Genesis 12-50

A tomb Painting from Beni Hasan in Egypt (ca. 1890). An inscription reads, “The arriving, bringing eye-paint, which 37 Asiatics brought to him.”

9.1. The God of the Fathers: A God of People

► The God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob is a God of people, not cosmic domains (ANE). In so doing, he risks his reputation.

If we were to ask church leaders, pastors and teachers, “what should be our fundamental beliefs about God?”, many would mention the doctrines of monotheism and sovereignty, along with attributes of love, faithfulness, and righteousness. But if we are correct to see the stories of Abraham as the beginnings of salvation history and of God’s progressive revelation, we are struck by a quite different agenda in God’s curriculum for his people. “I am the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob” (Gen 24:12; 26:24; 28:13; 31:42; Exod 3:6, 15-16) is a statement that this God is fundamentally a God of people—one who identifies himself by associating with people. We are immediately struck by how personal this deity is. Unlike other deities of the ancient Near East, he is not known primarily as a god of nature or of place (as, e.g., Marduk is the storm god and patron deity of Babylon). Instead of associating himself with powerful forces in nature or with a city, he links himself with persons. His primary domain is not natural forces; he is a patron of people. At the beginnings of Yahweh’s saving story he does not enmesh himself with political entities and their armies but with a nomadic family. He will later be known as the God of the storm and as the God of Israel, but his first point of emphasis is that he is the God of Abraham.

Another point we should take to heart from “the God of Abraham” is that if we want to know who this God is, we must know the narratives about Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. In other words, he makes himself known not by theological doctrines, propositions or concepts, but by stories—stories that are entwined with all the particulars of time, location, and culture.

Also striking in this choice of self-designation is God’s condescension: he ties his own reputation to the behavior and welfare of particular individuals. God takes certain risks in doing so. We could well imagine Abraham’s contemporaries not being impressed with him and his patron deity. While Abraham does enjoy a measure of wealth, he obtains it by his own conniving and suffers more domestic disputes than any of us would choose. Were we to ask Pharaoh (Gen 12) or Abimelech, king of the “Philistines” (Gen 20), they would not have been charmed by his “testimony.” Nevertheless, Yahweh continues to remain “the God of Abraham” and remains loyal to him.

► The Hebrew ancestors conceived of their deity as "God of the fathers," who acted as guardian deity of the clan.

Another risk God takes lies in the potential misunderstanding that he is merely a clan deity—among many other patron deities. This risk may not enter the minds of Christian readers because preceding Gen 12 is the primeval history of chapters 1-11, which portray Yahweh as the one and only God. But in the original telling of the story and certainly from the perspective of the characters within the stories themselves, there is no claim that Abraham’s God is the one true God of all. For example, this becomes clear in the encounter between the patriarchs of their respective clans, Laban (Gen 31:29) and Jacob (Gen 31:42). The deity of Jacob's clan is not the deity of Laban's. And while Abraham's servant is on an expedition to find a wife for Isaac, he prays to "the God of my master Abraham" (Gen 24:12). Evidently, God’s first priority in salvation history is to say that he is a God of people—not that he alone is God.

Info Box 9.1: Apparent Polytheism and a Scribal Gloss

Gen 31:53 reads literally, “‘the God of Abraham and the God of Nahor—may they judge between us—the God of their father.’ And Jacob swore by the Fear of his father Isaac.” The odd placement of “the God of their father” in the sentence is probably best explained as a later scribal gloss, which attempts to rationalize the apparent polytheistic belief, as evidenced by the plural verb. This phrase is actually missing in two manuscripts of the Hebrew Masorectic text and in the Septuagint, a Greek translation.

Most readers of the Bible do not take particular interest in personal names and their meanings, but they can be very revealing about their popular beliefs. If we look at the personal names that parents gave their children prior to Moses and his reception of the personal name “Yahweh,” we see God was sometimes conceived as a kinsman or relative of the name bearer. (While most of the following people are contemporary to Moses, their parents named them before he became their leader.) “Eli-ab” means “my God is Father” (Num 1:9). “Ammi-El” means “my kinsman is God” (Num 13:12). “Abi-ram” means “my father is exalted” (Num 16:1), where father denotes “my divine father,” not the human father. We often think that understanding God as our heavenly Father was an innovation from Jesus, but we find this belief already implicit in the early pages of the Old Testament. Jesus, in fact, simply develops this revelation in his own distinctive way. This tradition carries over to Yahwistic names: Abijah (אֲבִיָּה, אֲבִיָּהוּ, אביו in Samaria Ostracon 52).

9.2. God’s Purposes and Mundane Living

► While Abraham is occupied with family life, he seems unaware that he is an agent in God's larger plan of bringing blessing to the nations.

Often we do not stop to consider the literary structure of an entire biblical book or collection of books, but this can be one of the most helpful exercises to shed light on the key points God is making for us readers. A primary purpose of the primeval history in Genesis 1-11 is to state the problem of escalating human sin and divine punishments (as we proceed through the stories of the fall, Cain and Abel, the flood, and the Tower of Babel). The following chapters, and indeed the rest of the Bible, present God’s solution to this stated problem. Genesis 12 is thus the formal beginning of salvation history. Here God moves from nations and newspaper headlines (Genesis 11) to a single, nomadic family (Genesis 12). And so we should ask, does Abraham have any clue that he is the beginning of God’s solution to the crises of the Tower of Babel, the flood, the fall of Adam and Eve, and even the human condition? Hardly! God’s opening promises (Gen 12:1-3) might engender dreams that his descendants will one day form a great nation and that he will have a great reputation, so much so that other people’s will bless themselves by Abraham’s name. But this is a scarcely what actually unfolds and climaxes in his descendant, Jesus of Nazareth. To underscore the surprise this should evoke we may imagine the solutions we might propose to the problem of escalating sin and judgment, perhaps a church committee with an extensive PR campaign along with strategies to place godly Christian leaders in key positions of government. Our plans would be a far cry from God’s hidden and yet profound work. In fact, what preoccupies Abraham is food for his family (which explains why he passes straight through the so-called promised land), rescuing his nephew, having a child and heir, and settling numerous domestic disputes. There is nothing here that is extraordinary (except perhaps the heroics in Genesis 14). We should also observe the time frame of these stories. We have perhaps imagined that life in Bible times was full of miracles and that as we flip the page from one chapter of the Bible to the next we are simply waking up the next morning to hear another conversation between God and his believers. But in fact, between Genesis 12 and 21 there passes 25 years (cf. Gen 12:4 and 21:5). Again, if we imagine we had delegated a committee to solve the problems of Genesis 1-11 and they focused on one family and spent 25 years before delivering on a key promise, how would we evaluate their work? No doubt, we would fire them for lack of effectiveness and efficiency. But God clearly has another agenda, different values and time frames. His actions, or apparent lack thereof, may not be understandable to us, but these observations of the past should help us appreciate the mysteries of our lives in the present. We should be encouraged with the awareness that as we go about our day-to-day, mundane affairs God may be working his divine purposes. We may think we are simply raising children, herding sheep or working in an office, but God may be aware of a work that changes people’s destinies.

We may be so accustomed to the stories Genesis that we find it unremarkable that salvation history begins with the stories of Abraham and his family. But when we consider that when ancient literature began in Egypt and Mesopotamia, their monuments and stories concerned the gods and kings. But Yahweh, on the contrary, first identifies himself as the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob. These human figures are not royalty but chieftains of nomadic clans at best. This deity associates not with the elite alone but with common folk.

9.3. God’s Agents and the Nations: The Purpose of Election

► God chooses Abraham's family, not as an end in itself, but as a means of bringing blessing to all the families of the earth.

The belief that one has been chosen by God can fill the believer with comfort and assurance—one is special to God! But this belief, of course, is a matter of perspective. To outsiders it smacks of exclusivism and favoritism. The belief that “we are the chosen” endears some and enrages others. Why should God “choose” anyone—with the implication that he is not chosen others? In theological terms, God’s “choice” has to do with the doctrine of “election.”

The notion of God’s chosen people begins when God first speaks to Abraham. While Genesis 12:1-3 does not actually use the word “choose,” Yahweh obviously separates him from homeland and “kindred.” His descendants he promises to make a distinctive “nation.” Moreover, Yahweh makes Abraham himself the touchstone of whether people will be blessed or cursed. While this certainly marks out Abraham as special, it is not an end in itself. This is made clear by the promise’s final clause: “and in you all the families of the earth shall be blessed.”

Info Box 9.2: “Be blessed” or “bless themselves” (Gen 12:3)?

As the marginal note in the NRSV indicates, the clause, “in you all the families of the earth shall be blessed,” could also be translated, “by you all the families of the earth shall bless themselves” (וְנִבְרְכוּ, Niphal). In other words, it is possible that this blessing is not one granted by God (understanding “be blessed” as a theological passive) but one that the families of the earth simply invoke on themselves: “May we be blessed like Abraham has been blessed.”

Here is stated the purpose of God’s election of Abraham. The mention of “all the families of the earth” connects with “the families of Noah’s sons” (Gen 10:5, 18, 20, 31, and esp. Gen 10:32). Evidently, God has chosen Abraham in order to bring blessing to all the human families. This connection is made all the clearer when we observe the thematic links between the Primeval History of Genesis 1-11 and the stories about Abraham and sons in Genesis 12-50. Simply stated, a dominant theme of Genesis 1-11 is the problem of escalating sin and punishments. Genesis 12 begins to narrate God’s solution. The peoples of the earth will obtain God’s blessing through Abraham’s descendants.

The purpose of election has to do with God’s means of bringing salvation to all; it is not God’s end in order to have his favorites and exclude others. When we flip the page from the “Table of Nations” in Genesis 10 and the “Tower of Babel” in Genesis 11 to the story of Abraham in Genesis 12, the stage of the narrative shrinks considerably: from all families and nations to one family! But while the means of salvation narrows, the scope of salvation remains universal. We must not confuse God’s favor with favoritism. Election is not about a pool of God’s blessing but a channel of God’s blessing.

Christians claim ownership to the first three-quarters of their Bible by calling them the “Old Testament.” But even Christians should take their lead from the apostle Paul who identifies the gospel as “the power of God for salvation to everyone who has faith, to the Jew first and also to the Greek” (Rom 1:16, cf. 2:9-10; 3:1ff.). And the Old Testament itself makes a clear claim on the matter: “He declares his word to Jacob, his statutes and ordinances to Israel. He has not dealt thus with any other nation; they do not know his ordinances. Praise the LORD!” (Ps 147:19-20). One scholar has characterized the church’s adoption of Israel’s scriptures as “reading someone else’s mail”—a privilege that Gentile Christians have been granted in the New Testament and a privilege foreshadowed in the Old Testament (Paul van Buren, “On Reading Someone Else’s Mail: The Church and Israel’s Scriptures,” in Die Hebräische Bibel und ihre zweifache Nachgeschichte (FS R. Rendtorff; Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 1990) 595-606; cited in Christopher R. Seitz, Word Without End: The Old Testament as Abiding Theological Witness (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998), see esp. pp. 73, 214).

►Nevertheless, the OT is relatively silent about the nations sharing in God's blessing until Isaiah 40-66, some 1500 years later.

We have seen that God’s choice or “election” of Abraham and his seed/descendants was in direct response to the dire need of “the families of the earth” for God’s blessing Gen (12:1-3 and 10:32). While we might understand Genesis 12:3 as a programmatic statement that God’s ultimate intention is to bless all nations through Abraham’s descendants, we should also note the Old Testament’s relative silence about God’s interests in the Gentiles. Little is said about God’s concern for the nations/Gentiles, surprisingly, until Isaiah 40-66! Even in these chapters foreigners are viewed largely negatively, and if they are to be included in any sense among the people of God, their position is clearly subordinate. But there are expressions in the so-called “Servant Songs” that clearly reach out to the nations: “Here is my servant, whom I uphold, my chosen, in whom my soul delights; I have put my spirit upon him; he will bring forth justice to the nations…. He will not grow faint or be crushed until he has established justice in the earth; and the coastlands wait for his teaching…. I am the LORD, … I have given you as a covenant to the people, a light to the nations” (Isa 42:1). And in the second Servant Song, the servant himself speaks: “Listen to me, O coastlands, pay attention, you peoples from far away! … He [Yahweh] says, “It is too light a thing that you should be my servant to raise up the tribes of Jacob and to restore the survivors of Israel; I will give you as a light to the nations, that my salvation may reach to the end of the earth” (Isa 49:1, 6; see also 52:15). And even outside of the Servant Songs, Yahweh extends a virtual “altar call” to the nations: “Turn to me and be saved, all the ends of the earth! For I am God, and there is no other” (Isa 45:22).

To our surprise the Old Testament is virtually silent about God’s salvation for the nations from Genesis 12 to Isaiah 42. Historically that represents the gap of approximately 1500 years (ca. 2000 BC to ca. 550 BC)! Since most Christians are Gentiles, we should have a great deal of self-interest vested in this issue.

9.4. The “Will of God” and the Promise of Land to Abraham (Gen 11-15)

► Biblical narratives reflect the

complex interplay between

God's will and human decisions,

and between divine sovereignty

and human responsibility.

If we are interested in how God interacts with individuals, the stories about Israel’s ancestors—namely Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and Joseph—are particularly fruitful ground for exploration. Here we find a concentration of incidents where both parties take initiatives and respond to each other. Biblical narratives reflect the complex interplay between God's will and human decisions, and between divine sovereignty and human responsibility.

These narratives are sometimes subtle in the messages they contain. We may have read these stories about Abraham dozens of times without realizing that they give us hints regarding the age-old question concerning the will of God and our role in decision making. An excellent example occurs early in the Bible where Yahweh first promises land to Abram in Genesis 12. As the story unfolds, he reveals his will in stages. He clarifies his promises and directives as Abram encounters new experiences. These clarifications become more understandable once we consider what events have happened since Yahweh’s previous revelation. Yahweh indeed gives the initial directive and ultimately achieves his goal, but this does not preclude human decisions and complications along the way.

We should take note that Yahweh’s initial promise and directive is not very specific: “go (הלך) … to the land that I will show you.” Strictly speaking, Yahweh has not promised to give any land to Abram, only to “show” it to him. Three verses later we are told that Abram “went (הלך) as the Lord had told him,” but where he goes we are not told until the next verse. Here we are informed that “they set forth to go (הלך) to the land of Canaan,” but who specified this direction and destination? The reader may wonder whether this was Abram’s decision or a directive from Yahweh not contained in the story. We should note that even prior to Yahweh’s first words to Abram, Terah—Abram’s father—had decided to move the family from Ur “to go (הלך) into the land of Canaan” (Gen 11:31). This would make the choice of Canaan a third-party decision, involving neither Yahweh nor Abram directly. On the other hand, Yahweh—later—claims, “I am the LORD who brought you out of Ur of the Chaldeans, to give you this land to possess it” (Gen 15:7). So, what may have appeared to be simply a human decision turns out to be divinely instigated. Some decisions may be made by a third party—and still work within God’s will.

However Abram arrived in Canaan, Yahweh reveals his first clarification regarding the promise of land in Gen 12:7: “To your offspring I will give this land.” This promise offers the good news of a land-grant but contains the bad news that Abram himself will not receive it, only his descendants. The narrator has just informed his readers that someone else resides in it: “At that time the Canaanites were in the land.” Nevertheless, Abram’s construction of an altar implies he responds with gratitude in worship.

The extent of this “land” Yahweh does not spell out until his second clarification regarding the promise: “Raise your eyes now, and look from the place where you are, northward and southward and eastward and westward; for all the land that you see I will give to you and to your offspring forever” (Gen 13:14-15). What has happened in the meantime since Yahweh’s last promise regarding the land (Gen 12:7)? Abram’s first experience of the promised land had been that it could not support his family because “there was a famine in the land. So Abram went down to Egypt to reside there as an alien, for the famine was severe in the land” (Gen 12:10). Then after returning to Canaan, Abram and Lot have since learned that “the land could not support both of them living together” (Gen 13:6, and the next verse reminds us that Canaanites and now Perizzites crowd the land). Moreover, Abram has just seen Lot choose “the plain of the Jordan” that “was well watered everywhere like the garden of the Lord” (Gen 13:10). The reader is left to wonder if Abram was getting concerned about the value and extent of his “land.” And so the narrator informs us that it is immediately “after Lot had separated from him” that Yahweh reassures him of his promise and clarifies that Abram’s land extends as far as the eye can see.

This second clarification regarding the land appears to add one more significant piece of information: “all the land that you see I will give to you and to your offspring forever” (repeated in Gen 13:15 and 17; cf. 17:8). For the first time, Abram should understand that not only will he “see” the land, he will also receive it. Later, in a third clarification Yahweh repeats this aspect of the promise in Gen 15:7 and specifies further that he “gives” Abram “this land to possess.” Abram is listening carefully to this new emphasis on possession, so he asks, “how am I to know that I shall possess it?” It is Abram’s question that brings Yahweh to formalize his earlier promises (Gen 12:1-3) in the form of a covenant-contract ceremony (Gen 15:18).

Within this ceremony Yahweh’s fourth clarification about the land is both reassuring and disturbing, as hinted by the “deep and terrifying darkness” that “descended upon him” during his dream-vision (Gen 15:1, 12). First the bad news: “your offspring shall be aliens in a land that is not theirs, and shall be slaves there.” Several generations after Abram will not possess any land at all. As for Abram himself, Yahweh promises only that “you shall go to your ancestors in peace.” Yahweh says nothing specific about Abram’s stake in the land. Apparently, Abram’s share is with his ancestors, not with his descendants in the land! Next the good news: the fourth generation of Abram’s descendants will return to take possession of the land. At this point Yahweh expands the boundaries of Abram’s real estate considerably: “To your descendants I give this land, from the river of Egypt to the great river, the river Euphrates” (Gen 15:18), a distance of roughly 475 miles as the crow flies. Yahweh also spells out that they will possess the land that currently belongs to various peoples (the ten “-ites” listed in Gen 15:19-21). Again, a significant event has transpired in the meantime. Prior to this disclosure Abram has had to lay his life on the line and battle kings to rescue Lot (Gen 14). So Yahweh reassures him that his descendants will secure a place among the peoples and nations. It would seem that Yahweh unfolds his will and promises on a “need-to-know basis.” Yahweh’s earlier promise, “all the land that you see to you will I give it, and/even to your seed forever” (Gen 13:15, literal translation), might sound like Abram himself is to receive the land. But Yahweh later makes it clear that he meant, “to you will I give it, that is, to your seed forever.” In the context of the promise, “the land of Abram” actually means the land that Abram’s progeny will “inherit” (cf. Exod 32:13). As it turns out, Yahweh’s promises may not unfold as the recipient had hoped.

There is another feature of the narrative that illustrates the interplay between Yahweh’s revealed will and Abram’s decision-making. In Gen 12:7, while Abram is at Shechem, Yahweh promises, “To your offspring I will give this land.” One might expect Abram now to settle down, but instead he moves his tent to the south between Bethel and Ai (Gen 12:8). And then, he “journeyed on by stages toward the Negeb” (Gen 12:9). Next, because of famine he travels further south to Egypt (Gen 12:10). After departing Egypt, he journeys through the Negeb to his former tent site between Bethel and Ai (Gen 13:1, 3). Why does Abram keep traveling after Yahweh had just promised him the land around Shechem? It is not until Gen 13:17 that Yahweh explicitly commands Abram, “Rise up, walk (הלך, Hith.) through the length and the breadth of the land, for I will give it to you” (Gen 13:17). Afterwards, he moves his tent near Hebron (Gen 13:18). It would seem that Abram has been doing what Yahweh wanted all along, aside perhaps from the sojourn in Egypt. Apparently, he has been doing God’s will without being aware of it—only to recognize it later.

There are details in this Abrahamic narrative that are very telling about events and their interpretation, especially in terms of the relationship between God’s will and human decision. We live in the midst of a myriad of circumstances; sometimes they arise because of our own decisions, sometimes because of others’ decisions, and sometimes because of coincidence. Who is making the decisions: people or God? Yet the biblical narrative reveals that sometimes Providence is working through such seemingly random events.

► The Bible presents us with both perspectives: the ambiguous present and a retrospective where we see God's hand.

At the beginning of the story the narrator tells us, “Terah took Abram his son … and he brought them out (יצא) from Ur of the Chaldeans to go toward the land of Canaan” (Gen 11:31, my translation). But later Yahweh claims, “I am the LORD who brought you out (יצא) from Ur of the Chaldeans, to give you this land to possess it” (Gen 15:7). These claims are identical (bringing Abram from Ur to the land of Canaan), except for the agent who performed them. What may have appeared to be simply human decision turns out to be divine providence.

Later, when instructing his servant about finding a wife for his son, Abraham adopts Yahweh’s perspective: “Yahweh, the God of the heavens, who took me from my father’s house and from the land of my kindred,” Gen 24:7, my translation; cf. Gen 20:13). It is worth comparing this claim with the narrator’s earlier telling of how events unfolded. Here it was Terah who “took his son Abram … and brought them from Ur of the Chaldeans to go toward the land of Canaan” (Gen 11:31, my translation). Then it was Abram who “took” his family and “set forth (also יצא) to go to the land of Canaan” (Gen 12:5). The beauty of the Bible unfolding the story in this way is that the narrator first tells the story from the perspective contemporary to the events as they unfold. This reflects the present moment in which we live. Only later is it disclosed to Abraham and to us that these events were, in fact, God’s doing. The present moment may seem uncertain, but this uncertainty offers no comment on God’s role: is he actively present or not? Indeed, it may be only in retrospect that we learn that God has been the Director in our script all along. The Bible presents us with both perspectives: the ambiguous present and a retrospective where we see God's hand.

Info Box: 9.3: When did God first speak to Abram?

One might suppose there was another circumstance whereby Abram is taken from his father’s house, namely Terah’s death (Gen 11:32). The apparent sequence in Gen 11:31-12:4 is that after Terah’s death Yahweh first speaks to Abram, and then Abram departs for Canaan. But the (priestly?) narrator evidently expects us to read carefully and do the math from Gen 11:26 (Terah = 70, Abram = 0), Gen 11:32 (Terah = 205, Abram = 135), and Gen 12:4 (Terah = 145, Abram = 75). Apparently Abram departed from Haran 60 years before Terah’s death.

► The bottom line: there are no patterns or formulas when it comes to discerning the will of God, yet he fulfills his promises.

The bottom line is there is no formula when it comes to the will of God: when he reveals it and how much he discloses, and when humans should make decisions and when they should pray. Complications may arise, some traceable to the individual believer, some to a third-party, and some to natural circumstances (e.g., the famine). But in the end, God’s will succeeds. We should find this reassuring. But we should not reduce this narrative to a story of God’s triumph, though it is, because it also gives space, if not more space, to the human drama—with all its complications. As said before, this assures us of God’s ultimate success, but it also assures us that when life seems confusing and overwhelming, such circumstances are typical of the people of God. God would no sooner abandon us, than Abram.

Another curious feature of this narrative is that at no point does Yahweh give Abram any instructions about spirituality. If we look for patterns when Yahweh speaks and when Abram prays, we can find none. These stories provide no patterns or formulas when we should pray or when God should speak, yet he fulfills his promises. When Yahweh gives direction, he “appears” (Gen 12:7) or just “speaks” (Gen 12:1; 13:14) without any prior prompting from Abram. In one case, “the word of the Lord came to Abram” (Gen 15:1), which is a formula familiar to the Prophets. Here it occurs in “a vision” (Gen 15:1) and a dream (Gen 15:12). When Yahweh chooses to speak and when he refrains cannot be correlated with any set of circumstances. On several occasions Abram builds an “altar” and “calls on the name of Yahweh.” In some instances, he does so in response to a revelation from Yahweh (Gen 12:7; 13:18; 22:9; and 15:9-10, 17-18, though there is no explicit mention of an altar). In others, he simply does so on his own initiative (Gen 12:8; 13:4; 21:33). Curiously, in each of these three cases there is no immediate response from Yahweh. The only feature that recurs in these contexts is the mention of a specific geographic site (Shechem, Gen 12:6-7; near Bethel, Gen 12:8; 13:3-4; Hebron, Gen 13:18; Beersheba, Gen 21:33; Moriah, Gen 22:2, 9; cf. 2 Chr 3:1), implying these altars and the like are mentioned because they had made these sites sacred. On the other hand, there are several crises where we would expect Abram to pray or Yahweh to intervene with a promise or directive, but neither do so: when there is famine in Canaan (Gen 12:10), when the ancestral family is threatened in Egypt (Gen 12:10-20), when there is feuding between Abram’s laborers and Lot’s (Gen 13:5-12), when Abram’s nephew chooses to live among the “great sinners” of Sodom (Gen 13:13), when Lot is captured (Gen 14:12), and when the ancestral family is threatened in Gerar (Gen 20:1-18). (For each of these predicaments we can imagine Abram and Sarai setting up a prayer chain!) And there are several moments of good news when we would expect Abram to worship: after receiving Yahweh’s promise of blessing (Gen 12:1-3), and after the ancestral family is miraculously spared in Egypt and later in Gerar (chaps. 12, 20). But in these cases the narrative makes no mention of Abram’s praying or worshipping or of Yahweh’s speaking. And it never faults Abram for making his own decisions, nor for failing to seek God’s will at every step. Yet Yahweh ever remains “the God of Abraham” (Gen 24:12, 27, 42, 48; 26:24, etc.; cf. Gen 17:7). (Ironically, the model for step-by-step prayer and seeking of Yahweh’s directives is Abraham’s servant, who is sent to find a wife for Isaac, as told in the narrative’s longest chapter, chapter 24.) These stories about Abraham resist providing any formulas. While Yahweh's goals are being realized, the narratives focus on the process—in the day-to-day where God's people live.

9.5. The “Will of God” and the Promise of Descendants to Abraham: Complications and Clarifications (Gen 11-15)

► Strangely, Yahweh may reveal his will in parts and so allow his people to make their own decisions, which may lead to complications and consternation.

Valuable insights come to the surface when we do a “close reading” of the same chapters but this time examining Yahweh’s promise of descendants to Abraham. Like the promise of land, the promise of descendants is disclosed gradually. We could make some sense of the gradual unfolding about the land as Yahweh was responding to Abraham’s new experiences and developing circumstances. But in the case of Abram’s descendants, Yahweh’s lack of specificity and clarity opens the door for considerable complications! Strangely, Yahweh may reveal his will in parts and so allow his people to make their own decisions, which may lead totheir consternation.

► (a) God promises Abraham many descendants (Gen 12-13). (b) God informs Abraham that he will be their father (Gen 15). (c) Sarah provides a surrogate (Gen 16). (d) God informs them that Sarah will be their mother (Gen 17 [P]; 18 [J]).

Yahweh’s initial speech to Abram touches on this issue: “I will make of you a great nation” (Gen 12:2). Not only does the promise imply many descendants, it explicitly indicates they will form a significant political entity, one with its own government and territory. In Yahweh’s next speech he makes specific reference to “your offspring” (lit. “seed,” זרע, Gen 12:7), to whom he promises the territory or “land” of Canaan. In his third speech his promise concerns their numbers: “I will make your offspring like the dust of the earth” (Gen 13:16).

Yahweh begins his next dialog: “Do not be afraid, Abram, I am your shield; your reward shall be very great” (or, “I am a shield for you, your very great reward,” Gen 15:1, my translation). Abram’s response is hardly one of docile piety: “O Lord GOD, what will you give me, for I continue childless, and the heir of my house is Eliezer of Damascus?” (Gen 15:2). It is respectful (here and in v. 8 are the only instances where Abram addresses God as “Lord Yahweh”), but it is also forthright. After all, what reward has Yahweh given Abram to this point? Back in Gen 12:1–3 Yahweh had promised Abram (a) land, (b) many descendants, and (c) God’s blessing. According to Abram’s explicit statement, “You have given me no offspring” (lit. “seed,” זרע, v. 3). And he has yet to receive any land. In fact, he as much as admits later that he had to leave “my land” and “my kindred” back in northern Mesopotamia (Gen 24:4). As for blessing, there is little that the narrator has explicitly noted. While he describes Abram as “very rich in livestock, in silver, and in gold” (Gen 13:2), he is clear that Abram obtained this wealth by his own conniving (“Say you are my sister, so that it may go well with me because of you,” Gen 12:13, 16). On the other hand, the narrator is also explicit that Yahweh had protected “Sarai, Abram’s wife” at least (Gen 12:17, and not Abram?). Since Yahweh’s original promise in Gen 12:1-3, the first mention of Abram’s being “blessed” comes from Melchizedek, who “blessed him and said, ‘Blessed be Abram by God Most High’” (Gen 14:19). While this is formally a wish for blessing, and not a report of God’s blessing, Melchizedek also confesses, “Blessed be God Most High, who has delivered your enemies into your hand!” By implication, God has blessed Abram with military deliverance. And also by implication, this time we hear from Abram himself, “God Most High, possessor of heaven and earth” (קנה, my translation) has “made Abram rich” (Gen 14:19, 22-23).

Because of Abram’s direct question in Gen 15:2, Yahweh gets more specific about this promise of descendants: “This man [Eliezer of Damascus] shall not be your heir; no one but your very own issue shall be your heir” (Gen 15:4). For the first time it becomes clear that Abram himself will father a descendant and heir. Next, in a boldly intimate scene, Yahweh graphically portrays their future numbers: “He brought him outside and said, ‘Look toward heaven and count the stars, if you are able to count them.’ Then he said to him, ‘So shall your descendants (lit. “seed”) be.’” At last Abram knows that his “seed” will be his own child.

Although Yahweh’s promise is more specific, it is not specific enough to prevent the next regrettable development: “Now Sarai, Abram’s wife, bore him no children. She had an Egyptian slave-girl whose name was Hagar, and Sarai said to Abram, ‘You see that the LORD has prevented me from bearing children; go in to my slave-girl; it may be that I shall obtain children by her.’ And Abram listened to the voice of Sarai” (Gen 16:1-2). As shocking as the proposal is, especially coming from the wife, it appears to reflect customary practice of that culture. While Sarai’s proposal may have offered a utilitarian solution, it brings considerable grief and dysfunction to the ancestral family. After Hagar conceives, she gloats over Sarai, who in turn “dealt harshly” with her so that “she ran away from her” (Gen 16:4-6). This hostility requires two interventions from “the angel the Lord” (Gen 16:7-15; 21:8-21).

Info Box 9.4: Semitic Cultural Practice of Providing a Surrogate

Legal texts roughly from Abraham’s time period (the early second millennium BC) reflect the custom of a barren wife providing a surrogate to her husband in order to bear children. A marriage contract from a 19th century BC Assyrian colony in Anatolia reads, “Laqipum has married Hatala …. If within two years she (i.e., Hatala) does not provide him with offspring, she herself will purchase a slavewoman, and later on, after she will have produced a child by him, he/she may then dispose of her by sale wheresoever he pleases” (ANET, 543, §4; see further K.A. Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament, p. 325). The Code of Hammurabi (18th century BC) reads, “If a man marries a nadītu [a priestess], and she gives a slave woman to her husband, and she (the slave) then bears children, after which that slave woman aspires to equal status with her mistress — because she bore children, her mistress will not sell her; (but) she may place upon her the slave-hairlock and reckon her with the slave women” (COS, 2.131, §146; see also §§144, 147 and COS, 3.101B). A text from Nuzi in northern Mesopotamia (15th century BC) reads, “if Kelim-ninu does not bear, Kelim-ninu shall acquire a woman [or “slave girl”] of the land of Lullu as wife for Shennima, and Kelim-ninu may not send the offspring away” (ANET, p. 220). (While Nuzi is geographically remote from Canaan, the city’s population was predominantly Hurrian, a people group who had migrated from the mountains of Armenia southeastward into Mesopotamia and southwestward into Syria-Canaan hundreds of years earlier. We should also recall that Abraham’s homeland of Haran and Aram-naharaim was also in northern Mesopotamia. See Gen 12:4-5; 24:4, 10.)

It is not until 24 years after Yahweh’s initial promise to Abram (Gen 12:4; 17:1) that Yahweh finally identifies both parents of his “seed” (Gen 17:7-10). As wonderful as Yahweh’s promise about Sarah is—”I will give you a son by her”—Abram responds with disbelief: he “fell on his face and laughed (וַיִּצְחַק), and said to himself, ‘Can a child be born to a man who is a hundred years old? Can Sarah, who is ninety years old, bear a child?’” (Gen 17:17). And despite the former grief brought upon his family, he laments, “O that Ishmael might live in your sight!” At this point Yahweh becomes insistent: “No, but your wife Sarah shall bear you a son, and you shall name him Isaac (יִצְחָק). I will establish my covenant with him as an everlasting covenant for his offspring after him” (Gen 17:19; cf. 17:21; 21:12). As the Hebrew text makes clear, Yahweh marks Abram’s disbelief by branding his son with a name that means, “he laughs.” Yahweh’s chagrin is also suggested by the narrator’s closing comment: “And when he had finished talking with him, God went up from Abraham” (Gen 17:22). At long last Yahweh’s promise regarding Abraham’s “seed” is made clear, and the narrator has made no effort to whitewash the weaknesses of the human actors.

One wonders why Yahweh was not clear from the beginning that both Abraham and Sarah would parent “his seed,” especially considering their being “old, advanced in age” and Sarah being past menopause (Gen 18:11; 24:1). Apart from Yahweh’s explicit disclosure, why should anyone expect they should bear a child themselves? The biblical text does not answer these questions, but it does show us that we should not expect that even when God does reveal his will to us that each decision should be clear and lead to positive consequences.

► We should not expect that even when God does reveal his will that each decision should be clear and lead to positive consequences.

It may be more than coincidence that Yahweh’s first two speeches about “your offspring/seed” occur in immediate connection with Lot, Abram’s nephew. Immediately after Yahweh’s initial command, “Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you,” the narrator tells us, “so Abram went, as the LORD had told him” (Gen 12:1, 4). Abram’s obedience is clear, but we are also told that “Lot went with him.” As phrased, this action is Lot’s. But the next verse reads, “Abram took his wife Sarai and his brother’s son Lot.” It would seem that it was Lot’s initiative to go with Abram, but then it was Abram’s decision to bring him along. It is at this point that Yahweh promises Abram, “to your offspring (or “seed”) I will give this land.” Later, the narrator explicitly makes the point that it is “after Lot had separated from him” that Yahweh delivers his second speech about Abram’s offspring/seed: “I will make your offspring like the dust of the earth” (Gen 13:14-16). Due to lack of clarity about the identity of Abram’s seed and how that should come about, it would appear that Abram has been hedging his bets by bringing his nephew as a potential heir. Moreover, it is after Lot’s apparent return to Sodom (Gen 14:16; 19:1) that Abram laments, “You have given me no offspring, and so a slave born in my house is to be my heir” (Gen 15:3).

These observations raise another question: while Abram obeyed Yahweh by going from his land/country (Gen 12:1, 4), did Uncle Abram ignore the command to go from his “kindred” and his “father’s house” by bringing his nephew? So it would seem, especially in view of the consequences Abraham and his descendants would have to face. The narrator expends several chapters to spell this out. The next chapter tells of the feuding that erupted “between the herders of Abram’s livestock and the herders of Lot’s livestock” (Gen 13:7) and the consequent separation of uncle and nephew. The next chapter records how Abram endangered his own life by engaging in a military rescue of Lot (Gen 14:12, 16). It is Lot’s presence in Sodom that brings Abram’s intercession for the city and its subsequent destruction centerstage in the story (Gen 18:16-19:29). Finally, Lot himself is the reason for the birthing of the peoples of Moab and Ammon (Gen 19:30-38), who will later become the sworn enemies of Israel (Deut 23:3-6).

Nonetheless, Yahweh most certainly does not abandoned Abram to his own devices. In spite of Abram’s taking one of his “kindred” with him, Yahweh repeatedly reassures Abram and even heightens his promises (Gen 13:14-17; 15:1ff., etc.). In fact, Yahweh discloses his intentions to Abraham as a confidant (Gen 18:17-19) and gives him the privilege of making intercession. Yahweh’s rescue of Lot was specifically because “God remembered Abraham” (Gen 19:29). Even though Abraham’s obedience was not complete, Yahweh faithfully remains “the God of Abraham.”

It is ironic that Yahweh offers the promise, “Do not be afraid, Abram, I am your shield” (Gen 15:1), only after Abram has returned from battle. One might have preferred hearing this promise of military protection in Gen 14:1—before putting one’s life on the line. But it is noteworthy that Abram suffers the distress of battle and is reassured only later by Yahweh. Perhaps Yahweh’s point is that you should now realize from experience that “I am your shield.” The “torah” or “instruction” implicit here is that one may endure hardship with no reassurances from God until after one has passed through that hardship.

9.6. God the Covenant Partner and Victim (Gen 15)

► While Abraham's faith in God is commendable, he also wants to know that God will deliver on his promises.

Back in Chapter 12 Yahweh had promised to Abraham land and numerous descendants (Gen 12:1-2, 7). Three chapters later Yahweh promises, “your reward shall be very great” (Gen 15:1). We are not given the time span, though it is apparently within 10 years (see Gen 16:3.). As wonderful as this promise is, Abraham remains dubious: “O Lord God, what will you give me, for I continue childless, and the heir of my house is Eliezer of Damascus?” (Gen 15:2). He calls God to account, respectfully but forthrightly. To this point he has received little evidence that this deity lives up to his word. So Yahweh assures him, “This man shall not be your heir; no one but your very own issue shall be your heir” (Gen 15:4). And then with intimate condescension Yahweh “brought him outside and said, ‘Look toward heaven and count the stars, if you are able to count them…. So show your descendants be’” (Gen 15:5). Having addressed the issue of an heir, Yahweh reassures Abraham about the promise of land (future) by reminding him oftheir shared past (history): “I am the LORD who brought you from Ur of the Chaldeans, to give you this land to possess” (Gen 15:7). But once again Abraham responds with skepticism: “O Lord GOD, how am I to know that I shall possess it?” (Gen 15:8). We should not be hard on Abraham here, if we are honest with ourselves. But these expressions of Abraham’s hesitation (Gen 15:2-3, 8), appearing as they do both before and after Gen 15:6, make the claim of that verse all the more noteworthy: “And he believed the LORD; and the LORD reckoned it to him as righteousness.” In the New Testament this verse rightly marks Abraham’s exemplary faith (Rom 4:3; Gal 3:6; James 2:23), but the immediate context illustrates for us the nature of that faith. He is not the unwavering hero of faith that many Christians have imagined. Yet readers should take to heart that, wavering as Abraham’s faith is, this verse nonetheless judges that faith as sufficient and endorsed by Yahweh himself. Even when faith may waver in uncertainty, believers can still claim to reflect the faith of Abraham, which God approved. In the Old Testament true “faith” does not preclude the desire for certainty and evidence (“how am I to know?”). In the New Testament, faith and doubt may be opposites (Matt 21:21 // Mark 11:23; Rom 14:23; James 1:6), but even there faith and doubt may coexist (Matt 14:31; Mark 9:24).

Info Box 9.5: Paul’s Interpretation of Abraham

Some readers might suppose that my description of “Abraham’s faith” as “wavering” is a direct contradiction of Paul’s characterization of Abraham (esp. considering that Romans 4 is largely an exposition on Gen 15:6): “He did not weaken in faith when he considered his own body, which was already as good as dead (for he was about a hundred years old), or when he considered the barrenness of Sarah’s womb. No distrust made him waver concerning the promise of God, but he grew strong in his faith as he gave glory to God, being fully convinced that God was able to do what he had promised” (Rom 4:19-21). In context, Paul is taking a retrospective perspective and is speaking in ultimate terms in order to encourage his Christian readers to choose justification by faith, as distinct from justification by works of the law (see esp. Rom 4:2-5; 5:1). When Abraham’s life is viewed as a whole, he did ultimately choose the way of faith. But even in the verses just cited, Paul acknowledges that Abraham “considered his own body” and “considered the barrenness of Sarah’s womb,” thus showing that he was fully aware of Gen 17:17 (“Then Abraham fell on his face and laughed, and said to himself, “Can a child be born to a man who is a hundred years old? Can Sarah, who is ninety years old, bear a child?”). He also acknowledges that “faith” is something that “grows” and that one needs to be “convinced.” Paul is careful to note that the opposite of “faith” is not doubt, but “distrust,” which is an act of willful disbelief.

► In response, God ratifies his earlier promises (Gen 12:1-3) in a legal covenant/contract.

Once again, Yahweh remarkably concedes and provides Abraham with a measure of certainty through a strange, but powerfully symbolic, ceremony. It is precisely because of Abraham’s question in Gen 15:8 that Yahweh now formalizes his promises in a legal contract and guarantee or “covenant.” We should note that, as marvelous as this covenant ceremony is, it is a concession from God. In Gen 15:9 and following, Yahweh is responding to Abraham’s question of Gen 15:8. Up to this point Yahweh has given his “word” (esp. Gen 15:1, 4), but now Abraham asks for something more tangible. In addition to his verbal word, Yahweh volunteers to “sign on the dotted line” of a legal contract. Perhaps ideally one should take a person, such as God, at his word, but the Bible is realistic that sometimes people need legal guarantees.

Yahweh responds by commanding Abraham to bring certain animals. This may sound bizarre to our ears, but the passage implies that Abraham understood what Yahweh was initiating. After collecting these animals he proceeds, without further instruction, to “cut them in two, laying each half over against the other; but he did not cut the birds in two.” The story presupposes that this ritual is not newly revealed to Abraham nor unique to Yahwism. Later the narrator tells us, “a smoking fire pot and a flaming torch passed between these pieces. On that day the LORD made (lit. ‘cut’) a covenant with Abram” (Gen 15:17-18). What could this mean? This ritual is attested and elucidated by an ANE “land grant” of the same time period:

“Abbael [the master] swore the oath to Yarimlim [the subordinate] and cut the neck of a lamb, <saying:> ‘If I take back what I have given you <may I be cursed>’” (Alalakh Text 456, lines 39b-42 in COS 2.137).

Thus it appears that slaying the animal is to illustrate the fate of the one granting a promise, should he renege his obligation. He takes an oath by invoking a self-curse.

Info Box 9.6: Alalakh Text

The rituals in both Genesis 15 and this text from Alalakh occur in the context of a “land grant,” where a superior gives land to a subordinate (note esp. Gen 15:18). Likewise, both Abbael and Yahweh are the ones who invoke the self-curse. For further discussion see Richard S. Hess, “The Slaughter the Animals in Genesis 15,” He Swore an Oath: Biblical Themes from Genesis 12-50 (Cambridge: Tyndale House, 1993), p. 57.

► Remarkably, Yahweh "cuts a covenant" with Abraham in a ritual whereby he invokes a curse upon himself.

This ritual is nowhere else attested in the Old Testament (it is notably absent in Leviticus), except for a close parallel in Jer 34:18-19:

“And those who transgressed my covenant and did not keep the terms of the covenant that they made before me, I will make like the calf when they cut it in two and passed between its parts” (Jer 34:18).

Although Jeremiah’s 6th-century BC judgment oracle has no direct connection to Abraham, it also sheds light on the meaning of the ritual. King Zedekiah and his officials had “cut a covenant” to release all Judean slaves, but later reneged on this contract. In this prophetic oracle Yahweh threatens to execute the curse that the officials had invoked in their covenant/contract to release the slaves. Thus, when the superior who grants a promise passes between the pieces of the sacrifice, he invokes on himself the fate of the dissected animals, should he break his promise.

What is shocking in Genesis 15, of course, is that the superior who invokes a self-curse is none other than God himself! In unprecedented fashion Yahweh vows—by his very life—to keep his promise to Abraham. The notion of a deity threatening death upon himself sounds ridiculous until we open the pages of the New Testament: “Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us—for it is written, “Cursed is everyone who hangs on a tree”—in order that in Christ Jesus the blessing of Abraham might come to the Gentiles, so that we might receive the promise of the Spirit through faith” (Gal 3:13-14). The Son of God becomes both victim and victor over death and sin.

9.7. God the Monster? (Gen 22)

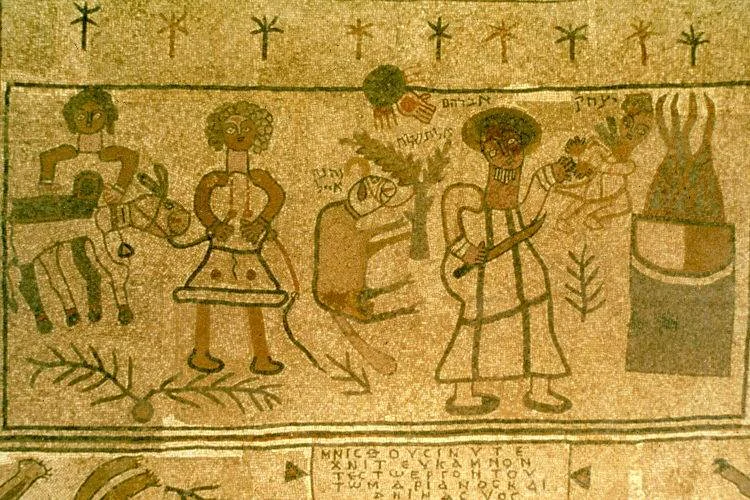

The Binding of Isaac Mosaic, Beth Alpha Synagogue (6th century CE)

The Binding of Isaac (Church of the Holy Sepulcher)

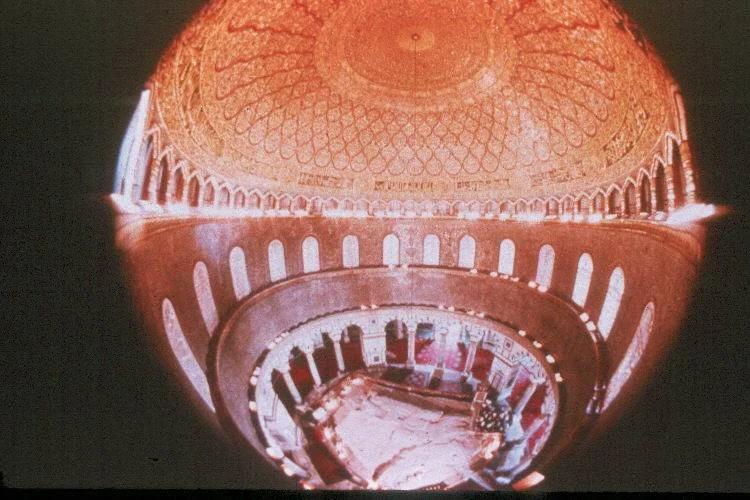

Dome of the Rock: Fish-Eye Interior View

► God tests Abraham by commanding him to offer his promised son as a burnt offering.

This is one of the most troubling chapters of the Bible. To hear it properly we must respect it as given to us and make no attempts to domesticate it by subconsciously rewriting it to conform to our theological expectations of what behavior we consider appropriate for God. We must let the narrative unfold the story for us and thus “forget” how it ends and what we know about God that Abraham does not know.

God had promised Abraham a son and he made good on that promise, but what few recognize is that Abraham had to wait 25 years (Gen 12:4; 21:5)! Now in the story of Gen 22 Isaac appears to be at least a teenager, so we are about 40 years from God’s first promise to Abraham.

Right at the start the narrator leaks some vital information to his audience: “God tested Abraham” (Gen 22:1). Otherwise, the story would be unbearable and put God in the midst of a bald contradiction. But we must remember, Abraham does not know this is a test. He thinks it is the real thing.

Next God gives a horrifying command: “Take your son, your only son Isaac, whom you love, and go to the land of Moriah, and offer him there as a burnt offering on one of the mountains that I shall show you.” This is not a kind speech reminding Abraham how precious Isaac is to him; it is a cruel speech demanding the surrender of what one loves the most. If we cannot hear the contradiction in God’s command, we cannot appreciate that this is indeed a “test.” God had been clear in his promise concerning this child: “… you shall name him Isaac. I will establish my covenant with him as an everlasting covenant for his offspring after him” Gen (17:19, and also Gen 17:21). And he repeats himself: “it is through Isaac that offspring shall be named for you” (Gen 21:12).

Were God to tell me to sacrifice my son, I would refuse. But I need to recall that I have a distinct advantage over Abraham: I know those passages in Leviticus, Deuteronomy, and the Prophets that Yahweh abhors child sacrifice (e.g., Lev 20:1-5; Deut 12:31; 2 Kgs 17:17; Jer 7:31; Ezek 16:20-21; 20:31). And I know that God is not fickle but faithful to his promises.

► What does Abraham know about this God? He makes big promises but has yet to deliver on them.

But what does Abraham know about God? He has grown up with a pagan heritage of many gods with conniving dispositions (Josh 24:2-3). His God is indeed a God of great promises (for many descendants, great blessing, and the land of Canaan), but Abraham has seen precious little evidence that he delivers on those promises. In fact, God is now reneging on the one solid piece of evidence Abraham has, namely Isaac.

Info Box 9.7: What has God actually done for Abraham?

Yahweh had protected Sarai and Pharaoh’s harem, but Abraham became wealthy by his own conniving (Gen 12:16-17). There is no hint of divine intervention and Abraham’s rescue of Lot and battle with the four-king alliance (Gen 14). God indeed made a covenant with Abraham, but this is simply a legal ratification of the earlier verbal promises, not an actual delivery on those promises. In the Sodom and Gomorrah incident Yahweh dramatically demonstrated that he judges sin (Gen 18-19).

Not only is Yahweh’s character in this narrative puzzling but also Abraham’s. He shows no hesitation to obey this demand for child sacrifice (see Yahweh’s retrospective in Gen 22:18). In fact, he “rose early in the morning” to go “to the place in the distance that God had shown him.” Back in Genesis 18 Abraham had gone to considerable lengths to intercede for his nephew Lot, but now for his son Isaac there are no objections recorded. And where is Sarah in this story? Ironically her next mention in Genesis appears in the next chapter where she dies (Gen 23:1-2).

And what does Abraham mean when he says, while he and Isaac take leave from the servants, “Stay here with the donkey; the boy and I will go over there; we will worship, and then we will come back to you” (Gen 22:5, emphasis mine)? Given what we know about Abraham’s character, especially his truth telling (e.g., “Say you are my sister,” Gen 12:13, 19; 20:2, 5, 12), we are not sure whether he is using a ploy to avoid confrontation with his servants or he believes that God will somehow spare or restore Isaac. Isaac’s question, “the fire and the wood are here, but where is the lamb for a burnt offering?,” reveals that Abraham has kept a deep secret. His reply is equally enigmatic: “God himself will provide the lamb for a burnt offering, my son.” Again, is it a ploy to postpone confrontation or is it an expression of hope that God will call the whole thing off?

Abraham’s actions become unambiguous in Gen 22:9-10, where he clearly has every intention of practicing child sacrifice: “When they came to the place that God had shown him, Abraham built an altar there and laid the wood in order. He bound his son Isaac, and laid him on the altar, on top of the wood. Then Abraham reached out his hand and took the knife to kill his son.”

► God's test of Abraham is resolved when he discovers that Abraham does fear God.

Yet at the last moment Yahweh intervenes: “But the angel of the LORD called to him from heaven, and said, ‘Abraham, Abraham!’ And he said, ‘Here I am.’ He said, ‘Do not lay your hand on the boy or do anything to him; for now I know that you fear God, since you have not withheld your son, your only son, from me’” (Gen 22:11-12).

To appreciate the theology of this passage we must respect the literary form in which it is packaged, namely a narrative full of tension, suspense, and apparent contradiction. If we cannot appreciate the horror of Genesis 22, we have missed the point.

Info Box 9.8: Søren Kierkegaard, a Danish existenialist (19th century), retells Genesis 22

“It was early in the morning, Abraham arose betimes, he had the asses saddled, left his tent, and Isaac with him, but Sarah looked out of the window after them until they had passed down the valley and she could see them no more. They rode in silence for three days. On the morning of the fourth day Abraham never said a word, but he lifted up his eyes and saw Mount Moriah afar off. He left the young men behind and went on alone with Isaac beside him up to the mountain. But Abraham said to himself, ‘I will not conceal from Isaac whither this course leads him.’ He stood still, he laid his hand upon the head of Isaac in benediction, and Isaac bowed to receive the blessing. And Abraham’s face was fatherliness, his look was mild, his speech was encouraging. [I suppose that at first Abraham looked upon Isaac with all his fatherly love; his venerable countenance, his broken heart, has made his speech the more impressive, he exhorts him to bear his faith with patience, he has let him darkly understand that he the father suffered from it still more. However that was of no avail.] But Isaac was unable to understand him, his soul could not be exalted; he embraced Abraham’s knees, he fell at his feet imploringly, he begged for his young life, for the fair hope of his future, he called to mind the joy in Abraham’s house, he called to mind the sorrow and loneliness. Then Abraham lifted up the boy, he walked with him by his side, and his talk was full of comfort and exhortation. But Isaac could not understand him. He climbed Mount Moriah, but Isaac understood him not. Then for an instant he turned away from him, and when Isaac again saw Abraham’s face it was changed, his glance was wild, his form was horror. He seized Isaac by the throat, threw him to the ground, and said, ‘Stupid boy, dost thou then suppose that I am thy father? I am an idolater. Dost thou suppose that this is God’s bidding? No, it is my desire.’ Then Isaac trembled and cried out in his terror, ‘O God in heaven, have compassion upon me. God of Abraham, have compassion upon me. If I have no father upon earth, be Thou my father!’ But Abraham in a low voice said to himself, ‘O Lord in heaven, I thank Thee. After all it is better for him to believe that I am a monster, rather than that he should lose faith in Thee’” (Søren Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling and Sickness unto Death [Princeton: Princeton, 1954], p. 27; the portion in square brackets above is from p. 11).

Such biblical stories are not mere history. They are told because they reveal God and how he acts with his people. The narrator tells us not just about the distant past but also about how God may appear to the readers of this story. God still tests his people, and in times of trial we may feel he is a monster, precisely because, like Abraham, we do not know it is a test.

We may never come to terms with Genesis 22, but if we can at least acknowledge it, we are better prepared to face any darkness in our future.

Even after the angel the Lord had stayed Abraham’s hand and repeated to him the promise of innumerable descendants, we would probably feel that God has jerked us around just to “test” us, if we were to walk in Abraham’s shoes. It would be difficult to maintain respect for God.

► For Christians, Abraham's offering of his son Isaac foreshadows Good Friday.

That is, until we turn to the pages of the New Testament, where the apostle Paul raises the question: “He who did not withhold his own Son, but gave him up for all of us, will he not with him also give us everything else?” (Rom 8:32). We have now come full circle from “God the Monster?” of Gen 22. Only this time the father did not withdraw his hand from slaying his son. This was no test; he went through with the sacrifice (cf. Isa 53:10). And so we see that Genesis 22, cruel though it was, is a foreshadowing of the cruelty our heavenly Father endured for our sakes on Good Friday. The God who demands all gives all. He may appear to be a monster, yet he surprises us with gifts beyond our wildest imagination.

And we have also come full circle from the strange covenant ritual of Genesis 15, when God himself passed between the dissected pieces of the animal sacrifices and invoked on himself the curse of the breached covenant.

As Paul says elsewhere, “Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us—for it is written, “Cursed is everyone who hangs on a tree”— in order that in Christ Jesus the blessing of Abraham might come to the Gentiles, so that we might receive the promise of the Spirit through faith.(Galatians 3:13–14).

9.8. God Behind the Scenes (Gen 37-50)

► Unlike the Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob stories, God is "offstage" and the plot is driven by human decisions and actions.

In the Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob stories (Gen 12-36; 38) Yahweh speaks and acts in virtually every chapter, but in the Joseph stories (Gen 37; 39-50) he speaks to no one directly, with the exception of Jacob (Gen 46:1-4). The closest we get is Pharaoh’s dream, which Joseph interprets to be a revelation from God (Gen 41:25, 28). In four instances—all within the story about Potiphar’s household—the narrator tells us “Yahweh was with Joseph” so he becomes “successful” (e.g., Gen 39:2, 3, 21, 23). In the same chapter Yahweh gives his “blessing” “for Joseph’s sake” (Gen 39:5). These are more general statements that account for Joseph’s sudden turn of events: from being sold into slavery to being promoted as household overseer. Otherwise, the narrator reports no direct interventions from God. The Joseph story is a very human story, where people drive the action, dialogue, and plot.

The Joseph story is well known. He was sold by his brothers as a slave, but then rose to become household overseer, only to be cast into prison. Then after being summoned before Pharaoh himself, interpreting his dream, and offering counsel, be becomes the second most powerful person in Egypt. Then during the famine, the brothers who betrayed Joseph must come to him to buy grain, and here he reveals himself: "I am your brother, Joseph, whom you sold into Egypt. And now do not be distressed, or angry with yourselves, because you sold me here; for God sent me before you to preserve life…. God sent me before you to preserve for you a remnant on earth, and to keep alive for you many survivors. So it was not you who sent me here, but God; he has made me a father to Pharaoh, and lord of all his house and ruler over all the land of Egypt. Hurry and go up to my father and say to him, ‘Thus says your son Joseph, God has made me lord of all Egypt; come down to me, do not delay” (Gen 45:4b-5, 7-9). Here God’s interventions are revealed, not by God’s own speech or by the sacred narrator but in Joseph’s own retrospective interpretation. Given the reality of the famine, had Joseph’s brothers not betrayed him and Joseph not risen to a position of influence, Jacob’s family would have had no special access to the stores of Egypt.

► It is Joseph's testimony that reveals God's providence in the midst of human intrigue.

Later Joseph reminds his brothers, "Even though you intended to do harm to me, God intended it for good, in order to preserve a numerous people, as he is doing today” (Gen 50:20). This verse sounds like an OT version of Rom 8:28: “We know that in all things God works for the good of those who love him, who have been called according to his purpose.” In the Joseph story we see that God is in control when people are least aware of it. We see the mystery of God at work in human decisions and actions. Some might consider Joseph a spiritual inferior to his ancestors, but we learn that God works as providentially in Gen 37-50 as he did in Gen 12-36. The ways of God can’t be put down to a single scheme. God works dramatically for some people and more behind the scenes for others. We may hear his voice, or we may only see his footprints as we look back over our lives.