Genesis 1-11

10.1. Canonical and Historical Context: Who’s on stage?

► Genesis 1--11 is told retrospectively from a Yahwistic perspective and sets the stage for the Abraham story.

The book of Genesis is true to its name, meaning “origins,” and true to its opening phrase, “In the beginning,” which is how the book is named in the Jewish canon, “Bereshith.” Within the Old Testament and the Pentateuch in particular, it is principally about the origins and beginning of God’s people Israel. Although the scope of the primeval narratives in Genesis 1–11 includes the peoples and nations scattered on the face of the earth, they set the stage for the spotlight to fall on Abraham’s family. The Ancestral Narratives (Gen 12–50) then set the stage for the story of Israel’s defining moments in the exodus out from Egypt and their special covenant with God at Mount Sinai. The lengthy story of Joseph in Genesis 37–50 is largely to explain how the Ancestors, promised the land of Canaan, end up settling in Egypt. Once this is clarified in Genesis 50, there remains a gap of centuries before Exodus 1—about which nothing is said. So Genesis is not meant to narrate an unbroken chain of tradition from Abraham to Moses; it is meant to set the stage for the remarkable liberation and formation of the people of God. In other words, the first “chapter,” so to speak, of the Bible is the book of Exodus. The book of Genesis functions as its prologue.

The book of Genesis is written from a Mosaic perspective, not from that of Noah or Abraham. While the divine name “Yahweh” is first disclosed to Moses (Exod 3: 13–15, E; Exod 6:2–8, P), the J narrator (Yahwist) uses this divine name throughout the book of Genesis to indicate that the God of Abraham is the same deity known to the Israelites as Yahweh. In other words, the book of Genesis is written retrospectively.

10.2. The Primeval Narratives (Gen 1–11)

► In order to read the Primeval Narratives respectfully and according to their inherent "ground rules," we should read them literarily before presuming to read them literally.

No chapters of the Bible are better known, yet also more controversial, than the creation stories of the book of Genesis. Their familiarity has actually fueled the controversy, because most readers assume they know what the stories are about and what claims are appropriate to them. But, out of respect for this ancient literature, we must step back and attempt to hear it on its own terms—for the first time, so to speak. We cannot read it literally until we have first read it literarily. A literal reading assumes that it is some kind of historical, scientific account. That may be our conclusion after we have done our best to ascertain its literary genre, but the genre question must inform our reading strategy.

While people’s ideological and theological positions—whether secularist, liberal, or conservative—are no doubt very important to them, these considerations should not distract us from our responsibility as respectful readers. Our ideological and theological conclusions must come after a reading of these ancient texts that is subject to the “ground rules” and literary conventions appropriate to the ancient writers and their audiences. Our reading strategy should be “conservative” in so far as we attempt to conserve the meaning of these texts as understood within their original social and cultural contexts. The cooperative reader, in order to hear the text properly, will adopt the interpretive strategy of the implied reader, that is, the reader for whom the author(s) wrote the text in the first place. While all readers may not personally hold to the beliefs of the implied reader, they should postpone those judgments until after they have “read” the text with due consideration. The challenge facing modern readers is this: to hear the Bible properly we must be willing to recalibrate our expectations of this literature based upon its own literary conventions.

Each person has cried foul when their text has been interpreted out of context. We must concede the same respect to the biblical writer(s) and so begin by examining the opening chapters of Genesis within their wider literary (i.e., the book of Genesis) and cultural contexts (i.e., Israelite and ANE cultures).

► The thematic functions of the creation stories are to introduce the God of Abraham as the creator of all and to state the problem of human sin.

Literary Context. We will begin with the literary context of the older of the two creation accounts, the Garden of Eden narrative in Genesis 2–3. Prior to the stories about Abraham, Israel’s patriarch, the Primeval Narratives contain a series of “fall” stories: the Garden of Eden (Gen 2–3), Cain and Abel (Gen 4), the sons of God (Gen 6:1–4), Noah’s flood (Gen 6:5–9:27), and the Tower of Babel (Gen 11). (As noted above, each of these episodes is part of the J strand.) They function principally to set the stage for the significance of what God is going to do with Abraham and his family. To grasp the significance and impact of Genesis 1–11 it might be best to ask, how would we read the Abraham narrative differently without these introductory chapters? First, we might assume “the God of Abraham” is simply that, namely a clan deity. But the Primeval Narratives introduce this deity as none other than the maker of the earth and of all humanity. They serve a theological function.

Second, without the Primeval Narratives the significance of the Abraham story would be lost. Why should we care about a distant seminomadic chieftain living in the second millennium BCE? Without a statement of the problem, the importance of the solution is lost. The five narratives preceding Abraham state the problems of human evil and violence (Cain in Gen 4:8–10, the generation of the Flood in Gen 6:5; cf. 6:11–13) and particularly of boundary violations, where humans encroach on the divine to obtain prerogatives belonging to deity (Eden, sons of God, and Tower of Babel). In Eden the man and the woman by eating of “the tree of the knowledge of good and evil” Gen (Gen 2:9, 17) would become like God “knowing good and evil” (Gen 3:5, 22). The most graphic and strangest boundary violation is when “the sons of God” have intercourse with “the daughters of man” (Gen 6:1–4). In fact, the first mention that human nature, to the very “form of their thinking,” became “evil” and “corrupted” (Gen 6:5, 11–13) appears not after the so-called Fall episode in the Eden narrative but after this story about the sons of God, which serves as a prelude to the Flood narrative. Later, “the children of man” attempt to build a tower with its head “in the heavens,” the realm of deity. Yahweh describes this achievement as “the beginning of what they can do, and now not a thing they plan to do will be inaccessible to them” (Gen 11:4–6).

The point of these boundary violations is best illustrated in the transition from the Tower of Babel story (Gen 11) to the Abraham story (Gen 12). In the former, humans seek to make a “name” for themselves (Gen 11:4), but in the latter Yahweh promises to make Abram’s “name” great (Gen 12:2). Grasping for a name is contrasted with receiving a great name from God. Similarly while humans are intent on maintaining their own place in the “land” (Gen 11:2, 4), Abram must be willing to go from his own “land” to the “land” that Yahweh will show him (Gen 12:1). Clearly, declarations of independence from God are considered the root of the human dilemma (according to the J strand).

In sum, the main points of the Primeval Narratives in Genesis 1–11 are (a) to affirm that the God of Abraham is indeed the one God who created the cosmos and humanity and (b) to state the problem of humanity’s propensity to declare itself independent from God.

► Genesis reflects a high concentration of Mesopotamian parallels, which indicates the biblical writers used a common language to convey a radically new theology.

Cultural Context. While not indispensable to understanding the Primeval Narratives, their cultural context sheds considerable light on their meaning and significance. A feature that distinguishes the Primeval Narratives (Gen 1–11) from the Ancestral Narratives (Gen 12–50) is their strong parallels to Mesopotamian myths and epics. After Genesis 11, the parallels stop.

Genesis ANE

7-Day Creation (Gen 1) Enuma Elish

Eden (Gen 2–3) Atrahasis, Adapa, Enki and Ninhursag

Flood (Gen 6–9) Atrahasis, Gilgamesh

Babel (Gen 11) Ziggurats

Their interplay suggests that the biblical writers, writing within their Semitic culture, employed common symbols and storylines to narrate their distinctive understanding of God’s interactions with humans. Although some scholars of the 19th and 20th centuries may have regarded this dependence as an act of plagiarism, it would seem that the biblical writers would have assumed their readers’ prior knowledge of these common Semitic traditions in order to make the punchline of their narratives all the more effective. So, in order to grasp the significance of the Genesis primeval narratives, it would be best first to hear the common Semitic stories of beginnings and then to hear—for the first time—the novel twist of the Hebrew narrative.

10.3. Garden of Eden (Gen 2–3)

The Eden narrative shares themes and motifs with other Semitic cultures: the special creation of humans as a combination of elements from the earth and the divine, why humans are denied eternal life, and the staging of two trees, four streams, and cherub figures.

Info Box 10.1: Atrahasis (Part 1)

Dating from the early 2nd millennium BCE this Babylonian epic includes the creation of humans and the flood, in which Atrahasis is the Noah figure. It begins with the (lower) Igigi gods digging out canals and the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. Their work is described as “forced labor” and “drudgery.” After they threaten rebellion against Enlil, the (higher) Anunna gods decree the creation of humans—with a mixture of clay from the earth and the flesh and blood of a god—to “bear the yoke” and “assume the drudgery of god.”

Info Box 10.2: Adapa

Adapa was priest and servant of the god Ea, who endowed him with such wisdom that “his perception of what pertains to the Anunna-gods was vast.” While he was fishing on behalf of the temple of Ea, the South Wind blew and capsized his boat. In anger Adapa cursed the South Wind and broke its wing. The god Anu then summoned him to heaven. Before going, Ea commanded him to refuse from Anu what he called “food of death” and “waters of death.” After Adapa explained his actions, Anu asked, “Why did Ea disclose what pertains to heaven and earth to an uncouth mortal? … Since he has so treated him, what, for our part, shall we do for him? Bring him food of life, let him eat.” But the narrator informs us that after Adapa refused “food of life” and “waters of life,” “Anu stared and burst out laughing at him, ‘Come now, Adapa, why did you not eat or drink? Won’t you live? Are not people to be im[mor]tal?’ Ea my lord told me, ‘You must not eat, you must not drink.’ ‘Let them take him and [ret]urn him to his earth’” (COS 1.129). In this rivalry between the gods Anu and Ea, the human Adapa, to whom was disclosed the ways of heaven and earth, thus loses his chance to obtain eternal life because he chose to obey the command of Ea and refused Anu’s offer.

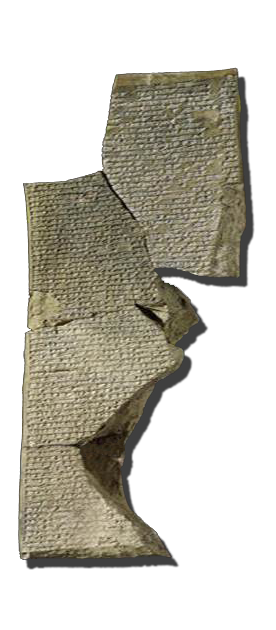

Info Box 10.3: Mesopotamian Imagery and Terminology

In this 13th century BCE ivory inlay from Asshur in northern Mesopotamia, four streams issue from a deity, flanked by two trees that are protected by two winged bulls.

Some of the terms used in the Genesis Narratives are difficult to translate without consulting Mesopotamian literature. The Hebrew word translated “stream” or “mist,” which “goes up from the land and waters all the face of the ground” (Gen 2:6) is best explained as a loanword from Mesopotamia, meaning “inundation.”

► As the Eden narrative is packaged as literature, we must understand Yahweh God as a literary character, rather than imposing our own theological system upon him.

Although the Bible is a source for the theologies of Jews and Christians, we must be intent on first respecting how theology is presented to us in Genesis, namely as narrative, which has a setting, a plot, and characters—one of which is God. “The Lord God” (Yahweh God, in Hebrew) must be interpreted as a literary character—before one can infer the narrative’s contribution to one’s theology. To hear the story properly we must restrict our expectations to the confines of the narrative: it sets a scene, characterizes the characters, describes actions, and reports speeches. But if, for example, readers read characteristics into God’s character that are beyond the bounds of the narrator, they are not reading the narrator’s story but one they have constructed themselves by their imported theology. In other words, our theological system can actually be an impediment, distracting us from hearing the Bible.

► Yahweh God is portrayed anthropomorphically (as potter, gardener, physician, craftsman, and tanner), not as the omniscient God of theology.

Who is “Yahweh God”? The literary portrayal of Yahweh God in the Primeval Narratives is considerably different from that of standard Jewish and Christian theology. The gap between the human and the divine is much narrower. Once humans eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, Yahweh God admits, “the man has become like one of us knowing good and evil” (Gen 3:22). In the Tower of Babel story, the physical realm of deity is not far and at least theoretically attainable: “the children of the man” attempt to build a skyscraper, “a tower with its head in the skies/heavens” (Gen 11:4, Hebrew has only the one word, shamayim). The Eden narrative portrays Yahweh God in several anthropomorphic roles: using soil he “forms/shapes” the man and the animals like a potter (Gen 2:7, 19), he “plants” a garden like a gardener (Gen 2:8), he anesthetizes the man and surgically removes his rib like a physician, and from it he “builds” woman like a carpenter (Gen 2:22), and finally he clothes them with skins as a tanner (Gen 3:21). Yahweh God is not omnipresent. After the serpent’s conversation with the woman, Yahweh God suddenly appears on stage making a “sound” when he “strolls” (literally, “walks back and forth”) “in the garden at the breeze of the day” (Gen 3:8). As he has a “face/presence” from which the humans can hide, he appears to be portrayed in some bodily form. Nor is Yahweh God omniscient. He observes a deficiency in his garden and rectifies the problem by trial-and-error. He is curious “to see what” the man “would name” the creatures that he “brings” to him. After appearing in the garden he asks his gardener, “Where are you?” and “Who told you?” (Gen 3:9, 11). To modern readers this may seem incomprehensible but to the ancient Hebrews it was evidently “kosher.” And, as we shall see, this “bodily” incarnation of Yahweh God, so to speak, makes possible and comprehensible the lively interaction between God and the man and the woman.

► Using familiar ANE motifs of humans working the ground, a garden with 2 trees and 4 rivers, and the cherub, the OT presents Yahweh God as a unique deity who attends to the needs of humans.

Genesis 2. The narrative’s opening interest lies in a local garden: there is none because there is no gardener. The stated reason the Lord God creates “the man” (’adam) is “to work/serve the ground” (’adamah) and to “keep/guard it” (Gen 2:5, 15). The garden exists not for the man but for Yahweh (cf. Isa 51:3), where he can enjoy his late afternoon strolls. Yahweh manufactures his laborer/gardener as a potter who “shapes” the “dust/soil” from the “ground” and combines it with his “breath.” Once the man is made, Yahweh himself “plants” a garden in “Eden” (a term that means “delight/bliss”) with “trees that are desirable to the sight and good for eating,” including two special trees. Watering this garden is “an inundation” that divides into four rivers, including the Tigris and Euphrates (which form Mesopotamia, the land between the rivers, Gen 2:6, 10–14). Ancient readers would be familiar with this imagery from the gardens adjoining a deity’s temple or the king’s palace. Later, we learn of “cherubim” (otherworldly, extra-terrestrial, hybrid creatures with wings) that Yahweh stations to guard entry into the garden (Gen 3:24).

Info Box 10.4: Paradise?

Upon closer inspection the Garden of Eden is not the paradise that many readers have come to expect. Humans are made specifically to work the ground and to “guard” the garden. From what? Implicitly the garden and the humans live under some kind of threat. Moreover, Eden was not made for their pleasure, but for God’s.

It was the Septuagint translators who translated the Hebrew word for “garden” as paradeisos, not to mislead readers but because its usage was based on the Persian word for an enclosed garden/park usually adjacent to the royal palace.

Thus far, the motifs of Genesis 1–3 are familiar from ancient Near Eastern culture. Humans were made by combining earth with something divine for the purpose of working the ground in the service of deity. But what follows would make ancient Near Eastern heads turn: this Yahweh God attends to the needs of humans! He provides food and human partnership, and even seeks them out as conversation partners. Remarkably, the supervising deity permits the laboring gardener to eat freely from any tree in the orchard, aside from one—“the tree of the knowledge of good and evil” (the significance of which will be explained below). Then Yahweh notices a deficiency in his garden: “it is not good that the man is alone.” He lacks “a helper corresponding to him.” To rectify the problem he engages in an experiment to “find” (Gen 2:20), that is, to discover such a one. He resumes his role as potter by “shaping” from the “dust/soil” (without mention of divine breath) animals and birds and “brings/escorts” them to the man “to see what he would name them.” The literary character of Yahweh God wants to discover his gardener’s perception of naming and thus recognizing the suitability of “a helper corresponding to him.” The experiment fails.

In the second experiment, Yahweh, as physician, anesthetizes the man and surgically removes a rib, from which as a craftsman he “built” woman, whom he “brought/escorted” to the man. In the narrative’s first poetic speech the man declares this experiment a success—“at last,” implying the process has been lengthy (Gen 2:23).

► The "clever" serpent figure questions Yahweh God's words and raises the issue of entitlement.

Genesis 3. The serpent is introduced as one of “the creatures of the field” (Gen 3:1), whom Yahweh had apparently formed earlier and escorted to the man for naming (Gen 2:19). This creature and the man at least must have met before. Its name “serpent” (nāḥāsh), which in Hebrew resonates with “divination”(naḥash), must be the one the man had given it. We should not imagine the conversation between the serpent and the woman was private because the man “was with her” throughout this scene (Gen 3:6). While the man and the woman are “naked” (‘arom), the serpent is “clever” (‘arum). Most English translations render this Hebrew word as “crafty,” thus inclining readers to view this creature of Yahweh negatively. While in some OT contexts this connotation may be appropriate, this Hebrew word occurs most frequently in the book of Proverbs (8 times), where it is always translated “prudent”! The basic, underlying sense of the Hebrew word is “clever,” which is an attribute that can be used for good or ill. Serpents were viewed ambivalently in both the OT and the ANE. Like snakes, they are hostile to humans with their bite (Gen 3:15). But when Jesus in the NT admonishes his disciples to be “wise as serpents” (Matt 10:16), he refers to their cleverness as admirable. Most remarkably, however, this serpent is so clever that he can speak! Indeed, Yahweh speaks to the serpent. While God’s curse means that the serpent will be without legs, no mention is made that he will be without speech. As with the cherubim figures at the narrative’s close, these symbolic figures of the ANE clearly point to the symbolic nature of the narrative’s genre.

The serpent first questions the woman on what God really said or meant by selectively quoting and transposing “not” from God’s earlier words.

“From any tree of the garden you may indeed eat, but from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you may not eat from it, for in the day you eat from it, you shall indeed die” (Gen 2:16–17).

“Did God really say, ‘You shall not eat from any tree in the garden’” (Gen 3:1).

In his second speech (Gen 3:4–5) he contradicts God’s death sentence (Gen 2:17b) and claims “your eyes will be opened and you will become like God, knowing good and evil”—each of which proves to be true. Instead of dying “in the day” they eat, they are expelled from the garden (Gen 3:23–24). Their eyes are opened, though to knowledge that they are naked, not clever (Gen 3:7). In the end even Yahweh acknowledges, “the man has become like one of us knowing good and evil” (Gen 3:22). The serpent nowhere lies, though he does mislead. He questions and insinuates that God’s motives are self-serving and defensive regarding his exclusive hold on knowledge. In short, he raises the issue of entitlement with the garden’s laborers.

► Yet Yahweh God is a generous CEO who invites his laborers to partake of every tree in the orchard, except for one that he reserves for himself.

The woman correctly perceives the tree as God had made it, that is, “good for eating and a desirable sight” (cf. Gen 3:6 and 2:9). There is nothing wrong with the tree’s fruit per se. Indeed, elsewhere in the OT “gaining insight” (Gen 3:6) is encouraged (Pss 14:2; 119:99; Prov 1:3 and numerous times; Jer 3:15) and “knowing good and evil” is a sign of adult maturity (Deut 1:39; Isa 7:15–16). But within the ground rules laid down in this narrative, this was the sole tree that the divine proprietor had reserved for himself, whose property it is “to know good and evil” (Gen 3:22). (Does this imply that Yahweh eats of this tree?) The man and the woman are guilty of trespassing over a divine boundary. The issue is not simply disobeying God’s command (Gen 2:16; 3:11, 17): it was their sense of entitlement that enticed them to transgress into divine property. The Hebrew narrator may be engaging in wordplay: the serpent (nāḥāsh), in effect, encourages “divination” (naḥash), that is, an illicit means of obtaining divine knowledge. While the goal of obtaining divine knowledge may be a good thing, the offence lies in the means of grasping for what God has not granted. The narrative implies that temptation can be subtle, sneaky, and pernicious—just like a snake. It sets the stage so the characters are able to embody in their speeches the factors that typify temptation.

► God's punishment is exile from the garden, which deprives the Man and the Woman access to "the tree of life," destining them to death.

The actual consequence for this transgression is not death “in the day of their eating,” but expulsion from the Garden of Eden and the appointment of cherubim “to guard the way to the tree of life,” “lest … he take from the tree of life and eat and live forever” (Gen 3:22–24). Without access to “the tree of life,” the “breath of life” that Yahweh had breathed into his nostrils (Gen 2:7) cannot be maintained and so human identity is reduced to dust, as Yahweh himself says, “you are dust” (Gen 3:19). The narrative is explicit that to “live forever” humans must have access to this single tree in the garden. Maintenance of the breath of life is ever contingent on Yahweh. “Living forever” is a special case made possible only by regular access to this tree. In other words, immortality is not a property that the human soul possesses. The implication is that, apart from this access, death is not a new condition but the assumed outcome of all God’s creatures, especially for those outside this localized garden. Yahweh had initially delivered the threat of death to the man without explanation (Gen 2:16–17), likely because it was the assumed fate of every creature.

In contrast to the common storylines familiar from their ANE cultural environment, the Hebrews were taught that humans lose access to the tree of life by their own trespass, not because they happen to be pawns in a rivalry among the gods. They toil, not because they are lackeys to the gods, but because they disobey God.

► Embedded in the narrative is temple symbolism, which gave ancient Israelites hope of reentering Yahweh's garden by accessing the temple.

“Eden” and the Temple. But to the ancient Hebrew readers this was not the end of the story. As noted above, temples had gardens. The description of the structure of Solomon’s temple and its related furniture includes adornments of trees, flowers, and especially cherubim (1 Kgs 6:29, 32, 35; 7:36; further on cherubim see 1 Kgs 6:23–28; 7:29). Prominent in Ezekiel’s vision of a new temple is a life-giving river (Ezek 47:1–12; Joel 3:18; Zech 14:8), on the banks of which are trees whose fruit will be for eating. The Psalms, the temple’s hymn book, also refer to trees in Yahweh’s house (Pss 52:8; 92:12–13) and to a river issuing from the sanctuary (Ps 46:4). Eden imagery is most explicit in a psalm celebrating the benefits of entering the temple: “With the river of your delights you give them drink, for with you is a spring of life” (Ps 36:8–9). The Hebrew word for “delight” is ‘eden. Thus, while the man and the woman were expelled from Eden in the narrative of Genesis 2–3, Yahweh as host of his “house” offers his worshipers access to drink from the “river of Eden” and so gain “life.” In the ears of his worshipers the Eden narrative rings not so much as a story of the remote past as a symbolic reminder that reentry into Eden is possible via the temple.

► The Yahwistic narrator stitches together familiar ANE stories to portray a radically new worldview of God and the human condition.

What type of literature is Genesis 2–3? Now that we have highlighted key themes and cultural echoes of the Eden narrative, we are a better position to come to terms with its literary genre. Several observations should help.

Narrator’s Perspective. While the Eden narrative comes before Moses and even Abraham, the narrator writes from the retrospective viewpoint of the Israelite monarchy. This begs the question, what were his sources?

Discontinuous, Episodic Narratives. While the individual narratives of Genesis 1-11 have been integrated into a thematic whole (establishing Yahweh as creator and the human inclination to encroach on the divine realm and to declare one's independence from God), they are discontinuous from one another. In the subsequent Cain narrative, readers might ask, where did his wife come from? Who is there to inhabit the city he builds? Who would form the posse that he fears? There is no link or transition to the next narrative about the sons of God (Gen 6:1–4), nor then to the Flood narrative (Gen 6–9), nor then to the Tower of Babel and then to Abraham. Even within the Eden narrative itself, some verses read like later insertions (Gen 2:10–14, 24; 3:20–21). The narrator appears to be an editor, who is reworking originally independent and unrelated narratives. Nothing in the narrative sequence suggests a continuous chain of tradition passed from one generation to the next.

ANE Stories. As noted above, the narrator cuts his narrative cloth from familiar ANE stories in order to portray a novel theology of Yahweh and anthropology for Israel.

Info Box 10.5: Adam

Twenty times the Eden narrative simply refers to “the man” (the ’adam or ha’adam). Adam, as a proper name, appears only three times in most English translations (Gen 2:20; 3:17, 21), but in each case it is prefixed with the Hebrew preposition “to/for” (l in Hebrew, thus le’adam). Given the prevailing references to “the man,” the most natural reading of the consonantal Hebrew text is “to/for the man.” (The Hebrew vowel points were not inserted until around the 9th century C.E.) It is likely we should also read “the man” in Gen 4:25. Hence, the first mention of “Adam” as a proper name in the Bible appears in the Priestly genealogy (Gen 5:1).

Type Scenes and Characters. While set in the distant past, the narrative employs character types, which are typical of human behavior and not unique to particular individuals and events. The Man and the Woman (named “Eve, which means “Living One,” as she becomes “the mother of all living” in Gen 3:20) live in the land of Bliss. Though generously supplied by Yahweh God, they feel entitled to what is prohibited and so aspire to become like gods. When cornered with an accusation, the Man passes the buck to the Woman, and the Woman to the Serpent (Gen 3:12–13). This is the story of Everyman and Everywoman.

Etiologies. The Eden narrative serves an etiological function of explaining the causes for present realities: man’s (’adam) tie to the ground (’adamah), weeds and why his work is so toilsome, woman’s pain in childbirth, male dominance, why snakes crawl and are hostile to humans, and death as a return to the dust. This etiological function is especially noticeable in the awkward verse that explains the origins of marriage as leaving father and mother (Gen 2:24). Finally, the expulsion from the Garden powerfully foreshadows the threat of exile that both Israel and Judah will later suffer. Genesis 2–3 gives more attention to explaining present conditions than past events.

The Eden narrative presents itself as an artistic adaptation of human type scenes and ANE symbols while subverting common cultural assumptions about God and his relationships to humans and their life upon the land. Thus, while the narrative does not present itself according to our Post-Enlightenment conception of history, that is, a critical and verifiable description of concrete events, it does present itself as a powerful dramatization of the human condition—as true from primeval times to the present.

► If we use later biblical interpretations of the Eden narrative as an interpretive guide to its genre, they read it as symbolic and typological narrative.

Info Box 10.6: The Garden of Eden elsewhere in the OT

If we seek out other OT passages that might serve as commentary on Genesis 2–3, we discover that the principal texts referring to “Eden” in the OT offer symbolical/mythological interpretations. In Ezekiel 28:11-19 God instructs the prophet to lament over the current king of Tyre: “you were in Eden … an anointed cherub” (Ezek 28:13–14). This judgment oracle even contains a “fall narrative” including expulsion: “You were blameless in your ways from the day that you were created, until iniquity was found in you. In the abundance of your trade you were filled with violence, and you sinned; so I cast you as a profane thing from the mountain of God, and the guardian cherub drove you out from among the stones of fire” (Ezek 28:15–16). In Ezekiel 31 “all the trees of Eden envied” the historical empire of Assyria, which is likened to “a cedar in Lebanon” (Ezek 31:1). This tree was similarly to be “cast out” because of pride (Ezek 31:10–11). When it is finally “cast down to Sheol … all the trees of Eden … were comforted” (Ezek 31:16). (See also Isa 51:3; Ezek 36:35; Joel 2:3.)

Info Box 10.7: Adam in Romans 5

The apostle Paul interpreted Adam typologically as “a type [typos] of the one who was to come” (Rom 5:14). The so-called doctrine of “original sin,” however, began, not with Paul, but with Augustine. He read the New Testament in Latin, not the original Greek. A literal translation of the key verse in Greek reads:

Therefore, just as through one man sin came into the world and through sin came death, and thus to all men death came, in that all sinned (Rom 5:12).

Thus, instead of the Greek phrase ἐφʼ ᾧ, which should be translated “in that all sinned,” Augustine read “in quo,” which he interpreted as “in whom all sinned,” that is, Adam. Hence, as Joseph Fitzmyer, a renowned NT scholar, says, “There is actually no teaching about a “Fall” in Jewish theology … ‘Original Sin’ is a Christian idea … When Augustine opposed Pelagius, who had been teaching that Adam influenced humanity by giving it a bad example, he introduced the idea of transmission by propagation or heredity” (Romans: A New Translation With Introduction and Commentary (Anchor Yale Bible 33; New Haven/London: Yale University, 2008), 409).

Paul’s exposition of universal human sin—his “fall story”—appears in Romans 1:18–32. It begins not with Adam, but with human behavior in general, especially the tendency to idolatry. Humans are culpable before God, not because of Adam’s transgression, but because of their persistent refusal to acknowledge God.

For what can be known about God is plain to them, because God has shown it to them. Ever since the creation of the world his eternal power and divine nature, invisible though they are, have been understood and seen through the things he has made. So they are without excuse; for though they knew God, they did not honor him as God or give thanks to him, but they became futile in their thinking, and their senseless minds were darkened. Claiming to be wise, they became fools; and they exchanged the glory of the immortal God for images resembling a mortal human being or birds or four-footed animals or reptiles (Rom 1:19–23, NRSV).

Paul’s exposition of “the fall” and its progression continues with a threefold phrase, “therefore God gave them up …” (Rom 1:24, 26, 28).

Info Box 10.8: An Interpretation from Second Temple Judaism

“For, although Adam sinned first and has brought death upon all who were not in his own time, yet each of them who has been born from him has prepared for himself the coming torment. And further, each of them has chosen for himself the coming glory…. Adam is, therefore, not the cause, except only for himself, but each of us has become our own Adam” (2 Baruch 54:15, 19).

10.4. Seven-Day Creation (Gen 1)

► To our surprise Genesis 1 begins with the earth, the darkness, and the deep in disorder—a theme familiar to ancient Semites.

As any text must be interpreted within its context, we will interpret the Seven-Day Creation account in Genesis 1:1–2:4a by examining it within its expanding contexts: its literary structure, its role in the Priestly strand of the Pentateuchal sources (P), its ANE context, and then its wider biblical context.

Starting Point and Structure. The seven “days” of creation indicate the narrative’s structure. The “tense” (or more accurately, verbal aspect) of the Hebrew verbs indicate that Genesis 1:1 is a summary statement for Genesis 1:1–2:4a. Genesis 1:2 begins the detailed narrative by setting the stage for the six days of God’s creative decrees.

1. In the beginning God created [perfective] the heavens and the earth.

2. Now the earth was [perfective] willy-nilly [tohu vabohu] and darkness was upon the face of the deep, and the wind of God was hovering over the face of the waters.

3. And then God said [vav-consecutive], “let there be light,” and there was [vav-consecutive] light.

4. And then God saw [vav-consecutive] …

Contrary to modern expectations, the opening stage is not empty: there are the earth, the darkness, and the deep/waters, over which the Spirit/wind/breath of God hovers. But this would not be contrary to ancient Semitic expectations, where the prevailing conception of deity and world order was expressed in the story line of divine cosmic kingship. If the Hebrew writer wanted to assert that his God is indeed the king over the cosmic powers and make it comprehensible within his Semitic culture, then he would need to testify that his God was the one who established order over the chaotic forces of the waters. As in the West Semitic “Baal Myth” and in the East Semitic “Enuma Elish,” the god of the skies battles the god/goddess of the seas for supremacy. Once the god of the storm is victorious, he is acclaimed king of the gods and his palace/temple is constructed on a sacred mountain. While the entities on this stage are similar in Genesis 1, their characterizations and relationships are markedly exceptional. Disorder is evident: “now the earth was willy-nilly” (Hebrew tohu vabohu). But the deep/waters are simply objects, not divinized or manifestations of deity, and “the wind of God” is not a weapon against the waters—it simply “hovers/flutters” over them. The narrative echoes the generic features familiar to its Semitic audience, only to overturn common Semitic expectations. On three occasions God names something (Days 1–3), and in each case it relates to one of the pre-existing entities: “darkness” he calls night (Gen 1:5), the firmament that separates the “waters” he calls skies/heavens (Gen 1:8), and the dry land he calls “earth” and the gathered “waters” seas (Gen 1:10).

Info Box 10.9: “Create” out of nothing?

Many readers assume Genesis 1 teaches what theologians call creatio ex nihilo. While this is a biblical doctrine (see below), it is not the starting point of Genesis 1. Some might suppose that the Hebrew verb “to create” entails creation out of nothing. While the verb is always predicated of God, its usage elsewhere indicates that it means “to do something unprecedented” (see esp. Num 16:30; Jer 31:22).

The first three days form a parallel structure with the second three:

Form/Space/Separation Fill/Creatures/Population

1 Said → Light (good) 4 Said → sun, moon, stars (good)

2 Said → Waters above firmament 5 Said → Birds

Waters below firmament (!) Fish (good)

3 Said → Land and water (good) 6 Said → Animals (good)

Said → Vegetation (good) Said → Humanity (all very good)

7 Sabbath

► Genesis 1 presents a parallel structure of the creation of spaces and then of the creatures that fill those spaces, climaxing in the Sabbath.

During the first three days God creates spaces by separation, and in the second three days he populates the corresponding spaces with creatures/entities. Days three and six each have two creative words. Each day is declared good, with the exception of the second, which is Monday! Particularly puzzling for modern readers is the creation of sun, moon, and stars after the creation of the earth’s clouds and oceans, land and vegetation. But this feature will become comprehensible once we consider the ancient Semitic perspective below. The day that stands apart from this parallel structure is the climactic seventh day, the Sabbath.

Readers often assume that the creation of humans forms the narrative’s climax, and that their creation “in God’s image” should be central to the Bible’s theological anthropology. But any OT reference to the image of God disappears after Gen 9:6. On the other hand, the single issue of Genesis 1 that gets the most attention throughout the OT canon is Sabbath: in the Pentateuch, the Historical Books, and the Prophets. It is of particular interest in exilic and postexilic books: Ezekiel, 1–2 Chronicles, Nehemiah, and the Priestly strands within the Pentateuch (embedded in Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers). Most significantly, Genesis 1 is the passage that informs us when Sabbath begins and ends: “there was evening and there was morning.”

► A close reading of Genesis 1 reveals its priestly fingerprints, whereby it sets the stage for Israel's liturgical calendar and food laws.

The Priestly “Agenda” of Genesis 1. Contrary to modern expectations, the Genesis 1 account focuses on a different agenda than detailing the means and sequence of the creation event. A close reading reveals a special connection to the vocabulary and themes that are important to priestly literature, such as Sabbath. The principal function of the lights/lamps created on day four is “for signs and for seasons/appointed times and for days and years,” that is, to establish the calendar and the liturgical calendar in particular. Sabbath was to be a perpetual “sign” of the weekly cycle that Israel was to observe as a confirmation that God had consecrated them (Exod 31:13, 17; Ezek 20:12, 20). The same Hebrew word rendered as “seasons” in Genesis 1 is translated as “appointed festivals” in priestly liturgical texts (Lev 23:2, 4, 37, 44; Num 10:10; 15:3; 29:39; Ezek 36:38; 44:24; 45:17; 46:9, 11). Outside of Genesis, reference to the “kind/species” of animals appears in the dietary regulations of Leviticus 11 (Lev 11:14–16, 19, 22, 29; cf. Deut 14:13–15, 18), where the Israelites are to “make a distinction” [the same Hebrew verb rendered “separate” in Gen 1: 4, 6–7, 14, 18] “between the unclean and the clean and between the creature that may be eaten and the creature that may not be eaten” (Lev 11:47; cf. 10:10; 20:24–26). In other words, judging by the echoes found elsewhere in the Bible, the principal function of Genesis 1 is to lay the foundation for Israel’s liturgical and dietary observances. The terminology of Genesis 1:1-2:4a aligns with that found in other ritual texts concerning Sabbath observance and festivals (Exod 20:8-11; 31:12-17; Lev 23) and clean and unclean foods (Lev 11).

Genesis: "On the seventh day God rested from all his work" (Gen 2:2-3).

Ritual: "On the seventh day you shall not do any work" (Exod 20:8-11).

"On the seventh day is a Sabbath of solemn rest... You shall not do any work... From evening to evening you shall observe your Sabbath" (Lev 23:3, 32).Genesis: Heavenly lights are "for signs ... and for days" (Gen 1:14).

Ritual: Sabbath observance is a "sign" (Exod 31:13, 17).Genesis: Heavenly lights are "for appointed times [mow'adim]" (Gen 1:14).

Ritual: "These are the appointed times/festivals [mow'adim] of Yahweh" (Lev 23:2, 4, 37, 44).Genesis: God orders creation by "separating" entities (Gen 1:4, 6-7, 14, 18) and by making each plant and creature "according to its kind" (Gen 1:11-12, 21, 24-25).

Ritual: Leviticus lists creatures according to their "kind" (Lev 11:14-16, 19, 22, 29) to "separate between the unclean and the clean" for dietary purposes (Lev 11:47).

(The connections between Genesis 1 and these ritual texts would have been more self-evident in the original Priestly document of the P source, before its combination with the JE narratives in Genesis–Numbers.)

The seven-day account of Genesis 1 provides a theological basis for Israelite rituals. Israel honors their Creator by resting on the seventh day because he declared it “holy” (Gen 2:3; Exod 20:8, 11; 31:14–15; Lev 23:3; cf. Lev 11:44–45).

So what does the text mean when it says, “And he rested on the seventh day from all his work which he did” (Gen 2:2-3)? This wider context of the Pentateuch sheds light.

“In six days Yahweh made the heavens and the earth and on the seventh he rested and took a breather” (Exod 31:17), just as “the son of your servant woman and the sojourner may take a breather” on Sabbath (Exod 23:12).

Does God, in fact, really need to do “work” for six days and then “rest” and “take a breather” on the seventh, like humans? Isaiah 40:28 speaks very much to the contrary.

In light of this wider OT context, the seven-day creation account speaks anthropomorphically about God in order to explain Israelite ritual. The “days” of God’s “work” and the notion of God “resting from all his work” are anthropomorphic depictions to provide a model for how Israelites are to observe Sabbath and honor the Creator. It would be inappropriate to read this account as a literal description of God’s “working” six “days” and “resting” on the seventh. (When the Bible uses the anthropomorphism, "The Lord is my shepherd" [Ps 23:1], most readers do not assume God uses a literal "staff" to protect his sheep.)

Genesis 1 should be read in the context of ritual. How did Israel know that Sabbath is to be observed on the seventh day and begins at sundown? Because of the seven-day account in Genesis 1.

► Genesis appears to mimic and then overturn the Babylonian Enuma Elish, which the Jews would have overheard during their exile in Babylon.

Genesis 1 as Countertext to “Enuma Elish.” As noted above, the Priestly document likely stems from the exilic period of Judah’s history, when their leaders and scribes resided in Babylon. To grasp the full significance of Genesis 1 readers should try to imagine its original historical and social setting in the exile. The kingdom of Judah had failed twice in its declarations of independence against the Babylonian Empire. In 586 BCE Nebuchadnezzar’s army destroyed Jerusalem and Yahweh’s temple, and forced a substantial portion of Judahites to migrate to Babylon. According to the ground rules of their shared Semitic culture, one would assume that Marduk, the patron deity of Babylon, vanquished Yahweh, Judah’s patron deity. Now living under the shadow of empire, the exiles would have been intimidated by the massive city of Babylon, along with its processional highways for the gods to be paraded to their temples. On the fourth day of the Akitu Festival, the myth, Enuma Elish, was recited to explain the rise of Marduk as king in the divine pantheon. Given this contact, it should not surprise us that Genesis 1 has significant parallels with the Enuma Elish (more so than the older Atrahasis Epic, which parallels Genesis 2). The Genesis 1 account mimics and yet overturns Enuma Elish by making the profound and counterintuitive claim that true Deity (’elohim) is not located in Babylon, nor even in Jerusalem. In fact, he does not need a temple or sacred space. Instead, he establishes sacred time. As such, he could still be worshiped by the Judahites, even in exile, through the rite of Sabbath observance.

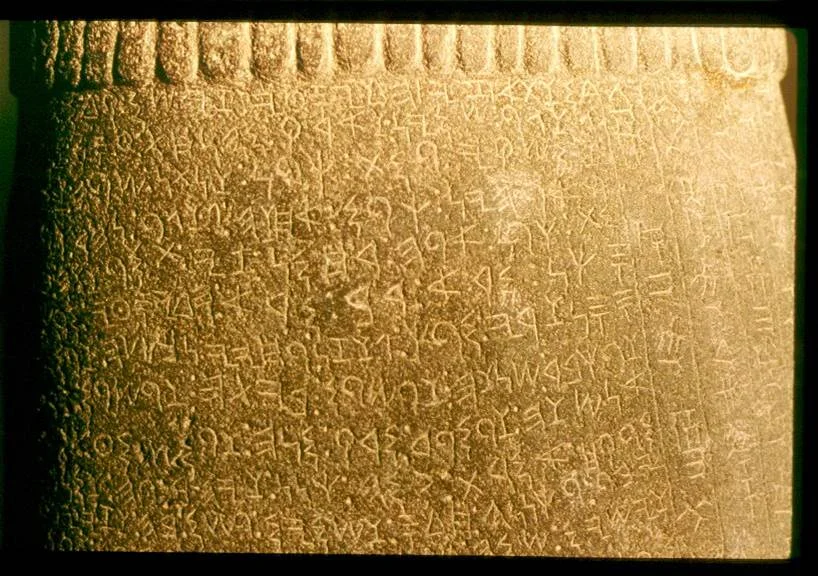

A tablet from Enuma Elish discovered in Ashurbanipal's Library

Info Box 10.10: Enuma Elish

This myth, at least as old as the 12th century BCE, explained the rise of Marduk, the patron deity of Babylon, as king in the divine pantheon. The text would have been recited on the fourth day of the Akitu Festival in Babylon.

It begins with a “theogony,” that is, the birth of the gods by the primal couple Apsu (abyss of fresh water) and Tiamat (salt water), whose waters commingle. The noise of the younger gods deprives Apsu of sleep, who decides to “silence” them. Tiamat opposes the plan. The stage is now set for a battle between younger and older gods. In the first battle Ea (god of streams/wisdom) kills Apsu after casting a sleeping spell.

Tiamat then seeks revenge—with Kingu as her commander. In the second battle Ea and Anu (sky-god) are repelled. A divine assembly appoints Ea’s son, a young god, Marduk (storm god) as king. In the third battle Tiamat appears as a sea monster who opens wide her mouth to swallow Marduk. As the storm god, “he released in her face” “the ill wind he had held behind him,” which “bloated her belly.” He then “shot off the arrow” (i.e., lightning), which “pierced the heart.”

An early second-millennium B.C.E clay plaque depicting Marduk splitting Tiamat open

Now midway through the myth there appears a “cosmogony,” that is, the creation of the cosmos. Marduk “split her in two, like a fish for drying, half of her he set up and made as a cover, heaven. He stretched out the hide and assigned watchmen, and ordered them not to let her waters escape. He crossed heaven and inspected (its) firmament.” From her body he forms the sky and seas, organizes the stars and moon, whose purpose is to “mark” the 12 months of the year.

After the gods acknowledge Marduk as their king, he resolved to “create humankind” to “bear the gods’ burden that those may rest.” Taking Kingu, Tiamat’s commander-in-chief, “from his blood he made mankind, he imposed the burden of the gods and exempted the gods.”

In gratitude the gods build a temple and a ziggurat in Babylon. Enlil, the former ruler of the gods, bestows on Marduk the lordship of the universe. The myth closes with Marduk’s fifty honorific titles.

► These ancient echoes help us moderns understand why Genesis 1 begins with disorder, refers to a firmament, and orders the sun, moon, and stars after the earth and the firmament.

Given the bizarre synopsis of Enuma Elish above, one may wonder, “So where exactly does this myth parallel Genesis 1?” Indeed, the civil war among the gods that dominates much of the myth’s plot is reduced to a brief reference to chaos: “now the earth was willy-nilly” (Gen 1:2). The parallels are related more to theology and worldview than to plot details, and they actually help explain some of the anomalies within Genesis 1 for modern readers. As already noted, particularly puzzling in Genesis 1 is the creation of sun, moon, and stars (day 4) after the creation of the earth’s clouds and oceans (day 2), and its land and vegetation (day 3). Its most significant echoes with Enuma Elish appear on days 2 (firmament), 4 (stars and the moon), and 6 (humanity), following the same sequence. In both accounts, one of the first acts of creation is the separation of waters, those in the skies from those in the oceans, by the construction of a “firmament,” that is, a solid dome to secure the waters above (day 2). Contrary to some modern English translations, an “expanse” (i.e., the vertical expanse of the atmosphere) is not a legitimate rendering of this Hebrew word, raqia‘, which denotes a metal plate that is beaten/hammered out (rq‘, i.e., the horizontal expanse of a metal dome; cf. Job 37:18). In both accounts, once the waters have been separated and secured, the stars and the moon are created for the purpose of marking the appointed times of the annual calendar—as both texts are foundational to the ritual observances of their respective peoples (day 4). The Genesis 1 account is explicit that the heavenly lamps are set “in the firmament” (Gen 1:14, 15, 17). Clearly, the firmament is a prerequisite for the sun, moon, and stars because that is the object that fixes them in the skies above.

► Genesis functions as polemic, arguing that God is one, nature is demythologized, and humans are created as God's agents to rule over nature.

Yet, while the constellations mark the likenesses of the great gods in Enuma Elish, they are simply “lamps” in Genesis 1. Sun and moon are not even named, perhaps because their names in Hebrew (shemesh and yārēaḥ respectively) echo the names of the corresponding Semitic deities (e.g., Akkadian Shamash and Ugaritic Yariḫu). And the stars, so significant to the Babylonians, are mentioned as a virtual afterthought in Genesis 1:16. Herein lies the most radical departure of Genesis 1 from Semitic theology and worldview: monotheistic theology and demythologized nature. On stage there is only one deity, Elohim, so there is no cosmic battle among the gods. The sun, moon, and stars are not divinized manifestations of separate deities; they are simply objects of God’s manufacture. They are not “he” and “she” gods to be feared and worshiped; they are “its,” which God deems “good.” In the language of the New Testament, Genesis 1 strips “the principalities and powers” of their fearful grip on humanity.

While both accounts mark the creation of humanity as distinct, Marduk resolves to create humanity “to bear the gods’ burden that those may rest.” He proposes to Ea, his wise father, “I shall compact blood, I shall cause bones to be.” Ea then advises Marduk of a plan to bind the god who incited Tiamat to wage war on the younger gods: “Let him be destroyed so that people can be fashioned.” A trial is convened, and Kingu is found guilty. Then “they imposed the punishment on him and shed his blood. From his blood he made mankind, he imposed the burden of the gods and exempted the gods.” Enuma Elish thus has a ready answer for the problem of evil and why humans act so violently towards one another: they were made from the blood of a god who wages war on his own kind. By contrast, God creates humanity to rule as virtual kings (Gen 1:26–28). Unlike both Enuma Elish and the Garden of Eden narrative in Genesis 1–2, no mention is made of the materials that God uses; he simply “created” humanity—most remarkably “in his image.”

The close reading above demonstrates that Genesis 1 was composed for an ancient Semitic audience. In this respect, modern interpreters read Genesis 1 as someone else’s mail. It was addressed to their concerns not ours. Hence, accurate interpretation of the Bible requires a fuller “translation” than one provided by English translations of the Bible. Modern readers must go beyond the translation of words and sentences and consider the further translation of concepts, symbols, and storylines that were inherent in the language and culture of the Hebrew Bible.

Chaos in Creation and “the image of God.”

And God said, “Let us make man in our image, according to our likeness, so they may have dominion over …

And God created the man in his image,

in the image of God he created him,

male and female he created them.

And God blessed them and God said to them, “be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth and subdue it and have dominion over … (Gen 1:26-28).

► As God's "image," humans represent God's royal rule over the creatures.

Given the Priestly background to this seven-day creation account, it may seem odd to suggest that anything in creation could reflect God’s “image” (ṣelem), especially as this term can be applied to idols (Num 33:52; 2 Kgs 11:18; Ezek 7:20; Amos 5:26). The term “likeness” (dĕmût), however, appears in one other biblical book in reference to God. Ezekiel, a priest, has a profound vision in which he sees enthroned “a likeness like a human appearance,” which he later describes as “the appearance of the likeness of the glory of Yahweh” (Ezek 1:26, 28). Clearly, Ezekiel strives to maintain God’s transcendence in his vision: he does not see Yahweh himself, only the appearance of the likeness of his glory. He is thus very measured in his use of “likeness,” but the term “image” he uses only of idols (Ezek 7:20). The juxtaposition of “image” and “likeness” in reference to God is difficult to explain within the OT itself. Fortunately, a recent archaeological discovery may help clarify the meaning of these expressions.

Info Box 10.11: Tell Fakhariyeh Statue

The Tell Fakhariyeh statue (mid-9th BC) commemorates the installation of the king's statue in the temple of the god Hadad of Sikan

In 1979 a farmer uncovered what came to be known as the Tell Fakhariyeh statue in Syria, along a branch of the Habur River just south of the Turkish border. The mid-ninth century BCE king, named Hadad-yithʿi (which means “Hadad is my salvation,” comparable to Isaiah, “Yahweh is salvation”) had installed the statue of himself in the temple of the god Hadad of Sikan. Upon his skirt was inscribed a bilingual text, first written in Assyrian cuneiform and then in Aramaic.

“This is the likeness [dmwtʾ] of Hadad-Yithʿi which was placed before Hadad-Sikkan” (line 1).

“Before Hadad who dwells in Sikkan, the lord of Habor, he placed his image/statue [ṣlm]” (lines 15–16).The term “likeness” introduces the section where the king serves as supplicant to the deity. “Image” introduces the section where he serves as governor to the people. The statue thus serves a mediating role between the king’s rule of his people and his god.

Detail of Aramaic text

This shared Semitic context would indicate that the word pair image-likeness points to a royal symbol of a king, not a religious symbol of a deity. Thus, in Genesis 1 image-likeness does not denote a religious idol, representing a god to be worshiped in a temple, but a royal statue that mediates between deity and domain. Its function is not to act as an object of worship but as a representation of royal mediation, as expressly stated in Genesis 1:26: God makes humanity “in his image/likeness” to exercise his dominion over the earth.

► God created humans to carry on God's efforts to bring order to the "willy-nilly" disorder inherent in the world.

Why this exercise of dominion and subjugation is necessary was initially laid out in the verse that sets the stage for the whole narrative: “Now the earth was willy-nilly” (Gen 1:2). As the cosmic divine king, God’s project is to bring order to disorder, first by establishing the forms of light, a firmament, and land and water (days 1–3) and then by populating those spaces with creatures (days 4–6). Then, on this final day of creation God creates his representative to continue this royal task of ordering his creation. After this act of delegation to humanity on day 6, God rests on day 7!

This exercise of dominion is an ongoing task, thus implying that a measure of chaos continues to be inherent the system itself. This is its “default” state. It is restrained only by God’s ordering of creation and then by God’s delegation of authority and power to humanity. Left to itself, the nature of the earth, the darkness and the deep, is to remain in a disordered state—“willy-nilly.” Chaos still threatens and remains “at large.” Disorder is a given; order must be achieved now through God’s appointed agent of humanity. While creation is indeed a “very good” (Gen 1:31), there are no claims that creation is a perfect paradise or regulated system, where everything happens in an ordered fashion—with rhyme and reason.

The nature of God’s royal sovereignty in Genesis 1 is that of governance and delegation. The responsibility of bringing order to the world he has entrusted to humans. The question of God’s continuing work with humanity and the world is not addressed until the second creation account in Genesis 2–3.

Info Box 10.12: How important are the Primeval Narratives to the rest of the OT?

Elsewhere in the OT little is said of the creation themes mentioned in Genesis 1–3. For example, beyond the original references to the “image of God” in Genesis 1:26–27, the only other references are found in Genesis 5:3 and 9:6. Beyond the Primeval Narratives, human culpability is nowhere based on a single historical transgression whereby humanity moves from being “good” and innocent to being guilty and worthy of banishment. The sin of the man and the woman is nowhere presented as infecting or being inherited by humanity. In fact, both Deuteronomy and the Prophets are clear that intergenerational punishment is contrary to God's preferred form of justice (Deut 24:16; Jer 31:29-30; Ezek 18:1-32, which are discussed in later modules). The “creation-fall-redemption” sequence, so important to some Christian theologies, finds little place in the OT itself. Israelites are judged by God because of disobedience to God’s commandments, his covenant, and his prophets. Gentiles are guilty because of their acts of inhumanity (Amos 1–2; Hab 2).