Psalms

The Psalms scroll from Qumran at the Dead Sea (11QPsa), columns 16–17, containing portions of Psalms 136, 118, and 145

The Book of Psalms makes clear categorization and dogma impossible. No book of the Bible has a wider scope than the Psalms. Its tradition and literary history spans from the pre-monarchic period to well into the Second Temple period. It represents national circles as varied as the kingdoms of northern Israel and southern Judah and social circles such as the royal court, the priestly temple, and rural clan settings. Its literary genres travel from pre-monarchic victory songs to postexilic literary acrostics.

What is a Psalm?

► Generic observations indicate that psalms originally functioned as liturgies (set prayers) for typical needs and worship services.

Responsible readers of any document, and especially biblical texts, must respect the “ground rules” of that literature. In order to hear all that biblical texts may be saying and to avoid reading one’s own assumptions into them, the interpreter’s first act must be to listen to these texts on their own terms.

So we must be clear on how Psalms originally functioned in ancient Israel. Before examining specifics within the Psalms, we shall first make some general observations on the generic cues for how these ancient poems were meant to be interpreted and used in worship.

First, in contrast to the spontaneous prose prayers found in biblical narratives, the Psalms are tightly woven poetic compositions. Even prayer psalms reflecting life or death distresses (such as Psalms 13 and 22) exhibit intricate literary echoes and structures. While their references to singing imply oral performance, their intricate wording implies that psalms were literary compositions, not spontaneous ad hoc cries of help or praise.

Second, the identities of “I,” “we,” and “they” (usually the enemies) are open-ended. Unlike the narratives of biblical history and even the poetic oracles of the prophets, the speaker’s opponents in the Psalms are rarely identified. Moreover, the circumstances reflected in the Psalms are portrayed with a variety of impressionistic images. The images applied to the opponents in Psalm 35, for example, reflect metaphors from a variety of social spheres: the battlefield, agriculture, hunting, robbery, legal accusation, carnivorous beasts, and social mockery.

The generic nature of psalms becomes apparent when we compare them to David’s poetic lament in 2 Samuel 1, which names its subjects (Saul and Jonathan), their enemies (the Philistines), the location (Mount Gilboa), and the circumstances of battle. It is significant that this poetic lament has been transmitted to us, not in the book of Psalms, but in “The Book of Jashar.” The open-ended language of the Psalms implies they were written for typical, recurring occasions in the life of God’s people.

Third, while each of the 150 Psalms is unique in its own right, most of them follow regular literary patterns, as seen in the psalmic genres described below. This is not to suggest that the biblical psalmists had to follow anything like the style guide of the Jerusalem temple publishing house, but clearly traditional conventions of poetic expression prevailed over individual invention, as in “free verse.”

Gerard van Honthorst, King David Playing the Harp, 1622

Fourth, many psalms contain liturgical and ritual allusions. Most hymns begin with plural imperatives that serve as a “call to worship” to a congregation (such as, “Hallelu-Yah!,” which means, “Ya’ll praise Yahweh!”). Changes of address (from addressing God directly, “you,” to referring to Him in the third person, “He”) and speaker (evident, e.g., from a question-answer format) suggest a congregational setting. Many psalms refer to the temple on Mt. Zion and to ritual processions (e.g., Psalms 24 and 68) and sacrifices that accompanied the performance of the psalm. References to lyres and other musical instruments imply musical performance.

These observations imply that the psalms were not spontaneous, free verse, written for singular occasions, but were carefully crafted liturgies written for recurring, typical human needs and for services of worship. In other words, the psalms formed a kind of ancient prayer and hymn book.

An analogy with Christian hymn books and especially denominational prayer books may be helpful. As The Book of Common Prayer contains regular liturgies in which all worshipers participate during the liturgical year, such as Morning Prayer, the Lord’s Supper, and Easter Sunday, so the Book of Psalms contains liturgies, such as hymns and the Songs of Zion, that were performed at annual pilgrimage festivals, such as Passover, Feast of Weeks, and Tabernacles. As the back of the prayer book contains special prayers and thanksgivings for particular groups and needs (such as governments, schools, the unemployed, and the sick), so the Book of Psalms contains Royal Psalms reserved for the king’s coronation and prayer psalms for individual needs as they arise. These individual prayers may have been invoked in local, private ceremonies and even at the bedside of the sick.

► Psalms are not autobiographical, reflecting the poet’s feelings; they are liturgical, leading the worshiper’s experience.

Recognizing that most psalms were originally set prayers, intended to guide worshipers in articulating their cries of distress and their celebrations of God’s goodness and power, means that it would be inappropriate to read them simply as autobiographical poems expressing the feelings of their composers. Rather, they are meant to lead the worshiper’s experience of God through times of trial and times of worship.

As set prayers, the psalms put words in the worshiper’s mouth, thus encouraging each to reflect on and to incorporate healthy dependency on and acknowledgment of God. They thus implicitly have educative and behavior-modifying functions. As the psalms were hammered out over generations of people living with God, they are deeply personal, not as expressing an individual’s experiences, but as evoking the experiences that should typify the people of God.

Throughout their biblical history we shall discover that the psalms have been transformed to fit a variety of functions: (a) liturgies, (b) meditative literature, (c) “Davidic” prayers (see the sidebar, “David and the Psalm Superscripts”), and (d) prophecies (especially the royal psalms).

History of Psalms and Their Traditions

The genres of poetic hymns and prayers were ancient even before the first biblical psalm was written, as evidenced by their long history in Egypt and Mesopotamia. Enḫeduanna, the daughter of Sargon, king of Akkad (ca. 2300 BC), and a priestess herself, had compiled 42 temple hymns from Sumer and Akkad (see Sparks, “Hymns, Prayers, and Laments,” 86). The feature of poetic parallelism is attested in Egypt a thousand years before it appears in Israel.

Pre-Monarchic Hebrew Poems

Attempts at dating individual psalms is problematic. We have seen that they are, by their very nature, generic and thus intentionally avoid ties to particular events or experiences. The best we can hope, at this point, is to look for clues that associate a particular psalm with one of the three general periods of Old Testament history, namely the pre-exilic, exilic, and postexilic eras.

Probably the oldest texts of the Hebrew Bible are ancient poems found outside the Psalter. Two are tribal blessings: the blessing of Jacob (Gen 49:2-27) and the blessing of Moses (Deut 33:2-29). Two are victory songs: the Song of the Sea (Exod 15:1-18) and the Song of Deborah (Judg 5:2-31). There are also the Song of the Ark (Num 10:35–36) and the songs in “The Book of the Wars of the Lord” (Num 21:14), among others. The four Balaam Oracles (Num 23–24) and the Song of Moses (Deut 32:1-43) may possibly be pre-monarchic, or at least early monarchic. “The book of Jashar” also contained poems that are at least early monarchic (Josh 10:12–13; 2 Sam 1:17–27).

First Temple Psalms

Model of Herodian Temple (first century CE). Unlike modern churches or synagogues, which serve as buildings where worshipers gather, the Jerusalem temple was God's "house." The Hebrew word for "temple" also means "palace." Men, women, and Gentiles would gather in the forecourts, seeking God's "face," which is idiomatic for seeking a royal audience at the palace.

► Psalms that allude to the cherubim-ark, the Zion tradition, or the king and his armies must stem from the pre-exilic period.

The following clues can be used to identify psalms that are evidently pre-exilic: allusions to a king of Israel/Judah (notably the Royal Psalms), allusions to the armies of Israel/Judah, the Songs of Zion that speak of its inviolability, and allusions to the cherubim-ark as a visible symbol used in ritual processions. As the prior tradition on which most of these psalms are based is that of divine cosmic kingship, we shall begin with the psalms that allude to the symbolism of the cherubim-ark, a pre-exilic object symbolizing Yahweh’s throne-chariot and footstool. Most of the prayer psalms of the individual were probably pre-exilic, as we shall see that some individual prayers contain later insertions of corporate traditions, probably added in the exilic and postexilic periods. No doubt other psalms originated in the First Temple Period, but as they contain no particular clues linking them to a historical period, we shall not include them in this historical survey.

King Ahiram's sacrcophagus (Phoenician, 13th BCE). Cherubim thrones were familiar symbols in the Semitic culture.

► The most popular deity in the ANE was "the god of the skies," who provided rain for farmers and pastoralists. In the common Semitic storyline, the Cloudrider prevails over the chaotic waters and thus becomes the cosmic king, whose palace/temple resides on the sacred mountain.

Cherub in the palace of the Assyrian governor (Arslan Tash, 9th/8th BC). Cherubs were composite creatures pointing to the otherworldly realm. The human face signified wisdom, the lion's forequarters strength, the bull's hindquarters procreation, and the eagle's wings mobility.

(a) Psalms alluding to the cherubim-ark. Arguably the most sacred symbol associated with God’s presence was the cherubim-ark. The cherubim, whose inner wings touched each other, symbolized the throne on which Yahweh sat invisibly (Pss 80:1; 99:1). As winged beings, they could also symbolize His “chariot” that He rides in the clouds/skies (Pss 18:10; 104:3; 1 Chr 28:18). Underneath His cherubim-throne, the ark symbolized His “footstool” (Ps 132:7–8; 99:5; 1 Chr 28:2).

The ritual procession visible to the worshipers in Psalm 68 (Ps 68:24–27) is initiated by the “Song of the Ark” (Num 10:35), echoed in the psalm’s opening verse, and climaxes in the ark’s “ascent” into the sanctuary (Ps 68:17–18, 24). The processional “ascent” of Yahweh’s symbolic “throne” amidst the congregation’s “shouting” is also echoed in Psalm 47 (see Ps 47:8), which opens with imperatives for the congregation to clap and shout (Ps 47:1) and later reports that “God has gone up with a shout” (Ps 47:5, 9; cf. Josh 6:5, 20; 1 Sam 4:5; 2 Sam 6:15). Similarly in Psalm 89:13–17, Yahweh’s symbolic “throne” leads His people in procession accompanied by “shouting.” Psalm 24 portrays the entry of “the King of glory” through the gates upon His sacred mountain, His presence being symbolized presumably by the cherubim-ark, on which “Yahweh of hosts” sat invisibly enthroned (see 1 Sam 4:4; 2 Sam 6:2).

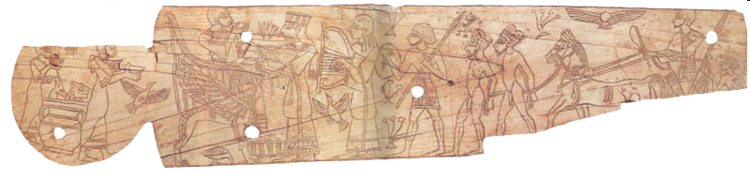

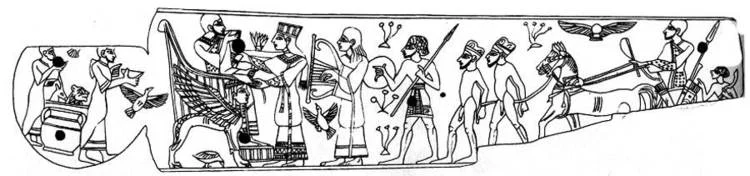

Canaanite "cherubim throne" ivory found at Megiddo (LB, ca. 1200 BCE, Phoenician design)

The principal tradition underlying Yahweh’s portrayal in these psalms is that of divine cosmic kingship. In Psalm 68 “the rider of the clouds” (Ps 68:4) and “of the skies/heavens” thunders with “his mighty voice” (Ps 68:33–34) and provides rain (Ps 68:8–9).

Preceding the description of the procession of Yahweh’s throne in Psalm 89 are verses claiming that Yahweh is incomparable in the royal council among the divine beings (lit. “sons of the gods,” cf. Ps 29:1) and rules the sea and crushes the sea monster Rahab, thereby establishing world order. In Psalm 24 the earth belongs to the Lord, as distinct from other claimants, because He established it upon “the seas” and “the rivers.” As a result, Yahweh, “a warrior of war,” enters through the gates as “King of glory.”

Cherub guarding entry into theʿAin Dara temple in Syria

Several other psalms share this constellation of motifs wherein Yahweh is portrayed as the God of the skies/storm (a) who prevails over the waters/seas and rivers (rendered “floods” in some English translations), (b) who is then acclaimed as “king,” and (c) whose temple/palace (hekal) resides on the sacred mountain (Pss 29; 74; 93; 97; 104).

This storyline is unlike the historical one familiar from the Pentateuch, where the God of Abraham brought Israel out of Egypt to His sacred mountain at Sinai, where He disclosed His covenant and law, and then led His people through the wilderness to the promised land. But this cosmic storyline is common in the ANE, most notably in the Baal Myth of the eastern Mediterranean (KTU 1.2.4.7–32; 1.4.6.16–38) and in the Enuma Elish of Mesopotamia (4.31–134; 5.85–88, 117–124). Psalm 29, in fact, contains some expressions that are more at home in the wider Canaanite world than in Israel’s (e.g., the “sons of gods” in Ps 29:1, the geographic word pair of Lebanon and Sirion, the sevenfold thunderous voice that comes with lightning, and the frequent alliteration with the consonants of Ba’al).

Evidently the biblical psalmists spoke through the Semitic cultural idiom of their time to acclaim Yahweh as the true divine king who vanquishes the forces of chaos and so establishes “right order” (צֶדֶק, tsedeq or צְדָקָה, tsedaqah). They did, however, extend this idiom in revealing ways.

Psalm 29 after hymning the cosmic king’s strong, earth-shaking voice, closes with a petition that is uniquely Yahwistic: “may Yahweh give strength to his people; may Yahweh bless his people with peace.” This seemingly random power displayed in a violent thunderstorm is now to be channeled specially to His people for their well-being.

(b) Songs of Zion. The Songs of Zion are an extension of the divine kingship tradition. They commemorate the sacred mountain of the God of the skies (76:2, 8) who utters His thunderous voice (46:6). In fact, Mount Zion is explicitly compared to “the height of Zaphon” (48:1–2), which was the sacred mountain of Baal to the north in modern-day Syria (KTU 1.3.3.28–31).

Another Song of Zion describes a “river whose streams make glad the city of God, the holy habitation of the Most High” (46:4) in terms that echo “the mountain of El,” which lies “at the source of the rivers, amidst the springs of the deeps” (KTU 1.4.4.20–23).

(c) Royal Psalms. In the Royal psalms the fundamental tradition legitimating Davidic rule is, of course, the Dynastic Oracle (Ps 89:19–37), but even here David’s political kingship is predicated on Yahweh’s cosmic kingship, hymned in verses 5–18. Similarly in Psalm 2, the source for the prophetic oracle, “I have consecrated my king upon Zion my holy mountain,” is identified as “the one seated in the heavens/skies.”

In royal psalms referring to battle, Yahweh’s saving help is both from “Zion” (Ps 20:2) and “from his holy heavens/skies” (Ps 20:6). The king’s rescue is based on a theophany of the God of the skies, who “rode on a cherub and flew” (Ps 18:7–15).

(d) Psalms alluding to Israel’s armies. These psalms draw from traditions principally found in the ancient victory songs, not from the Pentateuch.

In Psalm 44 Israel clearly has “armies,” who are defeated in battle, a feature that limits its origins to the pre-exilic period. It explicitly invokes the historical memory of the conquest of Canaan (Ps 44:1–3). But much of the terminology echoes not the book of Joshua but the ancient Song of the Sea, where God’s agency overshadows any efforts of the Hebrews (Exod 15:6, 9, 12, 16–17).

Psalm 80, which refers to Yahweh’s cherubim-throne and to Israel’s king, portrays a battle defeat in the image of a wild boar that feeds on an unprotected vine that Yahweh had “uprooted” from Egypt and “planted” in the land. This portrayal of the exodus and conquest is unlike the Pentateuchal narrative, but it likely combines pastoral images from Jacob’s blessing of “Joseph” (Gen 49:22–26) and the Song of the Sea (Exod 15). As the divine Shepherd leads “Joseph” in the psalm’s opening invocation, so God is named Shepherd (Gen 49:24) and “leads” His people to His sacred sheepfold (Exod 15:13) in these two ancient poems. As Joseph is likened to a fruitful bough with spreading branches (Gen 49:22), so God’s people are likened to a vine “planted” (Exod 15:17) with overflowing branches in Psalm 80.

► Prayers of the individual are based on the “my God” tradition, where one’s personal, guardian deity is expected to answer when called upon.

(e) Prayers of the Individual. The prayer psalms of the individual lack allusions to the corporate traditions evident in other psalms. They reflect a much simpler piety, which is expressed in their favorite divine title, “my God.”

Claims to having a personal, guardian deity are not unique to ancient Israel (see, e.g., “Prayer of Kantuzilis,” ANET, 400–401, and “Man and his God,” ANET, 589–91). But what is exceptional to these biblical psalms is that the Israelite’s personal, guardian deity is none other than Yahweh, the Most High who is incomparable to all spiritual beings.

Simply put, the substance of this tradition is that “my God” answers when called upon (see esp. 22:1–2, 9–10; 38:15; 140:6). This epithet appears in immediate connection with the petitioner either calling, trusting, or praising. The obligation of “my God” is to answer with deliverance, especially from premature death.

(f) Summary. The key function of these psalmic liturgies was to serve as songs that lead to prayer and the worship. Their interest lies in promoting an encounter with and an experience of the Transcendent. And so as poetry, they engage imagination. At Yahweh’s temple-palace the most ready metaphor is that of Yahweh as divine king. Where the pre-exilic psalms do echo earlier historical traditions, it is usually found in the ancient poems of the Song of the Sea (Exod 15), the Song of Moses (Deut 32), the Blessing of Moses (Deut 33), and the Song of Deborah (Judg 5).

While pre-exilic psalmody portrays Yahweh through the wider Semitic idiom of the God of the skies, it applies and develops it significantly in two distinct contexts.

First, Yahweh’s theophany is incorporated into “thanksgiving” for saving His people in military contexts (Ps 18; 68). Unlike Baal, Yahweh has “his people,” on whose behalf He intervenes (notably 29:11).

Second, the appearance of the God of the skies is to vanquish the wicked and to bring the establishment of justice in legal and moral contexts (Pss 50; 97; cf. Ps 68). In Israel the cosmic king establishes “right order” in both nature and human society. Yahweh saving activity, whereby He puts things “right,” extends into the human realms of history and justice.

Exilic Psalms and the Formation of Torah

Despite the temple’s destruction, the people of God still gathered for prayer during the exilic period (cf. Zech 7:3; 8:19). Exilic psalms echo some of the same traditions as the pre-exilic psalms. Both Psalms 74 and 79 lament the destruction the Jerusalem temple. Some of their expressions are reminiscent of the Song of the Sea (e.g., cf. 74:2 and Exod 15:13, 17). The hymnic segment that forms the basis of Psalm 74’s appeal for help remembers not the exodus in particular but the cosmic tradition of the divine king’s victory over the “sea” and “Leviathan” in the act of primeval creation (cf. 74:12–17 and KTU 1.5:1:1–4, where Baal is said to have vanquished Litan, and KTU 1.3.3.38–42, where Anat claims to have vanquished the serpent).

The prayer psalms of the individual do not incorporate national traditions until the exilic and postexilic periods. As noted above, the pre-exilic individual prayer psalms simply appeal to the tradition that “my God” answers when called upon. Corporate traditions and concerns, such as Zion and the exodus, do appear in the longer individual prayers of Psalms 22, 51, 69, 77 and 102, but in each case they are found in a discrete section within the psalm. These psalms—in their final, edited form—show a particular affinity to the exilic or early postexilic periods. Because the corporate traditions in these individual prayers appear to be later insertions, it is likely that earlier pre-exilic individual prayers were used as vehicles of lament for the communities of the exilic period—for the exiles in Babylon and for those who remained in Palestine. A clear example of this phenomenon, is Lamentations 3, which laments the destruction of Jerusalem using the literary form of individual lament.

► The Babylonian destruction of the temple shifted the focus of Israelite religion from temple to Torah, from liturgy to literature. The psalms survived as scrolls.

The Babylonian invasion of 587 BC brought a sudden end to the worship at the temple and the performance of psalms. Yet the fact that psalms performed at the Solomonic temple were retained in the Bible testifies to their being “rescued” on scrolls taken into exile. The psalms transitioned from liturgies to literature. This event marks a decisive turn in Israel’s religion, where the publication of their faith begins to shift from temple to Torah. Sacred space will give way to sacred scrolls. Seeing the temple symbols and rituals recedes, while hearing the word takes center stage. This development is evidenced in the postexilic “Torah psalms” and the formation of the “Book of Psalms,” discussed below.

During the pre-exilic period the psalms, as liturgies sung at the pilgrimage festivals, were the principal means for “publishing” the faith traditions of the people of Yahweh. Odd as it might sound, the notion of written Scriptures is anachronistic to the period of the Old Testament itself. When sacred scrolls were read aloud publicly, it is clear that their contents were not known to their audience. In Exodus 24:3–7 Moses read the “words” (20:1) and the “judgments” (21:1) of “the book of the covenant” (Exodus 20–23) to the generation of the exodus at Mount Sinai. Some 600 years later a high priest happened to discover “the book of the law”—probably an early edition of the book of Deuteronomy—hidden in the temple archives. Upon hearing it read aloud, King Josiah tore his garments after learning how far God’s people had strayed from God’s instruction. Over 160 years later and after the exile, the scribe Ezra read “the book of the law of Moses”—probably some form of the Pentateuch—in Nehemiah 8 and the people wept in response. In other words, the public reading or publication of written Scriptures was the exception, not the rule, during biblical times.

Hence, without temple, king, or land, a scribal culture became the driving force of Israel’s faith and religion. There was no centralized temple for the people of God to gather in worship to hear the Levitical choirs singing the liturgies and hymns from which they had learned of their faith during the pre-exilic period. Based on “the book of the law,” there developed the Deuteronomistic History (Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, 1–2 Samuel, and 1–2 Kings), books that share the language, themes, and theological perspective of Deuteronomy. In addition, other scrolls were compiled and edited into their nearly complete editions, such as the prophetic scrolls and the Pentateuch, later read by Ezra the scribe after the return from exile. The gradual shift from temple to torah can be illustrated in the postexilic Chronicler’s rewriting of first temple traditions found in 1–2 Kings. The pre-exilic phrases, “before me” (1 Kgs 8:25) and “the sight of the LORD” (1 Kgs 14:22), which principally refer to God’s presence at the Temple, are replaced with expressions referring to the God’s “law” or “torah” (2 Chr 6:16; 12:1).

Second Temple Psalms and the Book of Psalms

► Historical psalms in this period begin to echo the pentateuchal storyline. Yahweh, the cosmic king (God of the skies), becomes the political king over the nations. Yahweh's kingdom eclipses the former Davidic kingdom.

It is in psalms that are evidently postexilic (note, e.g., the petition for restoration from exile in 106:47 and the distinction between the houses of Aaron and Levi in 135:19–20) that the recital of the Pentateuchal storyline comes center stage (Pss 105; 106; 135; 136). In Psalm 135 the exodus-conquest sequence is prefaced with claims of Yahweh as cosmic king and God of the skies, implying that Yahweh’s cosmic sovereignty is now evidenced in the historical events of Yahweh’s “signs and wonders against Pharaoh” and His “striking down” of “many nations” (see the same pattern in Ps 136). In fact, the psalms that assert Yahweh’s sovereignty over the nations most forcefully are these two psalms, along with Psalm 115 (115:2–3; 135:5–6; 136:2–4). The combination of the cosmic tradition of Yahweh as divine king and the historical traditions of the pentateuchal storyline makes possible a symbiosis that generates a radically new theology of Yahweh. Yahweh, by becoming cosmic king over all divine beings in the heavenly council, becomes the political king over all nations, as evidenced by the repetition of the “kings” and “kingdoms” vanquished in Canaan and especially in Transjordan (135:10–11; 136:17–20). Hence, postexilic psalms are the first to refer to Yahweh’s “kingdom” (103:19; 145:11–13).

► "Torah psalms" emerge and the five-fold Book of Psalms is formed.

With the emergence of the scriptures and of pentateuchal Torah in particular, the Torah Psalms (Pss 1; 19:7–19; 119, discussed further below) reflect a newfound devotion to the meditative reading and study of the written Torah. Indeed, this development is evident in the final compilation of “the Book of Psalms” itself, wherein the earlier collections were compiled so that the Psalms became a Torah in their own right, mirroring the five books of the Pentateuch. Each book is marked off by a concluding doxology, such as “Blessed be the Lord, the God of Israel, from everlasting to everlasting! Amen and Amen” (41:13; and 72:18–19; 89:52; 106:48). The imperatival hymn of Psalm 150 serves as a doxology not only to Book V but also to the Book of Psalms as a whole. It was probably in this final stage of editing that Psalms 1 and 2 were placed at the head of the collection. Their lack of a psalmic superscript marks them off from the rest of the psalms in Book I. Psalm 1 had originally been a Torah Psalm, where “the law of the Lord” referred to the Torah of the Pentateuch. But now in its new location introducing the five books of the Psalms, it encourages meditation on the psalms as literature.

There are signs of even earlier stages of editing or redaction in the collection of the psalms. Noted in some of the psalms superscripts are “Davidic” psalms (Pss 3–41, except Pss 10 and 33; 51–65; 68–71; 86; 101; 103; 108–110; 138–145). This royal collection is distinct from the two Levitical collections found in the psalms of “the sons of Korah” (Pss 42–49; 84–85; 87–88) and the psalms of “Asaph” (Pss 50; 73–83). Korah psalms appear in Books II and III, and Asaph psalms principally in Book III. In Book V there are the “Psalms of Ascent” (Pss 120–134), which probably formed a prayer book for pilgrims to the postexilic temple. Generally, most of these later, postexilic psalms appear in Book V. An analysis of the Psalms scrolls found at the Dead Sea shows that the order of Psalms 1–89 had been fixed by the time of the Qumran community (before the first century BC), but the ordering of the remaining psalms was fluid until the end of the first century AD (see Peter Flint, The Dead Sea Psalms Scrolls. 135).

Overlapping Books II and III is the “Elohistic Psalter” (Pss 42–83), where the generic Hebrew name for God, “Elohim,” is preferred five times over the divine name Yahweh, usually rendered “the Lord” in most English translations. This is the opposite proportion found in the rest of the Book of Psalms. This preference is especially evident in duplicate psalms. Psalm 14 is nearly identical to Psalm 53, yet the former uses the divine name, Yahweh, and the latter the generic name, Elohim. The same is true for Ps 40:13–17 and Psalm 70. Although all four of these psalms are “of David,” these duplications imply that these Yahwistic and Elohistic psalms had circulated in separate collections before being collected into the Book of Psalms.

Info Box 1: David and the Psalm Superscripts

In the superscripts the phrase, “of David” (leDavid), occurs 73 times, 28 of which appear as “a Psalm of David” and 7 of which as “Of David. A Psalm.” Its precise meaning is ambiguous. The name “David” itself can mean either the historical individual or a king of the Davidic dynasty (Jer. 30:9; Ezek. 34:23–24; 37:24–25; Hos. 3:5). The prepositional phrase could be understood as “for David” or “(dedicated) to David.” It could also be interpreted as “(belonging) to David,” in the sense of ownership, either as author of the psalm or royal patron of the songs of the sanctuary at the nation’s capital. The phrase could also denote “belonging to a Davidic collection,” thus reflecting the royal patronage of the temple, as distinct from the Levitical collections of Asaph and Korah. We cannot assume that this Hebrew preposition (l) denotes authorship, because the same preposition appears in the phrase, “to/for the (choir) director/overseer/supervisor,” which appears in many of the same superscripts as “of David.”

Thirteen of these superscriptions also refer to historical events in David’s life (Pss. 3, 7, 18, 34, 51, 52, 54, 56, 57, 59, 60, 63, 142), suggesting these psalms could be read as composed by him on these occasions. This hypothesis, however, is at variance with the observations above that psalms have been composed generically—from the outset—for typical, recurring human needs and services of worship. In fact, many of these “Davidic” psalms mention developments that took place after David’s lifetime, such as the construction of the temple (5:7; 68:69; 138:2) and its courts (65:4), though it is possible these expressions are simply editorial updates of earlier psalms. Some of the historical superscriptions seem to be at variance with the contents of their psalms. The superscript to Psalm 63 points to David’s flight from Saul while “in the desert of Judah” (1 Sam 23–26), but the claim within the psalm that “the king will rejoice in God” seems out of place in reference to king Saul. The superscript of Psalm 59 is a citation of 1 Samuel 19:11, which narrates internal political intrigue, but the scope of the psalm itself is international where God is implored to “punish all the nations” and where the downfall of the enemies would make “known to the ends of the earth that God rules over Jacob.”

Further light on these psalms superscripts may be found by examining where and how the other technical terms are used elsewhere in the Bible. In each case they point to the postexilic period for the origins of the superscripts. The only other appearances of the term “director/overseer/supervisor” are Hab 3:19; 2 Chr 2:1, 17; 34:13. (Other forms of this Hebrew Piel verb occur only in 1–2 Chronicles and Ezra, all postexilic books.) Some of the technical musical terms, such as “alamoth” (Ps 46) and “sheminith” (Pss 6; 12), are found elsewhere only in 1 Chronicles (15:20–21). Indeed, some of the chief Levites, namely Heman, Asaph, and Ethan, named in other psalm superscripts (Pss 50; 73–83; 88; 89) are also referenced here (1 Chr 15:19; regarding Korah, see 2 Chr 20:19).

In this larger passage David institutes the singing of a psalm (16:8–36), which is actually a composite of three separate psalms of three different genres found in the Book of Psalms (105:1–15; 96:1–13; 106:1, 47–48). These psalms evidently originated after David’s lifetime, as the Chronicler removed anachronistic references to the Solomonic temple. He replaced “his sanctuary” and “into his courts” (Ps 96:6, 8) with the generic “his place” and “before him” (1 Chr 16:27, 29). And the citation of Psalm 106 includes verse 48, which is actually the doxology that closes Book IV of the Psalter and was thus added no earlier than the postexilic period. Close comparison of this wider narrative, in which David brings the ark of the covenant into Jerusalem (1 Chr 13–16), with its parallels in 2 Samuel shows that the Chronicler recasts the David of 1–2 Samuel as an exemplar of Jewish piety. Thus, as 1 Chronicles presents David as a model worshiper and a composer of psalms, so the psalm superscripts probably reflect the same mode of reinterpretation, as is probably the case for Psalm 51.

The probability that David’s deepening association with particular psalms was a postexilic phenomenon increases once we consider the LXX. It prefaces the equivalent phrase, “of David,” to 85 psalms (adding Pss 33, 43, 71, 91, 93–99, 104, and 137, though dropping Pss 122 and 124).

Once the Psalms became sacred literature and were incorporated with other scriptures in the exilic and postexilic periods, the psalms “of David” were probably correlated with the David of 1–2 Samuel. Some of these superscriptions thus invite readers to reinterpret them as psalms “by” David. Since he was “a man after God’s own heart” (1 Sam. 13:14; Acts 13:22), his prayers became exemplary prayers for the people of God. Thus, Davidic authorship of psalms is indeed biblical, so long as it is recognized that this forms a reinterpretation of liturgical psalmody, in order to personalize and embody the pious Jew loyal to God.

Whether or not David was their author, the psalms were preserved, not to give us historical information about David, but to serve as models of prayer and praise for the people of God. It is as open-ended poetry that the Psalms have retained their universal appeal over the millennia, making them suitable to any worshiper at any time and from any place.

The Genres and Life Settings of the Psalms

As most psalms were originally designed for the regular worship services, especially at the Jerusalem temple, our best path for surveying the various genres or types of psalms would be to imagine the path that pilgrims would have followed in the performance of psalms. We should begin with pilgrim psalms that reflect the journeys both to and from the temple. Once we arrive at the temple we must participate in the rite of passage, the liturgies that clarify who may enter this sacred space. Then we would engage in the singing of hymns appropriate to the annual festivals of Passover, Weeks, and Tabernacles, including the “songs of Zion” and the psalms of Yahweh’s kingship.

As noted above, the book of Psalms also contains special prayers and thanksgivings for particular groups and needs. As prayer psalms of the individual reflect little connection to a sacred site and its rituals, they were probably performed wherever needed. But once such prayer psalms were answered, their corresponding psalms of thanksgiving would have been performed before a congregation, where this public testimony could have taken place. In cases of national emergencies, such as an impending battle, royal psalms on behalf of the king and his army would have been offered at the Jerusalem temple, as would royal psalms commemorating the enthronement of the king’s successor.

Pilgrim Psalms

► Pilgrim psalms initiated the journey to the temple during the three annual festivals.

A prophetic oracle of hope contained in the book of Isaiah discloses the function of song both during the journey to and the observance of a pilgrim festival: “You shall have a song as in the night when a holy festival is kept; and gladness of heart, as when one sets out to the sound of the flute to go to the mountain of the Lord, to the Rock of Israel” (Isa 30:29). Some psalms of the individual are particularly suited for pilgrims: Pss 23; 27 (possibly); 42–43; 61; 63; 84. The “Psalms of Ascents” (Pss 120–134), especially Psalms 121 and 122, appear to be a collection designed especially for pilgrims visiting the Second Temple. The psalms reflect on the journey to temple, to which Yahweh gathers His people within His protective sanctuary (see esp. Pss 23 and 61).

Temple Entry Liturgies

► Temple entry psalms reflect the rites of entering sacred space: the righteous may enter and enjoy the benefits of entering God’s presence and the wicked may not and so will perish.

Psalms 15 and 24 (esp. Ps 24:3–6), along with Isaiah 33:14b–16, contain (a) a double question of who may sojourn on Yahweh’s holy hill, (b) a reply listing qualifications, and (c) a promise for those who enter. As the longer list of qualifications in Psalm 15 may be counted as 10, so these psalms appear to be a form of priestly-prophetic “torah” proclaimed to the assembled pilgrims. Psalm 24 locates its entry “torah” within the context of the entry of “the King of Glory,” whose presence was probably symbolized by the cherubim-ark, through the sacred “gates.”

While most commentators have assigned Psalms 5, 26, 28, 36, and 52 to various genres, mostly individual laments, none of them actually contains a formal lament. Their reference to the wicked mentions no threat to the speaker, nor lament for victims. As the description of the “righteous” in Psalms 15 and 24 does not identify a particular person, so the descriptions of the “wicked” in Psalms 5, 26, 28, 36, and 52 do not report on particular persons or social groups in ancient Israel. Rather, these descriptions are simply character profiles, focusing on deceitful speech. As in the case of most psalms, the language here derives primarily from the symbolism and metaphors of the temple, not from personal or social circumstances.

Each of these psalms shows affinities to the temple entry liturgies contained in Psalms 15 and 24, where there are indications of judgment and the parting of the ways—the “righteous” who may enter and the “wicked” who may not. These psalms also appear to locate their performance at the temple, and the “I” in these psalms appears to speak on behalf of other worshipers. Hence, these psalms were probably used as a form of a congregational response to the temple entry torahs proclaimed by the priests.

These temple entry liturgies underscore the momentous moment of meeting with God, as the pilgrims seek to enter His holy/sacred space. The worshiper’s character must be appropriate to the character of the God they claim to worship. The litmus test God employs to determine the true color of His worshipers is dipped into their daily, public lives, not the private corners of “spirituality” or of their “personal” relationship with God. How they treat their neighbors Yahweh considers symptomatic of the inner life. There is neither mere ritualism or privatized piety. Behind claims to spirituality, there must be concrete social behaviors. The psalms thus share with the biblical Prophets the notion that social justice is a prerequisite for authentic worship.

Corporate Hymns

► Corporate hymns were performed by Levitical choirs, in song and ritual, at the major festivals. They extol God’s attributes and deeds in a general or summary fashion.

Once the pilgrims were ritually admitted into the sacred space of the temple, they could participate in the worship led by the Levitical choirs as they sang the hymnic praises (tehillah), which extol God’s attributes and deeds in a general or summary fashion. So Psalm 145 acclaims His “mighty acts” generally as “great” and “good,” while Psalm 136 narrates particular events of the exodus deliverance. The psalms generally regarded as hymns are Psalms 8, 29, 33, 65, 66, 68, 75 (also combining elements of thanksgiving and prophecy), 78 (though explicitly “teaching”), 81, 92 (with elements of individual thanksgiving), 95, 100, 103, 104, 105, 107 (though a form of corporate thanksgiving), 111 (with elements of thanksgiving and wisdom psalms), 113, 114, 115 (with elements of corporate prayer), 117, 118 (with elements of individual thanksgiving), 135, 136, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150. Some of these hymns also contain prophetic oracles (75:2–5; 81:6–16; 95:8–11). Most begin with an imperatival call to praise, invoking the congregation to “sing,” “give thanks,” and “praise” (especially with the familiar, “Hallelu-Yah,” i.e., “Praise [pl.] the Lord”), and often followed with an introductory summary (e.g., “for he is good”). The body of the Psalm extols God’s greatness and goodness.

Some hymns were evidently performed to accompany temple rituals. Psalm 68, for example, describes Yahweh’s “procession” into “the sanctuary” as a concurrent event (Ps 68:24). It opens with the “song of the ark” (cf. Num 10:35), which Moses had sung at the beginning of each day as the ark led the people through the wilderness. As this song invokes God to “arise,” we should imagine this imperative initiates a procession led by the cherubim-ark, which symbolized both Yahweh’s throne and chariot, as it “ascended” into the sanctuary. This ritual procession recalls Yahweh’s “march through the wilderness” (Ps 68:7) as He journeyed from His sacred mountain of “Sinai” and finally “ascended” into “his sanctuary” (Ps 68:17–18) now in “Jerusalem” (Ps 68:29). Yahweh “rides” the “clouds” (Ps 68:4) and “the skies/heavens” (Ps 68:33) on this cherubim-chariot (Ps 68:17, cf. 18:10; 104:3–4) as the God of the skies who “thunders” above, “blows” His enemies away, and “pours down rain” for His land and people (Ps 68:2, 7–10, 33). The several closing references to Yahweh’s “power” (Ps 68:28, 33–35) make sense in light of the designation “the ark of your power” in Psalm 132:7–8 (so also in Ps 78:61). It is otherwise difficult, if not impossible, to explain the unity and development of Psalm 68 apart from this connection to the ritual procession of the cherubim-ark.

Some hymns reflect affinities to particular pilgrim festivals. Psalm 66 commemorates when Yahweh “turned the sea into dry land” (Ps 66:6) and so connects with the Passover festival. Its structure also illustrates how individual thanksgiving and the thanksgiving sacrifices were incorporated into the worship at this festival. Psalm 65 mentions the fulfillment of vows, hints at the partaking of thanksgiving offerings (Ps 65:1, 4), and celebrates the rains that God has brought, while there is yet grain in the fields (Ps 65:9–13). These clues point to the Feast of Unleavened Bread (also known as Passover), at the time of the barley harvest but seven weeks before the wheat harvest (as noted in the Hebrew inscription, the Gezer Calendar; cf. also “the sheaf of the firstfruits of your harvest,” i.e., barley in Lev 23:4–16).

Songs of Zion

► Songs of Zion celebrate the sacrament of Yahweh’s dwelling on his sacred mountain.

Psalms 46; 48; 76; 84; 87 (note also 132:13–18) are called songs of Zion (so named in 137:3). Mount Zion was the hill on which the Solomonic temple was built. While most hymns call the congregation to celebrate Yahweh’s character and deeds, these songs focus on Yahweh special relationship to His sacred mountain (46:4; 48:1; 87:1). Psalms 46, 48, and 76 confess that “God is … in Zion,” report that God has stilled the nations who assail it, and enjoin worshipers to acknowledge God as sovereign protector. Nations are also mentioned in Psalm 87, but here they come, not as aggressors, but as Yahweh’s pilgrims who may claim their birthright in Zion. Unusual as this may sound, other psalms refer to international participants in the worship of Yahweh (47:9; 96:7–9; 100:1).

Psalms of Yahweh’s Kingship

► The psalms of Yahweh’s kingship echo the plot line of the God of the skies and reflect the ritual ascent of the cherubim-ark into the (cosmic) temple.

Most scholars assign Psalms 47; 93; 96; 97; 98; 99 to the genre of the psalms of Yahweh’s kingship. The psalms tend to be more international and cosmic in scope, with less emphasis on Israel’s special position. With the exception of Psalm 98, each contains the acclamation, “the Lord reigns” (Yhwh mlk). In most cases where a proper name immediately precedes this Hebrew verb, the phrase carries the meaning, “so-and-so has become king!” (1 Kgs 1:18; 15:25; 16:29; 22:41, 51; 2 Kgs 3:1; 15:13). Strange as it might sound, these psalms celebrate Yahweh’s kingship by liturgically reenacting His “enthronement.” They do not suggest that at some prior time Yahweh was not king. They are analogous to the Easter hymn, “Christ the Lord Is Risen Today.” Rather than implying that Jesus is resurrected each year, this hymn celebrates Christ’s resurrection by contemporizing this event with the moment of worship.

Prominent in these psalms is the symbolism of the cherubim-ark, whereby Yahweh is portrayed as enthroned and also riding this chariot. Echoed here is the wider ancient Near Eastern tradition of cosmic divine kingship, whereby (a) the deity of the skies prevails over the chaotic waters, (b) is thereby acclaimed king, (c) whose temple/palace is constructed on His sacred mountain (see esp. Psalms 93 and 97).

Individual Prayer Psalms

► As individual prayers exhibit little connection to the national sanctuary and its traditions, they were likely performed by a village elder/Levite. The three subjects of the lament seek to evoke a response from “my God,” who should answer when called upon.

The individual prayers are Psalms 3; 4; 6; 7; 13; 17; 22; 25; 27; 31; 35; 38; 39; 40; 41; 42–43; 51; 54; 55; 56; 57; 59; 61; 64; 69; 70; 71; 77; 86; 88; 102; 109; 139; 140; 141; 142; 143. In some individual prayers the speaking “I” appears to be a representative liturgist leading a regular service, not a lone individual in special crisis (perhaps Pss 4; 25; 40; 57; 61; 64; 139). Some individual prayers reflect corporate concerns, such as social unrest (Pss 59; 64; 140) and the exile (Pss 77; 102), and thus perhaps corporate usage. The psalms of trust are Pss. 11; 16; 23; 62; 63; 91.

Unlike the psalmic genres described thus far, the prayer psalms of the individual lack clear links to a sanctuary, congregation, and rituals. While they may on occasion refer to Yahweh’s sacred space (e.g., 3:4), they gave no indications that they were actually performed there, in contrast to the hymns and psalms of temple entry. They were probably used in less official, more private ceremonies, overseen by a liturgist, Levite, or elder, on the occasion of an individual’s special emergency. Especially in cases of sickness (e.g., Ps 38), it is more reasonable to assume that the psalm was invoked over the individual’s sickbed, rather requiring the individual be transported to a sanctuary in order to enjoy the benefits of a prayer psalm.

Not surprisingly, these psalms also lack allusions to the national, historical traditions recorded in the hymns and corporate prayer psalms. Instead they reflect a simpler piety: a belief in “my God” who will answer when the petitioner calls.

1. Address and introductory petition

“O Lord” (13:1)

“Be gracious to me and hear my prayer” (4:1)

2. Lament

a. I (speaker)

“How long must I put anxieties in my soul?” (13:2)

b. You (God)

“How long . . . ? Will you forget me forever?” (13:1)

c. They (foe)

“How long will my enemy be exalted over me?” (13:2)

3. Confession of trust

“But I in your loyalty have trusted” (13:5)

4. Petition

a. For favor

“Look, answer me” (13:3)

b. For intervention

“Give light to my eyes” (13:3)

c. Motive

“lest my enemy say, ‘I have prevailed over him,’” 13:4)

5. Vow of praise

“I will sing to the Lord” (13:6)

6. Thanksgiving in anticipation

“for he has acted on my behalf” (13:6)

In the lament the distress is described in a way to evoke a response from Yahweh. Generally the I-lament should evoke His pity, the God-lament His sense of obligation to help, and the foe-lament His anger. Only a third of all prayer psalms (including individual and corporate) contain a lament against God, concerning His disposition (e.g., his wrath, forgetting, or hiding his face) or (non-) intervention, whether actively hostile (e.g., 89:42) or passively indifferent (e.g., 10:1). Among the prayer psalms we may distinguish between psalms of plea, where God is third-party to the distress, and psalms of complaint, where He is alleged to bear some responsibility.

Corporate Prayer Psalms

► Corporate prayers reflect national crises and draw from national traditions to form an argument to persuade God.

The corporate prayers are Psalms 9–10; 12; 14; 44; 53; 58; 60; 67; 74; 79; 80; 82; 83; 85; 89 (also a royal psalm); 90; 94; 106; 108; 137; 144 (with royal adaptations). Their literary motifs are very similar to those of the individual prayers. But instead of the “confession of trust” there is often a “reference to past saving deeds,” which recalls corporate, historical traditions. In addition, the “vow of praise” does not appear to be an essential component, as in the individual prayers.

The corporate prayer psalms tend to be longer and contain a more sustained argument for Yahweh’s intervention, based on His earlier praiseworthy acts known from prior tradition. In some cases, the psalm juxtaposes these earlier praise traditions with the lamentable experience of the congregation, which is described as a reversal of the prior precedent of salvation (see esp. Pss 44; 89).

Individual Thanksgivings

► Individual thanksgivings commemorate God’s answer to a prior individual prayer in a congregational setting

The thanksgiving psalms are Psalms 30; 32; 34; 116; 138 (see also 40:1–10; 66:13–20; 118: 5–18, 21, 28). While the psalmic hymns (tehillah) extol God’s attributes and deeds in general or summary fashion, the individual thanksgivings (todah) praise Him for a single, recent deliverance. They generally contain these motifs.

1. Proclamation of praise

“I exalt you, O Lord” (Ps 30:1a)

2. Introductory summary

“for you lifted me out of the depths” (Ps 30:1)

3. Report of deliverance

a. Recounting the lament

“when you hid your face, I was dismayed” (Ps 30:6–7)

b. Recounting the petition

“To you O Lord, I called” (Ps 30:8–10, and 30:2)

c. Recounting God’s response and deliverance

“You turned my wailing into dancing” (Ps 30:11, and 30:3)

4. Renewed vow of praise

“I will give you thanks forever” (Ps 30:12)

5. Hymnic praise

“Sing to the Lord . . . for his anger lasts only a moment” (Ps 30:4–5)

The individual thanksgivings form the flip side of the individual prayers, forming the praise vowed at the end of the prayer psalms. The “report of deliverance” is essentially a testimony and is largely a rehearsal of the earlier prayer. As these thanksgivings address a congregation (Ps 30:4; 116:14, 18–19; cf. 22:22, 25), they were likely performed in a formal, public ceremony, perhaps at the temple. In most cases, accompanying the performance of a thanksgiving psalm there would be a thanksgiving sacrifice (Ps 116:17–19).

Royal Psalms

►Royal psalms prescribe the ideals of Davidic kingship. They underwent a prophetic reinterpretation, encouraging expectations of new David/messiah.

The royal psalms are Pss. 2; 18; 20; 21; 45; 72; 89 (also a corporate prayer); 101 (though perhaps related to temple entry); 110; 144 (though probably a composite applied to the postexilic community) (note also 132:1–12). Although the Davidic king is central to each, these psalms do not form a literary genre per se, as they contain a variety of literary motifs and reflect a variety of social functions, such as coronations (Pss 2; 110), weddings (Ps 45), prayers before and after battles (Pss 18; 20; 21; 89), and general intercessions (Ps 72).

While the Royal psalms come to have messianic significance in the New Testament, they were originally sung on behalf of the Davidic kings in the pre-exilic period. They reflect the prescribed ideals of the monarchy, such as a reign characterized by righteousness and justice and by victory and an extensive empire. The historical books of 1–2 Kings, however, reflect the described realities of the monarchy and tell of its ultimate failure to reach these ideals. In Psalm 89, for example, the dynastic oracle promises the king a claim to divine sonship and to supremacy over earthly kings (Ps 89:26–27), but the later lament describes the king’s miserable failure in battle (Ps 89:49).

So if the Davidic monarchy ended in failure with the Babylonian exile, why were the Royal psalms retained in the Book of Psalms, which was finalized in the postexilic period—when Judah had no king of their own under the Persian Empire? Their retention is best explained by their reinterpretation exemplified in the Prophets, who took up the language of these royal psalms and engendered the hope for a new David (e.g., Isa. 9:6–7; 11:1–5; Mic. 5:2–5a; Jer. 23:5–6; Ezek. 34:23–24; 37:24–28; Zech. 9:9–10). Thus, even before the New Testament these psalms took on prophetic significance.

The New Testament then begins with the claim that “Jesus Christ” is “the son of David” (Matt 1:1) and takes a prophetic interpretation of psalms one step further. After the appearance of Jesus Christ, the Psalms were seen in a new light. Not only was He identified as “son of David” (Matt 1:1; 21:9, 15; 22:41–45), He was also “son of man” (Ps 8:4 and Heb 2:6–10), that is, He was both anointed king and supremely human. As the embodiment of the true Israel and of the Davidic persona in the psalms (see the sidebar, “David and the Psalms Superscripts”), even laments such as, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” and “they divide my garments among them, and for my clothing they cast lots” (Ps 22:1, 18), can foreshadow the passion of the Lamenter par excellence (Matt. 27:46; Mark 15:34; and John 19:24; Matt. 27:35; Luke 23:34).

Wisdom and Torah Psalms

► Wisdom psalms echo wisdom themes (as in Proverbs). Torah psalms celebrate Pentateuchal precepts.

Wisdom psalms reflect the same wisdom tradition known from Proverbs, Job, and Ecclesiastes. Rather than addressing God directly in worship, they incorporate literary forms characteristic of the wise sages and either teach wise living or probe life’s anomalies. Psalm 37, for example, concerns the problem of the prosperity of the wicked and forms an acrostic, where the first word of each verse follows the Hebrew alphabet (as in the poem of the valiant wife closing the book of Proverbs, 31:10–31), and contains the “better than” proverbial form (cf. Ps 37:16 and Prov. 15:16; 16:8). Similarly, Psalm 49 probes the folly and fatal end of those who trust in their wealth and refers to literary forms such as the proverb and riddle. Psalm 112, another acrostic, celebrates the virtues and rewards of the righteous.

The Torah psalms, Psalms 1, 19:7–19, and 119, uniquely refer to “the law of the Lord.” While “torah” is usually translated “law,” the word means “instruction,” and thus can include instruction of any form, such as laws, narratives, and poems. Because Psalms 19 and 119 also refer to the Lord’s “testimonies,” “precepts, “commandments,” and “judgments,” the particular torah to which they refer is the Torah of the Pentateuch. These psalms testify to a dramatic shift in Israel’s faith: from the liturgies and rituals of the temple as the primary locus of devotion in the pre-exilic period to written Torah in the postexilic period.

The Theology and Spirituality of the Psalms

►The psalms were human poems hammered out over generations of experience with God. As such they “mirror” their theology.

It may be no accident that the Book of Psalms appears in the center of the Christian Bible. The Psalms express the heart and soul of the conversation that takes place between God and His people. Its popularity through the millennia lies in its human words that articulate our innermost joys, aspirations, and fears and in its prophetic words in which God Himself assures us and unmasks our pretensions.

The Psalms are not merely ancient liturgies and literature for the curious. As Scripture, the Psalms disclose God. This is ironic because, unlike Mosaic Torah and the Prophets, the Psalms are primarily human words addressed to God. Yet as prayers and praises to God hammered out over generations of experience with God, they reflect what Israel found to be appropriate and effective speech to God. In this respect, they are not a “lens” focused on God, as the Prophets represent, rather they are a “mirror” reflecting the character of God.

For example, time and again the psalms refer to “the face of God” (24:6; 27:4, 8; 105:4) and petition Him to “incline your ear” (17:6; 102:2) and to “see my affliction” (9:13; cf. 33:18). These claims are remarkable—especially considering they could have been misconstrued in the cultural context of ancient Israel. Among Israel’s neighbors “the face of God” was understood to have its literal counterpart in the face of a divine statue or idol. So the biblical Psalms, at the risk of people misinterpreting “God’s face” and thus violating the Bible’s repeated prohibition against images, nonetheless insist on using this metaphor to portray God as a living, interacting person.

For another example we should observe the lament or prayer psalms. Their laments attempt to move God to pity and their petitions implore Him to intervene. Together these motifs testify to the belief that God can be persuaded. Thus, indirectly, the Psalms makes a profound statement on the sovereign condescension of God, whereby He chooses to open Himself to human influence.

► The Israelites sought a royal audience at Yahweh's palace and brought him tribute with their hymnic praises and ritual sacrifices.

In addition to being a source for theology, the Psalms urge God’s people to engage those beliefs in worship. For the Christian the Psalms are not only Scripture; they are also a hymnbook. The Apostle Paul enjoins believers to “address one another with psalms and hymns and spiritual songs” (Eph 5:19; Col 3:16). The Psalms should not only inform beliefs about God, humans, and the world; they should also shape worship. The lament psalms invite God’s people into a world where they may “pour out” their “heart before him” (cf. Ps 62:8)—in terms that authentically disclose the heart, even if those laments are not always “theologically correct” (e.g., compare Ps 22:1 and 22:24). And the liturgies of temple entry and the hymns invite God’s people into the palace to have an audience with the cosmic King (Pss 24; 95).

As the prophet Hosea enjoins the people of Israel, “Take with you words and return to the Lord” (Hos 14:2), so the Book of Psalms provides such words for God’s people to beseech and worship the Lord.