defenses (13:31-14:4), raise the question of whether or not they will ever set foot in the promised land. But just east of Canaan they defeat two strong kings, Sihon and Og (21:21-35), which gives them a foretaste of the victory they can achieve under Yahweh. At the very opening of Deuteronomy Moses reiterates that Yahweh is about to give them the land sworn to their forefathers and that they must take it (1:8). The significance of the many laws in Deuteronomy is that fulfillment of them is prerequisite to their possessing the promised land (4:1, 40; cf. 5:31; 6:1; 12:1). The people are reminded no less than 56 times of “the land you are about to possess” and “the land Yahweh your God is giving you”.