Exodus

Canonical and Historical Context: Who’s on stage?

► As the Pentateuch is told from a Yahwistic perspective, Exodus forms the first chapter while Genesis sets the stage as a prologue.

If we think of the biblical “books” as a single volume anthology with a Table of Contents, we should regard the book of Exodus as "Chapter 1" and the book of Genesis as the “Prologue.” The defining moments of God’s formation of the people and their “constitution” lie in the book of Exodus, wherein God defines his role as Savior and binds himself to them in a legal contract. There he divulges to them his personal name, Yahweh, and his plan and values. In many respects, the book of Genesis sets the stage for these foundational events.

Outline and Key Passages

1–18 Egypt and exodus

1 Transition from Genesis: Pharaoh enslaves the Hebrews

2 Moses’ early years

3–4 Dialogue of Yahweh and Moses at the burning bush

5–6 Bricks without straw and the second dialogue

7–10 Moses’ confrontations with Pharaoh and the nine plagues

11–15 Passover and the exodus from Egypt

16–18 Murmurings en route to Sinai

19–40 Sinai and covenant

19 Narrative: Arrival at Sinai

20–23 Covenant Code

24 Narrative: Covenant ceremony

25–31 Instructions for the tabernacle and priesthood

32–34 Narrative: Golden Calf

35–40 Instructions for the tabernacle and priestly garments

The book of Exodus falls into two distinct parts. The first consists primarily of narrative material where Moses is the central character, especially in his private dialogues with Yahweh, his advocacy before Pharaoh in the plague narrative and his agency at the Reed Sea deliverance. Regulations regarding the Passover ritual interrupt the story about the tenth, climactic plague. The narrative in the second half recounts the arrival at Mount Sinai and the covenant ceremony between Yahweh and the people. After Moses’ 40-day absence on the mountain, the people worship a golden calf (or young bull), provoking a crisis which is resolved during Moses’ third dialogue with Yahweh. Interwoven with these narratives are the laws of the Covenant Code and the instructions for the construction of the tabernacle and the priestly garments.

Situation and Message: What’s at Stake?

► Exodus provides little historical information, such as the identity of Pharaoh and the location of Sinai.

Given the importance of the Hebrews’ exodus out from bondage in Egypt, it seems odd that the Bible gives little historical information when it took place. Nor are we certain of the geographic location of Mt. Sinai. Throughout the book of Exodus “Pharaoh” is unnamed—in contrast to the later historical narratives in 1–2 Kings (Pharaoh Shishak is named in 1 Kgs 11:40; 14:25, Tirhakah in 2 Kgs 19:9, and Neco in 2 Kgs 23:29–35). (The difference may lie in the existence of a scribal class, employed by the monarchy, that records detailed, written accounts of historic events. This observation may imply therefore that the book of Exodus contains “prehistoric” material, that is, oral traditions.) We may be given a hint in Exodus 1:11, which records that the Hebrews were enslaved to build “for Pharaoh store cities, Pithom and Raamses.” Ramesses II ruled Egypt in the 13th century BCE, a time that accords with other historical data. Indeed, an official of Ramesses II instructs the foreman at Pi-Ramesses: “Distribute grain rations to the soldiers and to the Apiru who transport stones to the great pylon of Ramesses” (Leiden Papyrus 348). The historicity of the exodus is certainly an important question, but its details are best investigated in connection with the conquest and settlement of the land, which is narrated in the book of Joshua.

The Hebrews in Egypt and the Exodus (Exod 1–18)

► Between Genesis and Exodus there are centuries of silence, and the transitional link in Exodus 1 is brief and gives no theological reason for the oppression of the Hebrews.

As we flip the page from the book of Genesis to the book of Exodus, we leap some 200–400 years in history. The book of Genesis closes with Joseph’s promising words: “God will indeed attend to you and bring you from this land [of Egypt] to the land that he swore to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob” (Gen 50:24). The book of Exodus opens with a list of Jacob’s sons who migrated to Egypt in the closing chapters of the book of Genesis (Exod 1:1–6). The transitional narrative covering the intervening centuries is very brief: Israel’s descendants multiplied and “there arose a new king over Egypt who did not know Joseph” (Exod 1:8). As we saw the book of Genesis, the editors of these biblical books have compiled traditions that were originally separate. The Bible does not present us with an unbroken chain of stories from one generation to the next.

While the book of Exodus headlines God’s intervention in liberating his people from slavery in Egypt, it does not provide any insight as to why he allowed his people to fall into slavery in the first place. The reasons given for Pharaoh’s oppression of the Hebrews are entirely historical and social, not theological (Exod 1:8–22). As the new Pharaoh felt no loyalty to Jacob’s descendants, he exploited them for fear they might ally with Egypt’s enemies.

Info Box: Ancient Biblical Manuscripts with Different Chronologies

According to the Hebrew Masoretic Text (MT), "the dwelling of the sons of Israel in which they dwelt in Egypt was 430 years" (Exod 12:40). But according to the Greek Septuagint (LXX), the 430 year period marks their stay "in the land of Canaan and in the land of Egypt," thus including both the Ancestors’ sojourns in Canaan and Egypt (Gen 12–50) and the Hebrews' residence in Egypt (Exod 1-12).

► While reading the Bible, we must observe both contents and form. The dialogues between Moses and Yahweh are telling about how Yahweh interacts with people. Verbs drive the plot and character development.

The dialogues between Moses and Yahweh (Exod 3–4; 6). The first half of the book of Exodus is ultimately about the Hebrews’ oppression and liberation from the land of Egypt, but—like a good movie—the biblical narratives personalize the story by placing the figure of Moses center stage, along with his antagonist, Pharaoh. Particular focus is given to the dialogues between Moses and Yahweh and secondarily to the confrontations between Moses and Pharaoh. This is not simply a historical account of a people’s socioeconomic liberation. It includes insights on the divine-human encounter, especially concerning intercession and negotiation. Arguably, the most significant conversation of the whole Bible is the “burning bush” dialogue (Exod 3:1–4:17). Strange as it might sound, the instrument by which God manifests his presence (as “the angel of Yahweh”) is a mere bush, a briar/bramble bush in particular. Perhaps not coincidentally, its name in Hebrew, seneh, is very similar to that of the sacred mountain Sinai (sînay).

Mosaic of Moses at the Burning Bush (St. Catherine's Monastery)

As sacred literature, readers must consider not only the Bible’s contents but also its literary form. In addition to what is said we should respect how it is said. Some of the OT’s most profound and foundational theological disclosures occur in dialogue, even where the human figure initiates the conversation with a prompting question. In fact, we would not know God’s personal name, Yahweh, were it not for Moses’ inquiry. Theology—in the Hebrew Bible—is often delivered through dialogue, not simply through monologue, decree, or pronouncement. Divine revelation is not simply dropped from heaven; it is a tapestry woven with divine and human threads.

After summoning Moses, God identifies himself by the old epithet, the God of the ancestors: “I am the God of your father, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob” (3:6).

And Yahweh said, “I have indeed seen the affliction of my people in Egypt and their cry I have heard on account of their taskmasters because I know their pains. And I have come down to deliver them from the hand of Egypt and to bring them up from that land to a good and spacious land … (Exod 3:7-8, J)

And now the outcry of Israelites has come to me and I have also seen the oppression with which the Egyptians are oppressing them. And now go so I may send you to Pharaoh and bring my people the Israelites out from Egypt (Exod 3:9-10, E).

Exodus 3:7–10 exemplifies how the Hebrew Bible packages its theology: it does so through narrative and verbs, as distinct from systematic theology, which does so through theological discourse and nouns and adjectives. God is not described by concepts and states of being, but rather as a literary character in action. While he is not explicitly defined here as omniscient, he sees, hears, and knows. While he is not identified as omnipotent, he will deliver his people from the greatest superpower of that time. Moreover, with the splicing together of these originally separate strands, the editor has formed an echo, similar to Hebrew poetic parallelism. But God does not simply repeat himself between verses 8 and 10: we see a profound juxtaposition of divine sovereignty and human agency.

► Moses raises four objections to God's plan, to which God responds with promises, not anger.

At the burning bush God does not shun questions and objections. Evidently, God's messengers are best suited when they are not simply passive recipients of divine instructions but are eager partners in conversation. We also observe the Bible's honesty regarding the frailty of its "heroes."

At the burning bush Moses raises four objections to God’s plan and in particular to his choice of agent. Each time God responds, not with rebuke or frustration, but with a new reality of faith. The first and last raise questions about Moses’ personal qualifications. First, Moses expresses doubts about his social position: "Who am I that I should go to Pharaoh, and bring the Israelites out of Egypt?" (emphasis mine). While this is directly a question about Moses, he also implicitly questions God's choice of agent. God's response is telling: "I will be with you.” He sidesteps the issue of Moses’ self-identity and makes no attempts to bolster his self-esteem. Instead, he simply draws Moses’ attention to God's presence with him. He is the factor that makes all the difference. In his fourth objection, Moses raises doubts about his personal competence: "O my Lord, I have never been eloquent, neither in the past nor even now that you have spoken to your servant; but I am slow of speech and slow of tongue” (Exod 4:10). Once again, Yahweh ignores the issue of Moses' talents or lack thereof, and points back to himself: "Who gives speech to mortals? Who makes them mute or deaf, seeing or blind? Is it not I, the LORD? Now go, and I will be with your mouth and teach you what you are to speak” (Exod 4:11-12).

After this fourth objection Moses says, "O my Lord, please send someone else.” It is this final dodge that kindles "the anger of the Lord" against Moses. To his earlier questions and concerns Yahweh responded with greater theological revelation, but this final evasion Yahweh answers with anger. Yahweh is certainly open to hearing doubts and hesitations, but the refusal of one’s will is another matter. As a concession, Yahweh appoints Aaron as spokesperson (Exod 4:14-16).

► During the conversation God enigmatically reveals his personal name, Yahweh, which is forever associated with the exodus deliverance.

Moses's second and third hesitations concern the likely response of his fellow Hebrews in Egypt and their doubts about this divine visitation. His second question, conveniently put in their mouth, probes the level of Moses' intimacy with this God: "If I come to the Israelites and say to them, 'The God of your ancestors has sent me to you,' and they ask me, 'What is his name?' what shall I say to them?" Their thinking would be, if you have encountered God, you should know his name. Moses needs insider information, and Yahweh complies by revealing the divine secret of his personal name. (Also significant is that it is here that Yahweh provides the most detailed instructions about what Moses should do next.) The Hebrews' question also probes the particular identity of this God. Names in ancient Semitic cultures were not mere labels; they often conveyed a telling message, sometimes highlighting a key characteristic related to the identity of the name-bearer. God discloses an enigmatic answer: "I am who I am…. Thus you shall say to the Israelites, 'I am has sent me to you.'"

Info Box: Personal Names and Their Meaning

Isaac (יִצְחָק) means "he laughs." Isaiah (יְשַׁעְיָהוּ) means “Yah(weh) is salvation.” Note esp. the sign-names of the children in Isaiah 7-8: Shear-jashub (שְׁאָר יָשׁוּב, “a remnant will return"), Immanuel (עִמָּנוּ אֵל, “God is with us"), and Maher-shalal-hash-baz (מַהֵר שָׁלָל חָשׁ בַּז, “speedy spoil, hasty prey”). The same is true of many divine names. El Elyon (אֵל עֶלְיוֹן) in Gen 14:18-22 means "El/God Most High." Baal, as he was known in Canaan and at Ugarit, means "Lord.” Hadad, as he was known in Syria, means “Thunderer,” that is, the storm-god.

While God answers the question, he is also being elusive. What after all does the enigmatic “I am” mean? We should first note that this "I am" declaration occurs in close context with several other "I am" statements: "I am/will be with you" (Exod 3:12) and "I am/will be with your mouth" (Exod 4:12, 15). God’s “I am” could thus point to both his existence and his presence with his agents. Later, in Exodus 33:19 God makes another proclamation of his name “Yahweh” (“I will call upon the name Yahweh before you”), and does so using a similar sentence structure formed by complementary phrases around the relative pronoun “who”:

“I will be gracious with whom I will be gracious,

and I will show compassion with whom I will show compassion.”

“I am who I am.”

While this proclamation may sound redundant, in context Yahweh is affirming his independence and sovereignty to determine his own choices. In other words, “I, not you Moses, decide to whom I will show mercy.” Hence, “I am who I am” should likely be heard as a statement of independence. In other words Yahweh says, “while I am giving you my name, I am not giving myself away.”

In connection with these "I am" statements, God discloses his personal name: "Thus you shall say to the Israelites, Yahweh, the God of your ancestors, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, has sent me to you': This is my name forever, and this my invocation name for all generations” (Exod 3:15, my translation). The deity worshiped by Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob here discloses his personal name, Yahweh. He is not simply a divine being, God, nor does he simply have a title, Lord. His personal name underscores his personal character and his personal interaction with the Hebrews in particular.

There is a word play between God’s personal name, "Yahweh" (yhwh) and the Hebrew verb, "to be" (hyh, or in its more primitive form, hwh). This is not an etymology of the divine name, as the connection between “I am” and “Yahweh” is not direct. Nowhere else in the Bible is any significance attached to a connection between Yhwh and the Hebrew verb “to be.”

Of particular significance is the close association between “Yahweh” and the exodus liberation. When Moses first publicly announces to the Israelites that the name of the God of their fathers is Yahweh, Yahweh here declares that he knows their plight in Egypt and promises to bring them up out of Egypt to another land (Exod 3:16–17). Thereafter and throughout the Law, Psalms, and the Prophets he will be known as “Yahweh your God who brought you out from the land of Egypt” (Exod 20:2; Lev 26:13; Ps 81:10; Hos 12:9; 13:4; Ezek 20:5, 9). The name of Yahweh will always ring in the ears of the Israelites as a name of liberation.

Moses obeys God and returns to Egypt to declare Yahweh’s demands to Pharaoh. But matters get worse. Pharaoh now forbids the Egyptian taskmasters from supplying the Hebrew slaves with the straw needed for brick production while insisting they produce the same quota of bricks. A second dialogue ensues, one with themes similar to the burning bush episode, except that Moses initiates this conversation. He complains in no uncertain terms: “Lord, why have you done evil to this people? Why did you send me? From the moment I came to Pharaoh to speak in your name he has done evil to this people, but you have not in fact delivered your people.” Although Pharaoh is clearly to blame for Israel’s plight, Moses alleges that Yahweh is ultimately liable and negligent. To our surprise, God does not dismiss Moses as insolent. Rather, he reiterates his promises and the connection between his name, Yahweh—repeated 5 times—and the upcoming exodus. In this respect, he stakes his divine reputation on delivering his earlier promises. This divine speech is the Priestly counterpart (P) to Yahweh’s disclosure of his name and the upcoming exodus at the burning bush (JE). Again, the theology of Yahweh is unpacked by verbal action, not theological descriptors. In addition to the common verbs of “bringing out” and “delivering,” Yahweh also promises, “I will redeem you,” which engages an economic metaphor of “reclaiming/buying back” often out of debt slavery. This passage highlights several priestly themes of its own by echoing Genesis 17 (also P) in particular. While Abraham had identified God as “God Almighty” (Gen 17:1), God is henceforth to be known by this new name “Yahweh,” ever associated with the exodus deliverance. God affirms his “covenant” with the ancestors to give them “the land” and his promise to be “their God” (Gen 17:7–8).

► The plague narrative portrays a contest between Pharaoh, who strengthens his resolve, and Yahweh, who publicizes his name.

Moses’ confrontations with Pharaoh and the nine plagues (Exod 7–10). A theme central to the plague narrative is the publication of Yahweh’s name, not only to the Israelites, but also to the Egyptians: “Egypt shall know that I am Yahweh when I stretch out my hand over Egypt and I will bring the Israelites from their midst” (Exod 7:5; cf. 8:22; 9:14, 16; 10:1–2). To promote this publicity Yahweh promises to boost the drama: “I will harden (qšh) Pharaoh’s heart” (Exod 7:3). The drama will be played out as an escalating contest between Yahweh, the hero, and his antagonist, Pharaoh. Such a characterization could be construed as manipulative, whereby Yahweh forces Pharaoh to do something he would not otherwise do. Indeed, most modern English translations give this impression. A closer examination of the Hebrew text, however, reveals a more subtle story. Wherever English translations refer to Pharaoh’s heart being “hardened,” three different Hebrew roots are used: to harden (qšh) is used once (Exod 7:3), to make heavy (kbd) is used 8 times, and “to strengthen” (ḥzq) is used 12 times. In most cases, the literal sense is that one’s heart is “strengthened,” or in today’s idiom, one’s resolve is strengthened. This conveys a considerably different portrayal than most English translations present. While Yahweh promises in advance that he will actively “strengthen Pharaoh’s heart” (Exod 4:21) or “harden Pharaoh’s heart” (Exod 7:3), in the unfolding narrative it is Pharaoh’s own heart that is “strengthened” (Exod 7:13, 22; 8:19; 9:7, 35) or that he deliberately “makes heavy” himself (Exod 8:11, 28; 9:34; cf. 7:14) during the first five plagues. Only during the sixth, eighth, and ninth plagues does Yahweh become the subject of the verb and take the initiative to strengthen Pharaoh’s resolve (Exod 9:12; 10:20, 27; 11:10; cf. 14:4, 8, 17) or to make his heart heavy (Exod 10:1). In other words, Pharaoh had initially made his own decision to refuse Yahweh’s demands. Only later does Yahweh push him to continue in his chosen course of action.

While not emphasized, the narrative does indicate that “also an ethnically mixed multitude went up with them” in the actual exodus out of Egypt (Exod 12:38), implying that many Egyptians were persuaded to join the Hebrews.

► The climactic plague strikes Egypt's firstborn and is commemorated in the Passover ritual.

The Tenth Plague and the Passover (Exod 11-13). The decisive plague is the tenth: death to the firstborn in Egypt. While explicit mention is made that the Israelites are automatically spared from several of the preceding nine plagues (Exod 8:22–23; 9:4, 26), such is not the case in this final plague. Exodus 12–13 contains at least two accounts of the required ritual (Exod 12:1–20, 43–51 = P, Exod 12:21–23 = J, Exod 12:24–27; 13:3–16 = likely a Deuteronomic supplement). Both agree that each Hebrew household is to slay a lamb and then to put its blood on the door posts and lintel. Yahweh will then pass through (‘br) the land of Egypt and strike its firstborn, but when he sees the blood he will “pass over” (pasaḥ) that household. For this reason the rite is called “Passover” (pesaḥ). As expected, the Priestly version offers more ritual details. After roasting it over a fire, they are to eat it—in its entirety—“with unleavened bread and bitter herbs” (Exod 12:8). In addition, “thus you shall eat it: with your waist belted, your sandals on your feet, and your staff in your hand. And you shall eat it in haste. It is a Passover for Yahweh” (Exod 12:11). The bread must be made without leaven or yeast so the ritual can reenact the haste with which the Egyptians urged the Hebrews to exit Egypt (Exod 12:33). In connection with the striking of Egypt’s firstborn, including human and animal, Yahweh declares, “upon all the gods of Egypt I will perform judgments,” thus highlighting the cosmic dimension of the conflict.

Both accounts also emphasize that this ritual is to be performed annually throughout the generations to commemorate this event as a memorial: “When your children say to you, ‘What is this service about for you?,’ You shall say, ‘It is a Passover sacrifice for Yahweh because he passed over all the houses of the Israelites in Egypt when he struck Egypt but our houses he delivered’” (Exod 12:26–27). Memory is a critical component of Old Testament faith. There is to be a seven-day festival to Yahweh that begins with the removal of leaven from the households and continues with the consumption of unleavened bread for each of the seven days.

The Priestly account, by calling a “holy assembly” on the first and seventh days (Exod 12:6, 16), anticipates when Passover will be observed as a pilgrimage festival at the central sanctuary. Similar to Sabbath observance, work is prohibited during the seven days. The penalty of excommunication is pronounced on anyone who consumes what is leavened (Exod 12:15, 19). Further regulations, concerning natives, foreigners, and sojourners, were apparently added later to the P account in Exod 12:43–51.

Using Deuteronomistic language (esp. Deut 6:7–8, 10, 20; Josh 1:8), Exodus 13:3–16 stipulates that, “when Yahweh brings you into the land …, which he swore to your fathers to give you …, you shall tell your son” the meaning of this festival. “And it shall be for you to as a sign on your hand and a memorial between your eyes, in order that Yahweh’s law may be in your mouth” (even though in the chronology of the book of Exodus, Yahweh’s law has yet to be presented!). This passage picks up a leitmotif of the Exodus narrative, namely the firstborn. After the burning bush dialogue, Yahweh gives Moses a message for Pharaoh: “Israel is my firstborn son.… Send out my son so he may serve me. If you refuse to send him, I will kill your firstborn son” (Exod 4:22–23). After Yahweh strikes Egypt’s firstborn and spares Israel’s, the firstborn of Israel now belong to Yahweh. But this passage here provides for their “redemption.” This rite is to serve as a personal reminder to each family unit that “by a strong hand Yahweh brought us out from Egypt.”

The meaning of “Passover” and its connection to the verb, here translated “pass over,” has been much debated among scholars. In other passages the verb generally means “to limp,” as in the case of Saul’s son, Mephibosheth (2 Sam 4:4), and the limping dance of the prophets of Baal around their altar (1 Kgs 18:26). Some scholars have suggested that the Jewish Passover could have been a creative reinterpretation of an earlier pagan ritual. In any case, it is clear that the principal function of the blood sacrifice is apotropaic, that is, a ritual to avert evil. The OT nowhere connects the Passover sacrifice with the atonement of sin.

The Exodus from Egypt (Exod 14–15). The English translation “Red Sea” (Exod 10:19; 13:18; 15:4, 22; 23:31) derives from the ancient translations of the Greek Septuagint and the Latin Vulgate. The Hebrew phrase, however, is “Reed Sea,” the same word used for the “reeds” along the riverbank from which the baby Moses was launched in a basket (Exod 2:3, 5). Although Red Sea could not be defined as a sea of reeds, there are other, suitable bodies of water, like the Bitter Lakes, between the mainland of Egypt and the Sinai Peninsula.

► In the prose account(s) of the Reed Sea crossing, the Israelites murmur and Moses is center stage as Yahweh's agent.

If Israel’s faith and indeed the identity of Yahweh their God were to be defined by a moment, the deliverance at the Reed Sea would be it. There are several accounts of the one event: the Song of the Sea in Exodus 15 and likely two others combined in the prose narrative in Exodus 14. In the prose version the Israelite’s character is frightened, forgetful, and blaming. In both versions Yahweh’s character appears as the God of the skies and a divine warrior fighting for Israel. While they cry out to Yahweh, Moses gets the blame: “Was it because there were no graves in Egypt that you took us to die in the wilderness? What is this you have done to us by bringing us out from Egypt? Was this not the word we spoke to you in Egypt, ‘leave us alone, so we may serve the Egyptians, where is better for us to serve the Egyptians and to die in the wilderness’” (Exod 14:11–12). The narrative sequence clearly implicates the Israelite’s failure of memory, thus forgetting Yahweh’s “signs and wonders” of the plague sequence. Moses’ response is unequivocal: “Fear not, take your stand and see Yahweh’s salvation which he will do for you today. For the Egyptians you see today you will never see again. Yahweh will fight for you, but you will be silent” (Exod 14:13–14). Only after “Israel saw the great hand that Yahweh used against the Egyptians” “did the people fear Yahweh and believe in Yahweh and Moses his servant” (Exod 14:31). In spite of their prior forgetfulness and disbelief, Yahweh intervenes. Their only correct behavior lies in their response of faith and singing with Moses a hymn praising Yahweh’s mighty deeds.

► In the hymnic account Yahweh is both "man of war" and God of the skies, who cast Pharaoh's chariots in the sea.

The Song of the Sea has two parts (Exod 15:1–12, 13–18). The focal point of the first is Yahweh’s name and identity: “Yahweh is a man-of-war; Yahweh is his name” (Exod 15:3). Just prior to this new designation he is identified with the old familiar epithet from the religion of the Ancestors, “the God of my father,” thus linking the old and the new understandings of God. The parallel phrase, “my God” is familiar from the old individual prayers found in the book of Psalms (e.g., Pss 13:3; 18:2, 6; 22:1–2, 10).

As a man-of-war, Yahweh achieves victory with his “right hand” (Exod 15:6, 12), but as a divine warrior the hymn recounts, “with the wind/breath of your nostrils the waters piled up” and “you blew with your wind; the sea covered them” (Exod 15:8, 10). Then in mythic personification, “the earth/underworld swallowed them” (Exod 15:12). This archaic hymn employs the well-known Semitic tradition of the God of the skies, best exemplified in the Baal myth discovered at ancient Ugarit. The first episode’s climax narrates the battle between the storm god, Baal, and the sea god, Yam. As soon as the storm god is victorious, there is the acclamation, “Baal reigns!” But in the Song of the Sea the characters are given a novel twist: Yahweh’s opponent is Pharaoh, and the sea/deeps/waters become his instruments of warfare. The poem includes a citation from Yahweh’s opponent to highlight his arrogance: “I will pursue, I will overtake, I will apportion the spoil, my soul shall have its fill of them” (Exod 15:9). In the Song of the Sea, West Semitic myth has been transformed into Hebrew epic (so Frank Cross, Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic). Once victorious, the hymn celebrates Yahweh’s divine incomparability and reign: “Who is like you among the gods?” and “Yahweh reigns forever and ever” (Exod 15:11, 18). Strange as it might sound, this rhetorical question works as praise only if “the gods” are regarded as real beings (“who is like you among the nothings?” would be damning with faint praise!). The theological perspective at this point is not monotheistic (belief in one God), but henotheistic, that is, belief in one superior deity among many divine beings.

The second half narrates Yahweh’s guiding of the people to his sacred mountain and sanctuary (Exod 15:13, 17), which from the narrative perspective of the book of Exodus is yet to unfold in the books of Joshua and beyond. Some scholars have suggested these verses represent a later insertion, though there is nothing to imply this in the poem itself. In fact, this episode is integral to the Semitic storyline of the God of the skies. Once the divine warrior becomes the divine king, he requires a palace/temple on his sacred mountain. In the myth’s second episode Baal celebrates “the holy mountain of my heritage,” which is very similar to the Song of the Sea, which praises Yahweh and “the mountain of your heritage,” where “your holy place” is established.

It is noteworthy that the hymn’s portrayal of the Israelite settlement of Canaan is in sharp contrast to that of the book of Joshua. In this case, the inhabitants and leaders of Philistia, Edom, Moab, and Canaan are so dismayed and immobilized that Yahweh’s people simply “pass by” (Exod 15:14–16). No military engagement is hinted.

Most scholars regard the Song of the Sea as one of the most ancient texts of the Hebrew Bible. The prose account of Exodus 14 was likely composed later. Their perspectives on the event differ. According to the hymn, “with the wind/breath of your nostrils the waters piled up, the flowing waters stood like a heap, the deeps congealed in the heart of the sea” (Exod 15:8). This description is very similar to the Israelites’ crossing of the Jordan River when the waters stood in a “heap” because the waters were dammed upstream (Josh 3:13, 16). In the exodus, one could imagine a tsunami, where the waters initially retreat only to return in a horrifying flood. The prose account contains two distinct explanations in a single verse (Exod 14:21). It is possible we are reading two originally separate strands woven into a single account. In the first half of the verse, “Yahweh made the sea go back with a strong east wind” (likely J), which conforms the poetic account. (The poem and the J strand are also in agreement how Yahweh dealt with the Egyptians by "throwing" them into the midst of the sea [Exod 14:27; 15:1].) In the second half of the verse, “the waters were divided,” so “the Israelites entered in the midst of the sea on dry ground and the waters to them were a wall on their right and on their left” (Exod 14:22, likely P). One wonders how both could be the case. If the east wind is sufficient to push the sea back, how could the Israelites walk against this unidirectional force that splits the waters? In any case, the woven narratives of this pivotal event are in agreement that Yahweh’s intervention is marked by the use of agents: a human agent to stretch the staff in his hand over the sea (Exod 14:16, 21) and a natural agent to push back the sea.

Mount Sinai (Exod 19–40)

Sinai Peninsula by satellite

► The Sinai narratives weave together three strands that highlight the covenant, the people's direct encounter with Yahweh, and his glory which summons Moses to receive the tabernacle plans.

Narratives (Exod 19; 24; 32–34). We will focus first upon the narrative material in chapters 19 and 24, before exploring the law code embedded in chapters 20–23, and then chapters 32–34, before exploring the instructions for the tabernacle’s construction. Upon their arrival at “the mountain,” Moses ascends to God, who gives him this message: Yahweh has brought them out of Egypt to himself, in order to establish a “covenant”: “if indeed you listen to my voice and keep my covenant, you shall be to me a prized possession among all the peoples, for all the earth is mine. And you shall be to me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation” (Exod 19:4–6). The people respond, “all that Yahweh spoke and we will do.” But after God appears in “a thick cloud” with “thunder and lightning”—in other words, in a theophanic appearance of the God of the skies—the people “trembled,” “quivered and stood afar off” (Exod 19:16–17; 20:18). This time they shrink back from any further direct encounter with God and implore Moses to be their mediator: “you speak with us and we will listen, but God should not speak with us lest we die” (Exod 20:19). Moses clarifies for them the meaning of the dramatic theophany: “don’t fear because God has come so that he may test you and that his fear may be before you so you not sin” (Exod 20:20). This paradoxical verse is very telling on the precise nuance of “fearing God” in the Old Testament. The phrase indeed denotes fear in the sense of deep respect, reverence and even trepidation, but does not denote fear in the sense that would result in flight from God.

Exodus 24 becomes problematic if we attempt to read it as a simple, coherent sequence. Yahweh commands Moses and company to “come up” the mountain (Exod 24:1), but instead he comes to the people to read “the Book of the Covenant” (Exod 24:3, 7). Afterwards, Moses and company finally go up as originally instructed (Exod 24:9). But strangely Yahweh commands Moses a second time to come up the mountain (Exod 24:12), which he then does (Exod 24:13, 15). A third time Yahweh calls to Moses—but only after an interval of six days while Yahweh’s cloud/glory covers the mountain (Exod 24:16)—after which Moses went up the mountain (Exod 24:18). As we have seen before, these three episodes of Yahweh’s command and Moses’ ascent are likely clues that this chapter consists of three accounts that were originally separate and independent.

Source Yahweh summons Moses goes up Sinai

J (Exod 24:1-2, 9-11) Exod 24:1 Exod 24:9

E (Exod 24:3-8, 12-15a) Exod 24:12 Exod 24:13, 15

P (Exod 24:15b-18a) Exod 24:16 Exod 24:18

Once we recognize this chapter as an edited composite, it begins to make perfect sense as a stitched panorama.

In one account (Exod 24:3–8, 12–15a, likely E), at the base of the mountain Moses announces, writes, and reads the “Book of the Covenant,” to which the people agree. The covenant is “cut” in a sacrificial ritual where half of the blood is sprinkled against the altar and the other half on the people. Moses then ascends the mountain to receive the stone tablets, which Yahweh himself has written (cf. Exod 31:18; 32:15–16).

In a second account (Exod 24:1–2, 9–11, likely J), Moses, Aaron, his two sons, and seventy of Israel’s elders ascend part way up the mountain, where “they beheld God, and ate and drank.” What is described of God, however, is simply the semitransparent platform under his feet.

In a third account (Exod 24:15b–18a, likely P), God manifests his presence visibly in the cloud of his glory (mentioned exclusively in Priestly texts, Exod 16:7, 10; 40:34–35; Num 17:7) with special attention to the seventh day (i.e., Sabbath). In this story line Moses ascends the mountain to receive, not a law code or covenant, but instructions for constructing the tabernacle, the ark, and the priestly vestments, as found in chapters 25–31.

Each narrative strand makes its own thematic contribution to the surprise that is gifted to the Israelites.

Yahweh has uniquely cut a covenant with them—complete with full documentation, including a book and two stone tablets written by God (E).

Yahweh invites Israel’s representatives to have the privilege of a direct encounter and communal meal with the God of Israel (J).

Yahweh’s manifest glory will continue, well beyond this Sinai moment, to attend them in a portable tabernacle (P, cf. Exod 29:43; Lev 9:6, 23; Num 14:10; 16:19; 20:6).

The final redaction of the three combined narratives presents a fuller, complementary panorama of the sacraments that Israel uniquely enjoys.

► The "golden calf" incident exemplifies how Yahweh engages with people.

Exodus 32–34. Old Testament narrative should be read as “torah,” that is, “instruction.” It is not mere history; we are invited to look through these narrative windows to see how Yahweh deals with his people, and so learn what we may expect from him and how we should respond in similar situations.

The problem is that most of us reading the Golden calf story in Exodus 32 regard the Israelites as quite silly, to say the least. They have participated in a whole series of “signs and wonders”—the ten plagues in Egypt, the drowning of the Egyptian army in the Red Sea, and the awesome divine display on Mt. Sinai. Yet after a mere forty-day absence of their leader, Moses, “they made for themselves a molten calf and bowed down to it and offered sacrifices to it” (Exod 32:8). Where did this bizarre idea come from? Most of us feel, “I would have had the common sense to remain true to Yahweh,” and so we identify with Moses and Joshua (certainly not Aaron!). But in so doing, we actually miss important instruction that God has for us. Embedded in our reading are misleading assumptions and a failure to look more closely at context.

First, we need to engage in a close reading of the text itself. At the outset, a key issue is that of leadership, namely “who has led us and who will lead us?” While the overall portrayal within the book of Exodus is clear that Yahweh, by the hand of his agent Moses, is their leader, the perspectives of the various characters within this narrative differ. The Israelites believe it is “Moses, the man who brought us up from the land of Egypt,” and so because of his prolonged absence they demand Aaron to “make for us gods who will go before us” (Exod 32:1, 23, cf. 4, 8). Within the lively dialogue between Yahweh and Moses, Yahweh—for the sake of argument—rhetorically agrees that it was Moses who brought them up from Egypt (Exod 32:7), while Moses retorts that it was Yahweh (Exod 32:11–12).

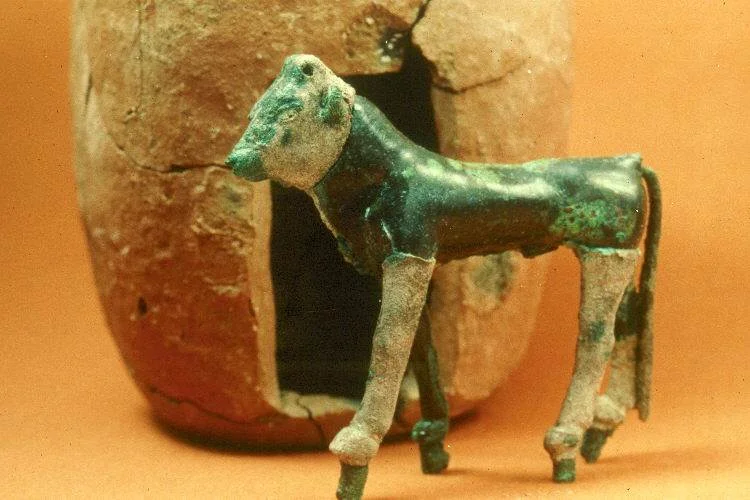

4-inch Silver Calf (ca. 1550, MB, Ashkelon)

► The "young bull" functioned either as an idol symbolizing El/God or a pedestal on which God stood invisibly.

Second, we need to explore the cultural and traditional contexts of the passage. Simply put, the Israelites sought to use a symbol that was popular in the ancient Near Eastern cultures and even shared some endorsement within Israelite faith. The Hebrew word translated “calf” (עֵגֶל) is more accurately translated “young bull/ox” (HALOT, p. 784). In Egypt, the Mnevis bull of Heliopolis was a manifestation of the god Re and the Apis bull of Memphis a manifestation of the god Ptah. Within the West Semitic culture along the Mediterranean, the deity El is frequently named “Bull El,” as seen in the Ugaritic texts. In the Old Testament itself, the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob/Israel shared this name “El,” though not self-evident to most English readers because the Hebrew word is rendered generically as “God” in most translations. Notable examples are the naming of the patriarch, and later the people, as “Isra-El” (Gen 32:28, 30) and Jacob’s altar dedicated to “El (is) the God of Israel” (Gen 33:20), along with the titles “El Most High” (Gen 14:18–22) and “El Almighty” (Gen 17:1; 28:3, etc.). In the ancient poem, the “Blessing of Jacob,” beside the titles “El of your father” and “Almighty” is that of “the Bull of Jacob” (Gen 49:24–25). This may sound strange because most English translations render this title as “Mighty One of Jacob.” But “bull” (Isa 34:7; Pss 22:12; 50:13; 68:30) or “stallion” (Judg 5:22, etc.) appear to be the basic, original senses of this Semitic word (אָבִיר, Ugaritic ibr, see HALOT, p. 6), while “mighty” appears to be its later derived, figurative sense. In the prophetic oracles of Balaam, “El who brings them forth from Egypt” is likened to a “wild ox/bull” (Num 23:22; 24:8, רְאֵם, which is used in parallel to עֵגֶל in Ps 29:6). While not an authoritative biblical text, Samaria ostracon 41 (a tax receipt written on a potsherd) records the name Egel-Yav (עגליו), “a bull calf of/is Yahweh.”

Storm-god from Arslan Tash (Syria)

A second observation from this symbol’s cultural and traditional context is that, while in some cases the young bull may be symbolic of a deity, in others the bull was simply the pedestal on which the deity, usually the weather/storm god, stood (see, e.g., ANEP, figures 500, 501, 531, 534, 537). An example close to Israel was found in Canaanite Hazor (decapitated perhaps by the invading Israelites!). In this light, one thinks of a comparable symbol of God’s presence within orthodox Yahwism, namely the cherubim, on whom Yahweh sits invisibly enthroned (e.g., 1 Sam 4:4; 2 Sam 6:2; Pss 80:1; 99:1). Cherubim are hybrid creatures, typically in the ancient Near East consisting of a human head, eagle wings, lion forelegs, and bull hind legs. They symbolize respectively wisdom, mobility, strength, and fertility. Ezekiel’s vision (Ezek 1:4–28, further interpreted in Ezek 10:1–22) confirms this symbolism was current within Israel. The “living creatures” (Ezek 1:5) or “cherubim” (Ezek 10:1) are a composite of human, lion, eagle (with wings), and ox/bull (with the hoof of a calf, עֵגֶל).

Procession of gods appearing before an Assyrian king (Maltaya)

When the northern tribes of Israel secede from the Davidic monarchy in Judah and Jerusalem, Jeroboam sets up alternative sanctuaries in Bethel and Dan. In language that clearly echoes Exodus 32:4, 8, he “made two calves of gold,” likely to compete with the cherubim throne in the Jerusalem temple (see 1 Kings 12:26–29).

Our contextual explorations have shown that (a) this young bull symbol, contrary to Aaron’s extravagant excuse (“I cast it into the fire and out came this young bull,” Exod 32:24), has some history and validity within Israel’s ancient traditions and that (b) it may have simply represented the pedestal on which Yahweh stood invisibly. If so, what makes the cherubim-throne symbol legitimate and the young bull pedestal in Exodus 32 deserving of such harsh judgment?

► What is wrong with an idol?

Answering the questions, “what constitutes an ‘idol’” and “what is wrong with idolatry?,” would be an article in itself. Here are a few points to consider. First, much depends on the perception of the worshipers. There is a huge step when one moves from imaginative metaphor to tangible symbol. While a visual representation can be powerful and speak a thousand words, its interpretation can be ambiguous. It increases the likelihood of closer identification between deity and object. One may construe that the deity is now obliged to, indeed to some extent even dependent on, the humans who manufactured it. The object may be regarded as a localized medium channeling the deity’s presence, though the same may be said of the legitimate symbols the cherubim-ark and the temple. An image may also foster the rites of divination and incantation which seek to manipulate the deity, as evident in Mesopotamia. What religious officials may intend and what popular opinion perceives may be widely different. The Exodus 32 narrative seems to indicate that while Aaron proclaims the bull calf as emblematic of Yahweh (a violation of the Second Commandment, Exod 20:4), the people perceive it as emblematic of “gods” (a violation of the First Commandment, Exod 20:3). Second, the Bible shows a decided preference for human comparisons with God (e.g., king, judge, shepherd, father, husband, savior, redeemer, warrior) over animal comparisons (e.g., the explicit similes in Deut 32:11–12 and Hos 11:10; 13:7–8). Moreover, cherubim, while sharing in bull imagery, are clearly hybrid creatures and cannot be confused with anything of this world, thus pointing to otherworldly realities. Third, the symbols associated with Yahweh in the Bible are never of Yahweh himself, but are associated with his intangible presence: most notably, the cherubim symbolizing God’s throne and the temple symbolizing his house. Even here, the nature of God’s presence at the temple is variously qualified as his face, his name (in Deuteronomistic texts), and his glory (in priestly texts). According to Jeremiah, the ark is ultimately regarded as dispensable (Jer 3:16–17), as is the temple, with the phrase “this is the temple of the Lord” regarded as “deceptive words” (Jer 7:4, 12–14)! There are other cases in the Bible where symbols once considered legitimate, such as a “standing stone” (Gen 28:18–22; 35:14) and a “bronze serpent” (Num 21:8–9), can become illegitimate, likely because of pagan associations (Exod 23:24; Deut 16:22; Mic 5:13; and 2 Kgs 18:4).

The bottom line: whatever metaphors or symbols people use for God, they must be held lightly. While God accommodates himself to human understanding and discloses himself through metaphors and symbols, the freedom of God cannot be compromised. One generation’s symbol can become the next generation’s idol. Spiritual discernment is ever essential.

Info Box 8.3: The Golden Calf Incident and Ourselves

The issue of Exodus 32 is one of leadership: who leads us? Is it Yahweh, Moses, or a symbol of divine presence? Ultimately it is Yahweh, yes, but even by his own admission Moses is his tangible agent. In his absence, the people invoke a symbol to lead them. This discussion is in no way intended to excuse the Israelites, but it is meant to help us see that they, while they may be silly, are not so far from ourselves. Are we, like the Israelites, so fixed on our human leaders, such as a pastor or theologian, that they eclipse the God they serve? When we feel our God or beloved spiritual leader is absent, on what symbols does our God stand? Is there some symbol—whether it be a church, creed, sacrament, theology, ideology, or flag—that we clutch so tightly that it obscures our view of the living God who will never be boxed in? So the next time we think the Israelites (or the disciples in the Gospels) are a bit silly, we need to look more closely at them—and at ourselves—and we may discover our story in their story and so receive God’s torah/instruction.

► During Moses' intercession Yahweh engages in repartee and favorably accedes to his tenacious negotiations.

Once God observes his people worshiping at the golden calf on Mt. Sinai, thus violating the first two of the Ten Commandments, he gives Moses a clear command: “Let me alone so my wrath may burn against them” (Exod 32:10). Moses refuses! He argues with God on three points:

a) Why would you destroy your investment (Exod 32:11)?

b) Why would you jeopardize your reputation (Exod 32:12)?

c) Remember that you promised Abraham’s descendants possession of the land (Exod 32:13).

The narrator then matter-of-factly discloses the response: “Yahweh relented over the calamity that he said he would do to his people.”

The unfolding narrative is clear: if Moses does not challenge God, the people are “finished” (Exod 32:10, 12). Readers are often troubled by this characterization of God as one who “changes his mind” (an inappropriate translation, by the way, as it might suggest a divine “Oops!”). It appears to violate God’s sovereignty. While the notion of divine sovereignty is indeed biblical, we must also acknowledge its biblical counterpoint, namely divine condescension. Simply put, God voluntarily acts responsively to Moses’ initiative. Later in their dialogue, God says as much when he simultaneously affirms his character of mercy while also declaring his own independence to make such decisions: “I will be gracious with whom I will be gracious and I will have compassion on whom I will have compassion” (Exod 33:19).

Readers often fault the Israelites for identifying Moses, not Yahweh, as the one “who brought us up from the land of Egypt” (Exod 32:1). Yet curiously Yahweh initially agrees with them (Exod 32:7)! Could it be that throughout this dialogue God “teases” Moses? They banter back and forth as to whose people these are and who brought them up from the land of Egypt. To Moses Yahweh calls them “your people, whom you brought up from the land of Egypt” and “this people” (Exod 32:7, 9). Moses counters, identifying them as, “your people, whom you brought up from the land of Egypt” and as “your people” (Exod 32:11–12). Later, Yahweh insists on calling them “the people whom you brought up from the land of Egypt” (Exod 33:1). Moses replies, “you say to me … this people … but consider that this nation is your people” (Exod 33:12–13).

Not only is there repartee in this dialogue, there is tenacious negotiation on Moses’ part. Yahweh’s initial concessions to Moses’ first two intercessions (Exod 32:11–13, 30–32) are to spare the people and to bring them to the land (Exod 32:34–33:5)—exactly as Moses had petitioned, ensuring that Abraham’s multiplied offspring would inherit the land (Exod 32:13). But Yahweh refuses to go up with them himself and so commissions “an angel” instead. As wonderful as these promises are, Moses is not satisfied. One vital element is missing. It is here that the narrator interrupts the dialogue for a parenthesis on “the tent of meeting” where “Yahweh would speak to Moses face to face, as a person would speak to his friend” (Exod 33:11). After Moses petitions Yahweh to reinstate the people, Yahweh replies, “My face shall go, and I will give you (singular) rest” (Exod 33:14, literal; contrary to English translations, there is no “with you”). Moses is listening very closely: Yahweh has yet to promise to go with the people and give them rest. Moses then presses the point that the people’s sole distinctive “from every other people” is Yahweh’s very “face” going with them.

At last, Yahweh says, “This matter about which you have spoken I will do because you have found favor in my eyes and I know you by name” (Exod 33:17). We may have read this passage dozens of times without hearing its full import. Yahweh heeds Moses’ intercession, not because of his compelling legal arguments based on covenant, nor because of his piety or religious respectability, but simply because he likes him and knows him personally!

Info Box: Moses’ Chutzpah

Yahweh enjoys Moses’ initiative and resolute advocacy, for which there is no better word than chutzpah. Moses is neither acquiescent or fatalistic, conceding “well, it must be God’s will.” As at the burning bush (Exod 3:1–4:12), Moses’ persistent questions and petitions prompt some of the most significant revelations from God in the Bible (see further 33:18–34:10). We might think, “hey, I’m no Moses.” True that may be, but Paul believes that the people of the New Covenant have greater access to God’s presence than Moses (see 2 Cor 3:4–18), and thus all the more reason to intercede with chutzpah.

► At Moses' request Yahweh reveals his name in a theophany as both compassionate and uncompromising.

Recognizing the intimacy of their relationship, Moses makes an extraordinary request: “Please, show me your glory” (Exod 33:18). Yahweh promises a second divine appearance (theophany), but this time Moses will have a private audience with God. The narrator (likely J) portrays Yahweh’s presence as localized spatially, thus heightening the intimacy of their meeting: “There is a place by me, and you shall stand upon the rock,” so later Yahweh “stood with him there” and then “passed by” (Exod 33:19–22; 34:5–6). Yet, although still using anthropomorphic terms to describe God’s presence, the distinction between God and humans is clearly maintained: “you are not able to see my face, for man cannot see me and live…. I will cover you with my hand until I passed by. And I will remove my hand and you shall see my back.” While this theophany certainly has visual elements, the focus lies in verbal proclamation, in particular the proclamation of Yahweh’s name (Exod 33:19; 34:5–6). While Yahweh had earlier disclosed his name and its significance to Moses at the burning bush (Exod 3:13–15, E) and in Egypt (Exod 6:2–8, P), he does so again here (J). The first two proclamations were done in the context of socio-economic oppression in Egypt, where the significance of the name Yahweh was attached to liberation. But this time it occurs in the context of rebellion against Yahweh’s commands, where the name is attached to grace. As names, and especially divine names, were revealers of the name bearer’s identity and defining characteristics, modern readers should take special note of these momentous moments when God discloses his Name. Yahweh is fundamentally a liberator—in the face of oppression—and compassionate—in the face of transgression. Although Yahweh’s declaration may sound redundant, “I am gracious with whom I am gracious, and I am compassionate with whom I am compassionate,” it is Yahweh’s declaration of independence, where he avers his sovereign and personal choice. One could paraphrase it as, “I am, in fact, gracious with whom I choose to be gracious.” In other words, as persuasive as Moses’ intercession has been, the decision to show grace to the idol worshipers is entirely Yahweh’s.

Yahweh’s proclamation of his name invites comparison with his earlier elaboration of the second of the Ten Words/Commandments.

Exod 20:5–6

• a jealous God (אֵל, El)

• visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children, showing loyalty to thousands

• Qualifiers: to those who hate me, to those who love me and keep my commandments

Exod 34:6–7

• a compassionate and gracious God (אֵל, El), slow of anger, and great of loyalty and fidelity (“jealous God” is transposed to Exod 34:14)

• Reversal: showing loyalty, visiting iniquity

• No qualifiers

• Addition: lifting iniquity, transgression, and sin (though contrast Exod 23:21)

• Addition: he will not acquit/leave unpunished

As part of Yahweh’s covenant with Israel, the second commandment focuses on their exclusive relationship and on the threat of punishment. In context of the Golden Calf rebellion, this new proclamation of Yahweh’s name focuses on his compassion, patience, and loyalty. It also adds the new possibility of forgiveness, while also maintaining the threat of punishment for those who continue in their transgression. Not surprisingly, Exodus 34:6–7 is one of the most frequently cited passages in the Old Testament (Num 14:18; Neh 9:17; Pss 86:15; 103:8; 145:8; Joel 2:13; Jonah 4:2; Nah 1:3).

Moses has been listening closely: he petitions Yahweh to do as he had just promised, namely to “forgive our iniquity and our sin.” And, as Yahweh has yet to explicitly restore his presence among the people, Moses presses him, “Lord, let the Lord please go in our midst.” Yahweh’s response is to “cut a covenant”—a new one subsequent to the one cut in Exodus 24:8. This passage serves to illustrate the nature of covenants in the Old Testament, whether they be with human parties or with God: these covenants/treaties/contracts are by nature conditional. The covenant itself does not guarantee God’s promises unconditionally. But what ensures the preservation of the divine-human relationship is the God who transcends covenantal obligations—and in this case Moses’ tenacious intercession.

► At Sinai Yahweh delivers the "Ten Words" ("You shall [not]") and the case laws of "the Book of the Covenant" ("If ... then").

Laws (Exod 20–23, 34). In the narrative describing the Israelites’ arrival at Mount Sinai Yahweh had forewarned that he would make a “covenant” with them and that he himself would appear in a theophany, coming in a “cloud” (Exod 19:5, 9). This would be a personal meeting (“I bore you on eagles’ wings and brought you to myself”) and initiate a special relationship (“you will be to me a treasure among all the peoples”). In this respect, the laws that follow reflect Yahweh’s values for the society of God’s people. These are not universal principles for all humanity, but are intended as a particular gift to the people of God. Then, “there was thunder and lightning and a heavy cloud upon the mountain …, so all the people in the camp trembled” (Exod 19:16; cf. 19). The Hebrew word translated “thunder” (qolot) usually means “sound” or “voice” in the OT, so here the thunder is an expression of God’s voice, but suddenly in Exodus 20:1 God’s voice becomes an articulate voice in the delivery of the Ten Words: “And God spoke all these words.”

The material in Exodus 20–23 formally consists of “words” (Exod 20:1) and “judgments” (Exod 21:1; see Exod 24:3 for both). The “words” are phrased as brief statements (“You shall [not] …”), which scholars call apodictic laws. The “judgments” are phrased as conditional sentences “(“If …, then …”), which scholars call case laws. The former present law in principle, and the latter in practice. Only some of the apodictic laws find elaboration in the case laws: worshiping other gods, honoring parents, murder, theft, and perjury (see details in Info Box 8.5 below).

Moses with the Tablets of the Law (Rembrandt). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ARembrandt_Harmensz._van_Rijn_079.jpg

The Ten Words

► The lawgiver introduces himself as liberator and establishes the parameters of how the Israelites are to respect their God and each other.

The Ten Commandments form one of the best-known biblical passages in Western culture. The phrase, “the Ten Commandments,” occurs three times in most English translations (Exod 34:28; Deut 4:13; 10:4), but each time the Hebrew phrasing is literally “the Ten Words.” In the narrative frame we are told, “and God spoke all these words” (Exod 20:1; cf. 24:3). They are not presented as commands, but rather as words of instruction. Exodus 24:12 comes the closest where the stone tablets are identified as “instruction/law (torah) and commandment,” but even here Yahweh has explicitly written them “for their instruction (horot, the same Hebrew root underlying torah).” Most importantly, in the preface to the Ten Words Yahweh identifies himself: “I am Yahweh your God who brought you forth from the land of Egypt from the house of slaves” (Exod 20:2). In other words, he is a liberator, implying these words/commandments are intended to help maintain their liberation, not put them in bondage to law. Perhaps obvious but often overlooked is the clear narrative sequence: the story of liberation and salvation from Egyptian slavery precedes the giving of the law. It is not the Israelites’ obedience to the law that makes them the people of God; they are that already.

Info Box: The Ten Words

How should we count the Ten Words? The Christian tradition separates the prohibitions of worshiping other gods and idolatry, thus counting them 1 and 2. But the Jewish tradition counts the so-called preface (Exod 20:2) as the first Word and combines the prohibitions against other gods and idolatry as the second Word. The Jewish tradition actually has grammar on its side. The pronoun “them” makes no sense in an independent Word prohibiting idolatry (Exod 20:4–6). Otherwise, we should expect “it,” referring to the singular “image/idol.” “Them” can only refer to the “gods” of Exodus 20:3. In addition, the rationale for the prohibition lies in Yahweh as “a jealous God,” who would be jealous of other gods, not idols. Elsewhere the Old Testament sees little distinction between worshiping idols and worshiping other gods. Nonetheless, the following exposition follows the Christian tradition.

1 Exodus 20:3 (lit. “There shall not be for you other gods above my face”), as phrased, instructs Israel how to arrange ("for you" or "you shall not have") Yahweh's place of worship. Israel is forbidden to install other deities at Yahweh’s place of worship. The Hebrew preposition (ʿal), which most English Bibles render as "before," literally means "above/upon." Using the metaphor of a royal court, these would-be deities are forbidden to stand before a seated/enthroned Yahweh. Strictly speaking, this word of instruction institutes monolatry, not monotheism. Monotheism is the belief in one God. Monolatry is the worship of one God without explicitly denying the existence of other deities. The Book of the Covenant likewise prohibits the worship of other gods (Exod 22:20; cf. 23:24, 33).

2 Exodus 20:4–6 supplements the previous prohibition by banning the manufacture of idols or cult statues. Although the Old Testament frequently prohibits idolatry, it rarely provides a rationale. The closest explanation appears in the laws about altars at the beginning of the Book of the Covenant. In Exodus 20:22–26 it might seem strange that Yahweh should use a verb of “seeing” when referring to his act of “speaking” with them “from the skies/heavens.” But his word choice makes sense in light of the following prohibition: “You shall not make with me gods of silver, and gods of gold you shall not make for yourselves.” The Israelites saw nothing of Yahweh, so an image of him is impossible. Yahweh remains transcendent in the skies above and is therefore intangible and invisible to human sight. His presence and his voice are not mediated through earthly objects of human manufacture. The closest Israel can get to sacred objects are altars, yet here there is an explicit departure from ANE culture: instead of precious metals, they may use only common dirt or stones, and even here the stones must not be “profaned” with the use of human tools. The basis for this prohibition lies in Yahweh's character: "for I, Yahweh your God, am a jealous God." Although his jealousy threatens punishment, this divine characteristic presupposes a relationship with his people that is devoted, as in marriage, and therefore exclusive. Jealousy as a divine quality is unparalleled in the ANE.

3 Exodus 20:7 (lit. “You shall not lift the name of Yahweh your God to worthlessness”) refers not to casual swearing, but to invoking God’s name formally, especially in oaths (e.g., “As Yahweh lives, …”; cf. Jer 34:15-16, where covenant violation amounts to "profaning God's name"). It entails not using God’s name to add weight to one’s claims, especially for manipulative purposes, suggesting that God is now party to one’s endeavor.

4 Exodus 20:8–11 enjoins God’s people to “sanctify” the Sabbath day by “not doing any work,” as a reflection of Yahweh’s “resting” on the seventh day after creation. The Book of the Covenant uses the verb form of the noun Sabbath: “on the seventh day you shall cease (šbt)” (Exod 23:12). The elaboration of this Word specifically names the subordinates that the head of the household or business might abuse: children, servants, livestock, and the sojourner.

5 Exodus 20:12 instructs children to “honor” (lit. “give weight to”) both parents, father and mother. Its elaboration is explained by the threats stipulated in the Book of the Covenant (Exod 21:15, 17).

6 Exodus 20:13 prohibits murder and manslaughter, but not killing as a form of capital punishment or in battle. The Book of the Covenant stipulates the death penalty (Exod 21:12–14).

7 Exodus 20:14 prohibits adultery, but the book of Exodus provides no further clarification or elaboration.

8 Exodus 20:15 prohibits theft. The Book of the Covenant stipulates restitution as a penalty for theft of property, whereby the thief must restore to the victim several times over whatever he/she stole (Exod 22:1–4). Theft of a human, or kidnapping, is a capital offense (Exod 21:16).

9 Exodus 20:16 forbids perjury. The Book of the Covenant elaborates, but specifies no penalties. The stipulations are not case laws, but “You shall not …” (Exod 23:1–2).

10 Exodus 20:17 forbids “coveting” a neighbor’s property, which appears to be more a principle of law, rather than one that is enforceable, as it denotes an attitude that may not be manifest in action.

Info Box: The Book of the Covenant (Exod 20:22–23:33) and the Code of Hammurabi

Law Code of Hammurabi (Wikimedia Commons)

Hammurabi was king of Babylon in the 18th century BCE (1792–1750). The main exemplar of his famous law code is on a 7.4 foot stele. Copies were installed in major cities, and the some 50 manuscripts, from Hammurabi’s time to the mid-1st millennium BCE, indicate that it was regarded as a standard of law. It was not the oldest code, but predated by the Sumerian Laws of Ur-Nammu and of Lipit-Ishtar and the Akkadian Laws of Eshnunna.

Compare and contrast the laws from the Book of the Covenant (Exod 20:22–23:33) and the Code of Hammurabi. What similarities and dissimilarities do you observe? What do you think might be the nature of their relationship (e.g., borrowing, independent sources, common cultural tradition)? What do these comparisons suggest about the nature of biblical revelation and inspiration?

Debt Slavery

• When you buy a male Hebrew slave, he shall serve six years, but in the seventh he shall go out a free person, without debt. … If his master gives him a wife and she bears him sons or daughters, the wife and her children shall be her master’s and he shall go out alone. … When a man sells his daughter as a slave, she shall not go out as the male slaves do (Exod 21:2–7, NRSV).

• If an obligation is outstanding against a man and he sells or gives into debt service his wife, his son, or his daughter, they shall perform service in the house of their buyer or of the one who holds them in debt service for three years; their release shall be secured in the fourth year (CH 117).

Striking a parent

• Whoever strikes father or mother shall be put to death (Exod 21:15, NRSV).

• If a child should strike his father, they shall cut off his hand (CH 195).

Kidnapping

• Whoever kidnaps a person, whether that person has been sold or is still held in possession, shall be put to death. (Ex 21:16, NRSV)

• If a man should kidnap the young child of another man, he shall be killed (CH 14).

Injury from a quarrel

• When individuals quarrel and one strikes the other with a stone or fist so that the injured party, though not dead, is confined to bed, but recovers and walks around outside with the help of a staff, then the assailant shall be free of liability, except to pay for the loss of time, and to arrange for full recovery. When a slaveowner strikes a male or female slave with a rod and the slave dies immediately, the owner shall be punished. But if the slave survives a day or two, there is no punishment; for the slave is the owner’s property (Exod 21:18–21, NRSV).

• If an awīlu should strike another awīlu during a brawl and inflict upon him a wound, that awīlu shall swear, “I did not strike intentionally,” and he shall satisfy the physician (i.e., pay his fees) (CH 206).

Miscarriage

• When people who are fighting injure a pregnant woman so that there is a miscarriage, and yet no further harm follows, the one responsible shall be fined what the woman’s husband demands, paying as much as the judges determine. If any harm follows, then you shall give life for life … (Exod 21:22–23, NRSV).

• If an awīlu strikes a woman of the awīlu-class and thereby causes her to miscarry her fetus, he shall weigh and deliver 10 shekels of silver for her fetus. If that woman should die, they shall kill his daughter. If he should cause a woman of the commoner-class to miscarry her fetus by the beating, he shall weigh and deliver 5 shekels of silver. If that woman should die, he shall weigh and deliver 30 shekels of silver (CH 209–212).

Lex talionis (law of retaliation)

• If any harm follows, then you shall give life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, burn for burn, wound for wound, stripe for stripe. When a slaveowner strikes the eye of a male or female slave, destroying it, the owner shall let the slave go, a free person, to compensate for the eye. If the owner knocks out a tooth of a male or female slave, the slave shall be let go, a free person, to compensate for the tooth (Exod 21:23–27, NRSV).

• If an awīlu should blind the eye of another awīlu, they shall blind his eye…. If he should blind the eye of an awīlu’s slave or break the bone of an awīlu’s slave, he shall weigh and deliver one-half of his value (in silver). If an awīlu should knock out the tooth of another awīlu of his own rank, they shall knock out his tooth (CH 196, 199–200).

Goring ox

• When an ox gores a man or a woman to death, the ox shall be stoned, and its flesh shall not be eaten; but the owner of the ox shall not be liable. If the ox has been accustomed to gore in the past, and its owner has been warned but has not restrained it, and it kills a man or a woman, the ox shall be stoned, and its owner also shall be put to death. If a ransom is imposed on the owner, then the owner shall pay whatever is imposed for the redemption of the victim’s life. If it gores a boy or a girl, the owner shall be dealt with according to this same rule. If the ox gores a male or female slave, the owner shall pay to the slaveowner thirty shekels of silver, and the ox shall be stoned (Exod 21:28–32, NRSV).

• If an ox gores to death a man while it is passing through the streets, that case has no basis for a claim. If a man’s ox is a known gorer, and the authorities of his city quarter notify him that it is a known gorer, but he does not blunt (?) its horns or control his ox, and that ox gores to death a member of the awīlu-class, he (the owner) shall give 30 shekels of silver. If it is a man’s slave (who is fatally gored), he shall give 20 shekels of silver (CH 250–252).

Theft

• When someone steals an ox or a sheep, and slaughters it or sells it, the thief shall pay five oxen for an ox, and four sheep for a sheep. The thief shall make restitution, but if unable to do so, shall be sold for the theft. … When the animal, whether ox or donkey or sheep, is found alive in the thief’s possession, the thief shall pay double (Exod 22:1–4, NRSV).

• If a man steals an ox, a sheep, a donkey, a pig, or a boat — if it belongs either to the god or to the palace, he shall give thirtyfold; if it belongs to a commoner, he shall replace it tenfold; if the thief does not have anything to give, he shall be killed (CH 8).

Other shared topics are death by striking and the safekeeping and rental of animals.

Detail of Hammurabi before Shamash, the sun god and god of justice (Wikimedia Commons)

► Following the laws that parallel the Code of Hammurabi are laws that are shaped by Israel's experience in Egypt and their theology of Yahweh and that forbid abuses of the disadvantaged.

The bulk of the parallels between the Book of the Covenant and ancient Near Eastern law codes occur in Exod 21:2–22:19. Thereafter the laws become more peculiarly Israelite, as evidenced in the next verse which prohibits sacrificing to any deity aside from Yahweh (Exod 22:20). Then, the repeated injunctions, “a sojourner you shall not abuse, nor oppress him, for you were sojourners in the land of Egypt” (Exod 22:21; 23:9), serve as bookends to laws that safeguard those marginalized in society who would be unable to defend themselves legally: the sojourner, the widow and orphan, the poor, and even the wandering ox belonging to one’s enemy. It is noteworthy that Israel’s own experience of abuse informed their law code to ensure that future generations of Israelites would not abuse the helpless in their own society. In addition, these laws were informed by their theology of Yahweh. This section is also marked by explicit theological comments on Yahweh’s character of compassion and readiness to hear the cries of the oppressed and to execute justice on their behalf. It was not customary in other ancient Near Eastern societies that the behavior of the gods would serve as a model for humans to emulate.

The remainder of the Book of the Covenant consists of two distinct bodies of material: a liturgical calendar (Exod 23:10–19) and—in anticipation of Yahweh’s driving out the Canaanites—a prohibition against forming a “covenant” with the Canaanites, which would lead to serving their gods (Exod 23:20–33). Israel’s covenant would be exclusively to Yahweh, as formalized in the following chapter. As a requisite part of any ancient Near Eastern covenant/treaty was invoking the gods of both states to serve as witnesses of the contract, cutting a covenant “with them” entails cutting a covenant “with their gods” and “invoking the names of other gods” (Exod 23:13, 32). The sole action that the Israelites are to take against them here is to “tear down” their gods/idols and to “shatter their standing stones” (Exod 23:24). No action is prescribed against the Canaanites themselves—unlike the book of Deuteronomy, which commands the "ban" of destruction.

► A liturgical calendar lists the three pilgrim festivals, identified by their agricultural names.

The Pentateuch contains five liturgical calendars (Exod 23:10–19, E; 34:10–27, J; Deut 16: 1–17, D; Num 28:1–29:40, P; Lev 23:1–44, H), but the two embedded in the book of Exodus are likely the oldest. The calendar in the Book of the Covenant begins with the sabbatical year, when the land is to lie fallow, for the benefit of the poor and the “creatures of the field” (usually wild animals). The sabbatical day, the seventh, allows working animals, servants, and sojourners to “take a breather” (literally). It is noteworthy that the stated reasons are not religious, theological, nor essential to Israelite identity, but are social and ecological.

The annual calendar is marked by the three pilgrimage festivals/feasts, consistently referenced in all five liturgical calendars, but they are here identified by their agricultural names–Unleavened Bread (at the time of the barley harvest), Harvest (of wheat), and Ingathering (of fruit and olives)—not by their more familiar names of Passover, Weeks and Tabernacles. The first feast is linked with their departure from Egypt, but the second two with “sowing” and “gathering” from “the field.” Attendance is required by the “males,” presumably ensuring that the women and children are there to manage the farm and the herd back home. Although feasts are clearly a time of celebration, this short passage emphasizes they are to be observed “to me,” such that all worshipers are to “appear before me” (twice). The latter phrase is problematic in Hebrew: “they shall not appear my face” (literally). Lacking is the expected preposition “before” in Exodus 23:15. (Exod 23:17 is also problematic, though more complicated to explain.) The textual problem can be resolved with the hypothesis that the original Hebrew vowel points read, to “see my face,” but were altered later by well-meaning scribes who are troubled by the apparent contradiction that “man cannot see my face and live” (Exod 33:20). Yet, there may be no contradiction once interpreters recognize that Exodus 33:20 occurs in the context of a theophany, that is, a more literal encounter with God’s self-manifestation, while Exodus 23:15, 17 employ the metaphor of the subject/worshiper summoned to have an audience with the divine king at his palace/temple. Consistent with this metaphor is the admonition that the worshiper should not appear “empty-handed,” that is, without a gift of tribute to one’s monarch.

► Because the Israelites broke the Sinai covenant, Yahweh "cuts" with them a second covenant, which includes another edition of a liturgical calendar.

A Second, Parallel Covenant (34:10–28). Parallel to the covenantal material in Exodus 20–24 (E) is another covenant in Exodus 34:10–28 (J). But in the final narrative sequence (once J and E are combined), this second covenant (“I am about to cut a covenant,” Exod 34:10, 27) is necessary because Israel had forfeited the first covenant (Exod 24:7–8) in the Golden Calf incident. (The combination of originally separate sources is evident in Exod 34:28, wherein Moses then “wrote on the tablets the words of the covenant, the Ten Words,” even though one cannot identify ten words or commandments in this passage.) The material in the second covenant is not as extensive and parallels only the last two sections of the Book of the Covenant, namely the prohibition of cutting a covenant with the Canaanites (Exod 23:20–33 // Exod 34:10–17) and the liturgical calendar (Exod 23:10–19 // 34:18–26). While the Book of the Covenant prescribes only the “tearing down” at their gods and “shattering their standing stones”(Exod 23:24), this second covenant adds “cutting down their Asherah poles/trees” and most significantly a prohibition against intermarriage (Exod 34:13, 16). This second covenant reiterates the reminder that cutting a covenant with other peoples would entail “worshiping another god” (Exod 34:14 // Exod 23:24).

This second liturgical calendar lists the same three pilgrimage festivals, but the second is named “Weeks,” instead of “Harvest,” though it does explicitly attach it to the “wheat harvest.” It also adds to the Feast of Unleavened Bread the rite of “redeeming” the firstborn, especially of human sons. The injunction of the sabbatical day is inserted between the first and second festivals.

► Yahweh delivers to Moses the blueprints for the Tabernacle, where Yahweh will reside in the midst of the people.

Tabernacle (Exod 25–31; 35–40). As noted above regarding the narrative of Exod 24, Moses—in the third account of his ascent up Mount Sinai—receives not a law code or covenant, but instructions for constructing the tabernacle, the ark, and the priestly vestments, which are detailed in chapters 25–31. These chapters contain Yahweh’s instructions (“Yahweh spoke to Moses, saying …,” Exod 25:1; 31:1, et al), while chapters 35–40 contain Moses’ relay of those instructions to “all the assembly/congregation of the Israelites” (Exod 35:1, 4) and their execution in the construction of the tabernacle. The second section duplicates much of what is said in the first, but the point is to demonstrate that “all the work of the tabernacle of the tent of meeting was finished and the Israelites did according to all that Yahweh had commanded Moses, thus they did” (Exod 39:32, 42–43; 40:16).